What do food and books have in common? They’re both enjoyable to digest and each one attracts both critics and die-hard enthusiasts. But follow closely the trickle of sweat down the brow of a chef who must execute the quintessential menu, or a craftsman who binds the work of the world’s most celebrated visual artists, and you’ll see similarities that surface in the name of perfectionism.

Astuteness to this degree often means looking at the materials at hand as something entirely outside its form. It’s not only about the taste, but the sound, shape, colour and architecture of food, just as a book is not complete without its format, weight, texture and smell. Gereon Wetzel’s two films, El Bulli: Cooking in Progress and How to Make a Book with Steidl, deal with the whole experience–-the total work of art–-or as they say in German, the Gesamtkunstwerk.

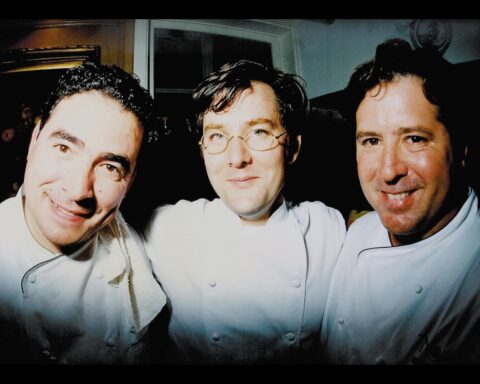

Observing his two protagonists—Ferran Adrià, creator of El Bulli, the world’s most extravagant 3-star restaurant, and acclaimed art book publisher Gerhard Steidl—as they tackle painstaking details, rumble with their colleagues and hurtle over the roadblocks in their realities, Wetzel assembles two original portraits that overlap where the precision and passion of these pros is concerned.

“I am interested in finding a process where you can really see how a craft works and where the decisions come from,” says Wetzel. “It’s not about the status of a craftsman, but rather a process where these crafts, or a certain way of thinking, can come out. That said, I think the two films are very similar because both of them look at what is actually happening.”

Food as Form

El Bulli is located in Roses, Spain, overlooking the Cala Montjoi bay in the northwest region of Catalonia. Ferran Adrià has been dubbed the greatest chef in the world, pushing the boundaries of what constitutes as food while toying with the chemistry of taste. Infamous for its controversial experimentation with molecular gastronomy (often using nitrogen to turn food into new forms), El Bulli holds a reputation as an avant-garde restaurant where the experience of fine dining becomes an exploration of the senses and the venue itself a museum of precious works of art. It’s no longer ‘food’ that is being digested, but rather ornate objects.

Each year, the restaurant closes for six months to allow for a select team of top chefs to design the restaurant’s new menu for the coming season. Originally, Wetzel had planned to shoot the film five years ago, but due to Adrià’s demanding schedule, production had to be postponed. It was then that Wetzel “started with a new idea to show the cycle in Adrià’s work: a half year in the laboratory and a half year in the restaurant. And because this needed time, we waited until Ferran was ready to do the film with us.”

Wetzel’s careful camera moves through three stages in which Ferran Adrià and his fervent team explore the science of food. In an age where cooking shows have become increasingly trendy, what we see in El Bulli: Cooking in Progress is far beyond the cute creativity so popular among the cooking styles of Jamie Oliver and Nigella Lawson; or the high-pressured hysteria of the “all-stars” in the reality-TV program Top Chef; and even that raving arsehole Gordon Ramsay in Hell’s Kitchen.

Instead, Wetzel captures the methodical science of masterminds who transform a kitchen into an experimental laboratory, where every gadget and technological device is available to do all kinds of unimaginable things to food—‘vacuumizing’ seems to be among the most in demand, along with pressure-cooking and extracting juices and oils from food that appears dry and inert. Several moments arise when the chefs seriously debate whether the mushroom juice should be fried or left raw. How does one actually fry liquid? And can mushrooms even be juiced? Apparently so.

With sweet potatoes in vacuum-tight plastic bags, or exotic mushrooms peeled, sliced and arranged in decorative patterns that embody the delicacy of fish bones or fallen leaves, it’s possible to forget the substance at hand. As every new concoction is photographed and catalogued in a database, at times El Bulli’s ‘practice’ kitchen in Barcelona looks more like a crime laboratory. At other moments it resembles the operating room of the world’s most skilled surgeons, especially when the chefs are adorned in starched white coats.

Though sometimes the filmmaking is just as tedious as the preparation of the cuisine—certain moments seem to lag and drift and the tangent of some scenes loses focus—at its best, the film reflects the same process-based production mode as its subject matter. The first third is devoted to the ‘design laboratory’ (with very amusing bits of the chefs taking trips to the market, where at one point they buy only six grapes to dissect back at the lab); the second moves to the ‘rehearsal space’ where Adrià and the head chefs train the chefs, cooks, preps and servers to function in well-oiled assembly lines in the weeks prior to the restaurant’s opening; and in the final act, El Bulli opens its doors to a select group of auspicious patrons. By the restaurant’s account, El Bulli receives two million requests for reservations per year, but only accepts 8,000.

Such numbers, facts and figures are absent from Gereon Wetzel’s film, along with any direct interviews or information about the restaurant and its legend Ferran Adrià. “I don’t like interviews,” explains Wetzel. “You never find interviews in fictional films. Why? Because they’re boring and they only concentrate on the content, not on who the people are or what they do.”

As Wetzel puts it, he’s “not interested in describing a subject or its content, but rather following the people in front of the camera. I’m interested in everything that cannot be shown in a book or on a webpage.” Realizing they had ‘too many cooks in the kitchen’, Wetzel does double duty as director and soundman, working with two other crewmembers. The fly-on-the-wall technique melded perfectly into the background without shattering the concentration of the virtuosos at work. “We spent such a long time with them that they actually forgot about us,” says Wetzel.

Towards the end, there’s a remarkable scene where the camera holds on Adrià as he digests the entire menu, piece by piece, which is served to him by the head chef, Orilo. Adrià scribbles down notes and for each ‘plate of art’ offers his verbal commentary as he adjusts the order of tastes. And that’s how the 35-course menu is built: perfecting each dish based on feedback from the patrons, the critics and Adrià himself, likely the toughest of all. “It’s not about the single pieces but a composition of everything, and you can only understand it if you eat it all. Like the adagio in the middle of the symphony, you really have to hear it to understand the end.”

“First comes the magic, a new path with creativity, then comes the taste,” says Adrià to his staff. Indeed, El Bulli offers its guests a creative emotion when dining, as it pioneers not only how we taste food, but also how we interact with it. Sipping a cocktail topped with an oil slick offers both an intellectual and visceral experience: two textures, emotions and experiences, silk and liquid. And it is awe-inspiring when Adrià demonstrates praline ravioli whose pasta ‘vanishes’ when it’s dipped into pine water. Believe it or not, water and ice are actually the thematic ingredients of this particular El Bulli season, with such dishes as ice vinaigrette, an iced mint lake, and even water jelly! “It’s more like a symphony, this menu,” reflects Wetzel.

Wetzel recalls finally having the opportunity to sample El Bulli’s masterpieces.

“It was really very exciting because for three or four years we were occupied with this subject matter. And we ate nothing in the lab—we never tried a thing! Though I was also thinking, What do we do if it’s not good? But it was more than good, like everything that was promised in the film: excitement and dramaturgy.”