TV audiences in the late nineties stood witness as an aspiring comedian rose to fame in Japan… unwittingly, that is.

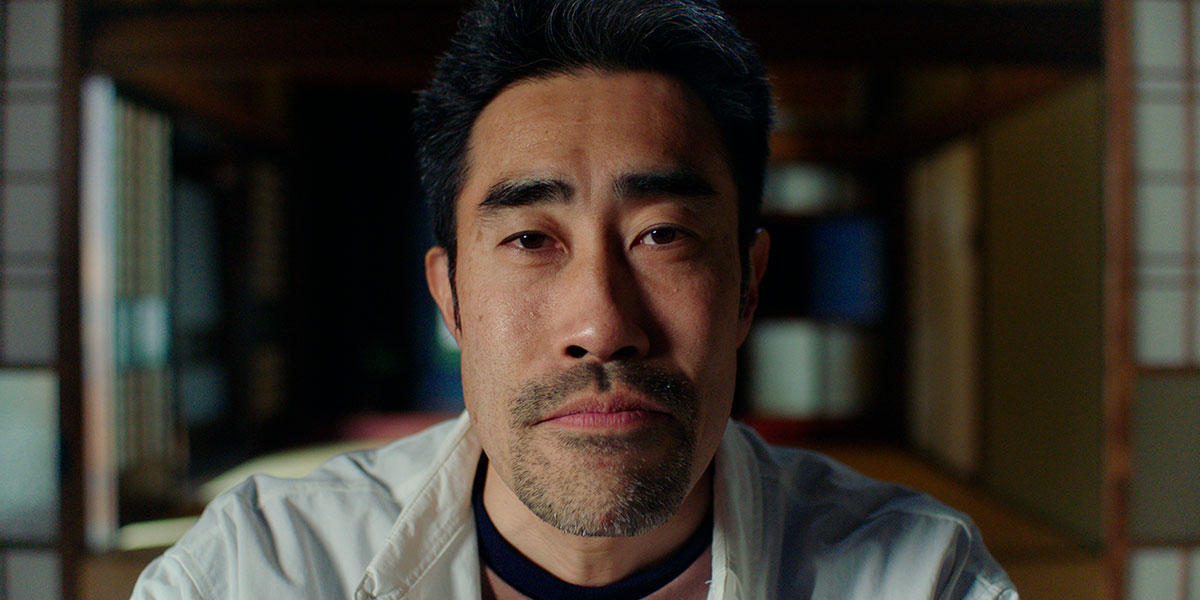

Clair Titley’s feature directorial debut, The Contestant, attempts to rectify these initial, and no doubt, traumatizing conditions of celebrity for Tomoaki Hamatsu who rose to fame by appearing on the eccentric game show Denpa Shōnen: A Life in Prizes, through directorial choices involving rigorous and rolling practices of informed consent. Now a television personality better known by his nickname, Nasubi — meaning “eggplant” in reference to his long face – the star is ready to look back at the show that made him famous. The Contestant opens this year’s DOC NYC festival after premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in September.

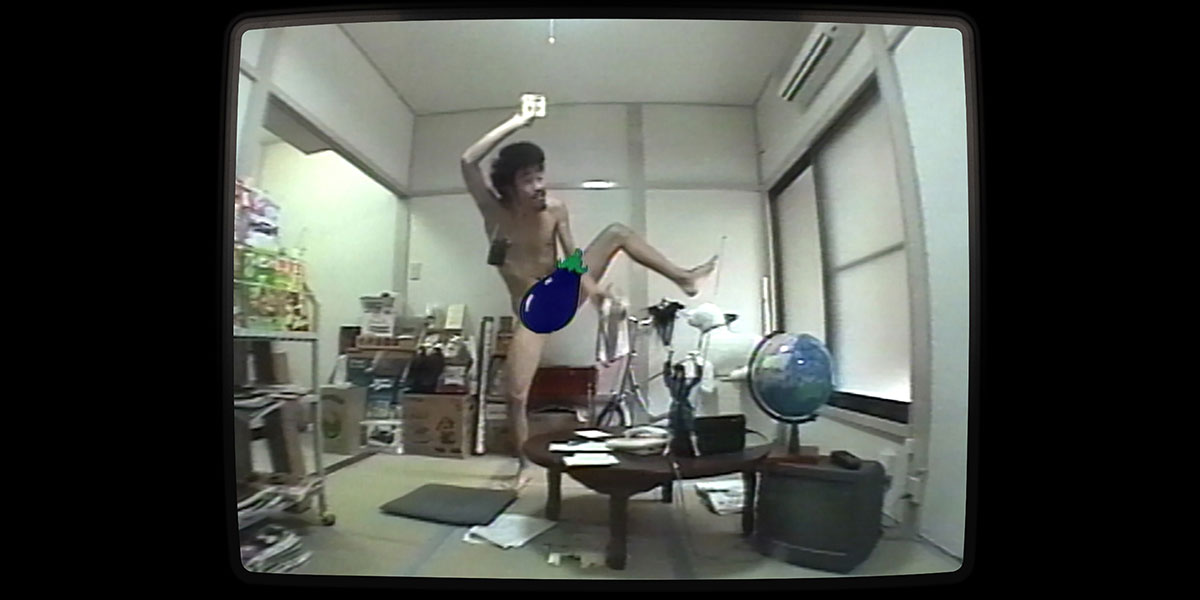

Over the course of 15 months in 1998, Nasubi became a household name after renowned TV producer Toshio Tsuchiya enlisted him in a simple, but outrageous challenge. Its premise? Nasubi was to stay naked in an apartment, filling out magazine sweepstakes to win what he needed to survive — namely, food, clothing, and appliances — until he reached the prize goal of one million yen. Aside from occasional check-ins with Tsuchiya, the contestant was cut off from all contact with his family and the world –– a setup likened to that of solitary confinement. While Nasubi was told he could have left at any point in time, what he wasn’t told was that his experience was also being broadcast on TV. To over 15 million people.

Through interviews with Nasubi, Tsuchiya, and those peripheral to their lives, The Contestant digs deep into the psyche of people who search for connection in whatever way they know how, the aftermath of being exploited for entertainment, and, most importantly, what it means to heal from being known without having a say in the matter.

POV spoke with Titley about the doc following the TIFF premiere of The Contestant.

POV: Audrey Chan

CT: Clair Titley

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Note: The following article contains mentions of suicide.

POV: How did you decide to make a doc about this subject matter?

CT: I was researching another documentary on the Internet and went down one of those rabbit holes where you get lost and go, “This is a crazy story.” I couldn’t get my head around how [Nasubi] had stayed in there and why he didn’t leave. We started a conversation with some online letters back and forth. Eventually, he came over to the UK for a holiday. I couldn’t afford to go over to do a taster tape, so he said, “I’m coming to you.” We had this crazy holiday in the UK on the seaside with my family, the interpreter –– who lives down the road with her family –– and Nasubi, who doesn’t speak any English. I don’t really speak any Japanese. We got to know each other by playing ping pong in the evenings and [taking] long car journeys. I make it sound like it happened quickly, but this has been a long time. We’ve been talking for years.

POV: The production took seven years, more or less?

CT: Pretty much. The beginning is always really slow, then there are pauses and breaks. But it’s been going on for around that amount of time, on and off.

POV: Did anything unplanned happen during filming that surprised you? Seven years is a long time.

CT: COVID got in the way. That was a major thing for us because we were due to be filming in Japan. I’d worked very closely with Megumi Inman, who’s my Japanese producer. We always had a plan that she would be the face of the interviews for the Japanese speakers because we both believe that you need to look somebody in the eyes when you talk to them. I don’t speak the language, but all of a sudden, I wasn’t even able to be in the country. I had to do all the shoots remotely. Meg also had to do two weeks of quarantine in a hotel room. It was quite meta because she was trapped in a hotel where they’d knock on the door and leave her food outside –– it was really strict in Japan. So, not only did I do the whole shoot on Japanese time, but I worked with her during her quarantine on Japanese time as well. I was awake during the night and we would talk through the project, the themes, and the interviews. By the time the interviews came along, I was fully on Japan time even though I was in the UK, in the back of the bedroom or in the shed in the garden, which is where I did all the interviews. It was bizarre. My little girl would come home from school at about half past three in the afternoon, and she’d tuck me into bed and say goodnight. I’d wake up and start my day at midnight. That was probably the biggest obstacle we faced.

POV: How did you go about gaining access to all the unaired footage?

CT: The other producer, Andee Ryder, worked such amazing miracles with that. The negotiations took a long time because we were doing it between Japan, the UK, and our financiers –– they’re in the US. Even trying to talk to each other was hard. One of the key people in that whole negotiation process was actually Toshio Tsuchiya. Without him, I don’t know that we would have been as successful. He was brilliant at greasing the wheels and making sure we knew the right people to talk to. He put in a good word for us. Because people knew he was on board with the project, they were happy for us to have the archive.

POV: On that note, with Tsuchiya being willing to work with you on this project –– Thom Powers recently pointed out how your doc urges filmmakers to rethink the power dynamics they share with their subjects. Was this something on your mind during production?

CT: Consent has been a massive part of this [project] from the beginning and that’s because I’ve checked in with Nasubi at every point. I’ve made sure that he understands what’s happening. We’ve talked about [the film] being a collaborative process, and while he doesn’t have editorial control over it, we have been very open and honest –– both with him and Tsuchiya. Both of them were allowed to see cuts of the film and we listened to what they had to say. Sometimes we took things on board and sometimes we didn’t. It’s a rolling process. Consent is something that you keep addressing. I think that’s why everybody was happy about it –– because we’ve been very open from the start. We didn’t go in, do an interview with everybody then run away, produce, and show them the finished . We kept in contact.

POV: What sort of aftercare do you have in place for Nasubi, now that the doc has premiered?

CT: We keep the conversation going. He has access to therapy. We’ve talked in depth about the kinds of therapy they have in Japan, as it can be quite clinical. Not all of it, but talking therapy is not as much of a thing as it is necessarily in the UK and the US. But he has access to all of that whenever he wants it. He has access to us for support as well, helping him to navigate whatever issues might come up from a mental health point of view.

POV: You’ve noted that your doc is more of an exploration of Nasubi as a person rather than a critique of Japanese pop culture and its values. How did you make that distinction clear as you approached and made the film?

CT: I’ve been very conscious of the fact that I’m a Western woman making a film about a Japanese man. I’m very aware of how, in the past, Western media has been very quick to make judgments or stereotypes sometimes. I’ve seen it myself. There were a couple of things I really didn’t want to do. Number one: I didn’t want to have a ‘voice of God’ –– I didn’t want to have a Western storyteller telling you what to think either about reality TV about Nasubi or about Japanese culture. We do have Juliet in the film –– the BBC journalist –– and I was even cautious about incorporating Juliet, although she’s very much integral to the story. She’s embedded and part of it because she was there at the time. She was the first and only journalist to ask him questions when he was at what they called ‘The Naked Festival’ –– the finale. But we were very cautious not to make these sweeping generalizations.

POV: Your film has been described as an exploration into today’s culture of oversharing. Why is now a good time to release this film? Why revisit something that aired over 20 years ago at this moment today?

CT: This film constantly feels like it’s [made for] the right time. Just after COVID, it felt right because it was all about isolation and connecting with the world. At least in the UK, there have been horrific things –– people committing suicide in the past few years, and I’m sure it’s happened in the US and Japan as well, with Terrace House. [A Japanese reality TV series that sparked controversy when star Hana Kimura died in a suicide in 2020 following online bullying from fans.] With those themes, it feels like an appropriate time. What I really love about this film is that it’s about a man looking for connection in the wrong places to start. Everybody who watches it gets something else out of it –– something relevant to them. People come out being really passionate that it’s a film all about consent. Somebody else came out and said, “It’s all about the power of the media and how it has too much power, and that we need to respect boundaries.” Somebody from a social media generation will think this film is more about oversharing than you and I. You can say this about a lot of films, but particularly with this one, I feel that everybody puts their own agenda on it in a wonderful way. It sparks so much debate.

POV: I really liked the split screen near the beginning of the doc. What was your favourite stylistic decision you made that you think contributed to telling Nasubi’s story?

CT: That split screen was brilliant –– that’s Rachel Meyrick, the editor. We actually first did that later on in the film, when they’re having that conversation debating whether or not Nasubi is going to stay in Korea and Tsuchiya is trying to persuade him. We were trying to work out how to tell that and she came up with this brilliant way of doing it. So we tried to replicate it further earlier in the film, and that’s how that came about.

But the most important one was the way in which we translated all the archives from Japanese into English. I’m feeling a massive sense of relief now that it’s worked. At the time, it was hard to describe to everybody because when you’d show people rough cuts it would look so messy, and I’d be like, “Honest, it’s gonna look great!” That was important –– to be able to show people who don’t speak Japanese, to give them a sense of how overwhelming it was, and to understand the footage in front of them. Because if you just saw Japanese text and heard Japanese, after a while, I think you’d zone out because it’s an onslaught for the senses. You can’t access it, whereas this allows us to really be able to be absorbed in it. The flip side of that is we also removed a lot of the graphics, audio, and canned laughter –– all of those sound effects. Because we didn’t have those rushes, those dailies –– we just had what was screened, and it was covered in all this cartoon writing and these noises –– by removing all of that, we could show people what it was like for him to be in the room all by himself.