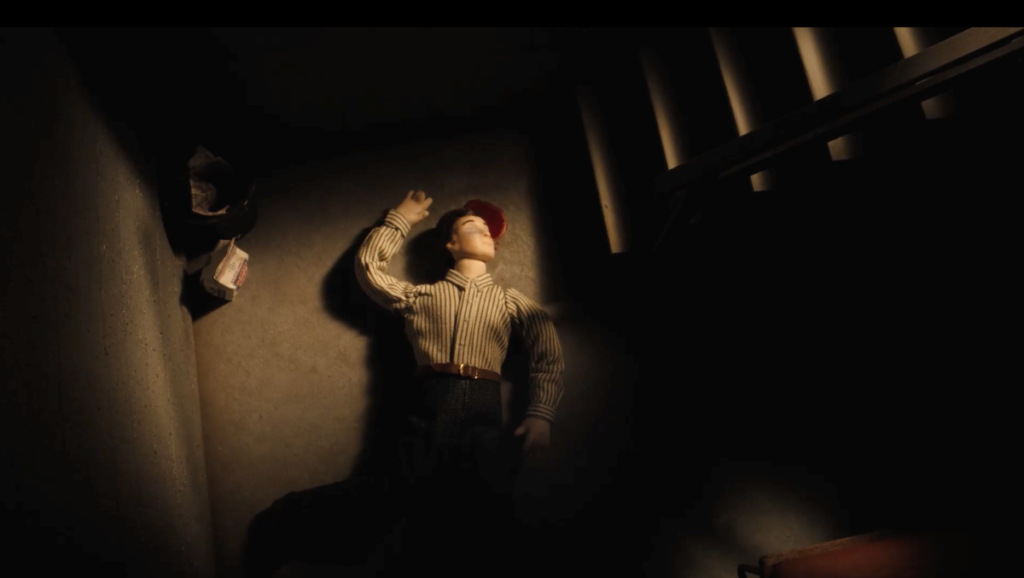

Somewhere in true crime heaven, Frances Glessner Lee is smiling. The pioneering miniaturist transformed a hobby into foundational work in forensic science. Her legacy informs much of Jackie Torrens’ wonderfully original documentary Bernie Langille Wants to Know What Happened to Bernie Langille. The film devises a world of miniature sets to recreate and investigate a truly bizarre case in 1968. As Langille’s grandson, also named Bernie, digs into the question of his grandfather’s strange death, which has been gnawing at the family for decades, Torrens draws upon Lee’s work in miniature to gain fresh perspective amid a Rashômon-like myriad of competing narratives, twists, and turns.

The story of Bernie Langille Wants to Know What Happened to Bernie Langille gets wilder by the minute. Bernie recounts how his grandmother awoke to discover her husband beside her in bed, covered in blood and with his skull cracked open. The case becomes stranger as the investigation yields more questions Langille and Torrens trace Bernie, Sr.’s odyssey that involves being assaulted by a doctor, getting hit by a train, and becoming the subject of an appalling military cover-up. The miniature world highlights the absurdity of it all. Amid the black humour of the premise and its twist-a-minute tale, however, the film excavates a traumatic past as the family hopes to heal.

POV spoke with Torrens by phone ahead of the world premiere of Bernie Langille Wants to Know What Happened to Bernie Langille at Hot Docs to discuss how she and her team created this unique world to explore the mystery, how trauma passes from generations, and how an artist protects her subject’s vulnerability in service of their story.

POV: Patrick Mullen

JT: Jackie Torrens

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: I understand you first met Bernie on Twitter. This film seems like one of the few positive things to come out of Twitter – how did that happen?

JT: He was asking the public for help, saying, “My grandfather died 15 years ago, and in a really unusual way. I’m just tweeting about this in case anybody out there might have any information that could help me and my family figure out exactly what happened.” I’m always on the hunt for stories and this got my attention immediately. I had been looking for a story in which to use this concept of telling documentary re-enactments through miniatures. I wanted to find a subversive story to play against how one might typically see miniatures, which are often associated with childhood, sometimes associated with femininity, or as a suitably feminine pursuit.

POV: Why true crime?

JT: I had done a documentary a few years before for CBC Radio on a group of miniature artists, and I was intrigued by the work of miniature artist Frances Glessner Lee, who did a series of dioramas called The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. She was born around the 1870s and she wanted to go into criminology. In those days, because she was a lady, they said, “Why don’t you take up a hobby instead?” She started making miniature dioramas that were based on real crime scenes. She eventually became a forensic scientist. In fact, she’s known as the mother of forensic science. Her dioramas are still used to train police officers.

POV: What was Bernie’s reaction to the idea of using the miniatures for the story?

JT: I think he thought they were very interesting. We originally did a short film because we knew the concept was unusual. To do a feature film we would need a sizable art department budget, which is not the usual for documentaries. The short was at Hot Docs in 2018. Bernie didn’t really understand how the miniatures would look until he saw the short. Members of his family who also saw the short started to comment the resemblance of what had actually happened in the Langille family. When we’re working on that film and the feature, the Langille family provided us with photos and home movies. Through the scraps and fragments of those photos and home movies, the two miniature artists, Shelley Acker and Iris Sutherland, were able to re-enact with as much historical accuracy as they could what the Langille family home looked like.

POV: Is the original home still standing or were you mostly drawing from memories and archival material?

JT: I have a production company in Halifax Nova Scotia called Peep Media with my production partner, Jessica Brown. We made a trip to Oromocto where the Langille family had lived. Bernie, Sr. had been working on the base at Gagetown, New Brunswick in 1968. He and his family lived in the married quarters that they provide for military families in and around the base. We went to Oromocto and gathered information for our miniaturists so they could start building the exterior of the Langille family home. It’s from photos and home movies that they were able to build the inside of the Langille family home, so we did a bit of both.

POV: How much did you discover in the process of making both the short and the feature? Did you know everything by the time the short was done?

JT: We learned a lot more. The short was a recounting of what Bernie knew as the event itself. When we were able commission the feature for the documentary Channel, we took the series of questions that Bernie had after he found his grandfather’s SIN number on his grave marker, which he was able to use to track down the medical examiner’s report. Reading the medical examiner’s report led him to have more questions. For instance, he was really intrigued by the fact that his grandfather supposedly had fallen down the stairs because there were no bruises on his elbows or arms. He wanted to know why there had been a military doctor who was put in charge of Langille when he was at the Fredericton airport waiting to be transported to Halifax. That military doctor ended up assaulting Langille, Sr. who, at that time, was very seriously ill with a skull fracture. There were eyewitness reports to this assault. He wanted to know who this doctor was and why he was assaulting his grandfather. We made our own call to the public to come forward if they had information. We found a couple of people who are in the documentary through that method.

POV: What impact did COVID have on your production? Did the method with miniatures give you some flexibility?

JT: I have no complaints. I was able to continue doing my work through a global crisis. That’s a miracle to me. We were getting on a roll with Bernie, taking him to different places where we had started to discover some answers. We were only a few weeks into shooting our actuality portion of the documentary when the world shut down. Then we were able to start resuming filming that summer, which was fortunate, but mindsets had changed. The crew’s mindset, my own mindset, and of course, Bernie and his family’s mindset had changed.

We had gone from Bernie tracking down the answers to this 50-year-old event that had affected his family, then Bernie and his wife had their first child in the midst of the pandemic. Priorities shifted radically, as they do. I think that’s been a common experience for every single person in this pandemic: what you thought was important before the pandemic has changed because we’ve all gone through this collective and, at times, very frightening experience. We were able to continue filming and that was fortunate, but it did change everything.

POV: Do you think this process has brought closure for Bernie and the Langille family?

JT: When we started, Bernie, Jr. would talk about how this affected his family, but it hadn’t really affected him that his grandfather was someone that he had never met. Bernie, Sr. died 15 years before he was born, so the strange dark family fable that he had grown up with was something that he could be removed from and was almost theoretical to him. When he went to visit members of his family who agreed to be part of the documentary, and they recounted their memories of the event, it became clear to Bernie the emotional toll the event had taken on his family.

There’s a scene in the movie where he’s speaking to a psychologist who has a specialty in working with military families. The psychologist says, “Are you concerned if you come across information that your family may not want to hear?” They discuss how family narratives can become a fundamental part of someone’s identity. I think that’s true. We all have family narratives. Sometimes we only know bits and fragments of the stories and we become attached to them even though we don’t know the full story. That’s exactly what happened when we made this film: we encountered information that was difficult to hear and changed the story that the family had been telling themselves.

POV: How did digging into a family’s history make you look at your relationship with your family?

JT: I come from a very dysfunctional family [laughs], so I think part of the reason I was drawn to Bernie and his story because I was drawn to this idea of family narratives being a strange legacy. They’re a strange inheritance. In some ways, we are aware of how they affect us, and, then in other ways, we are not aware at all of how these things affect us. I think there’s hope in awareness.

There’s a researcher in the States called Dr. Brian Dias, and he did an experiment with mice and the smell of cherry blossoms to study the effects of intergenerational trauma. Every time he introduced the odour of cherry blossom to this particular generation of mice, he would also give them a shock. They would associate that with the smell of cherry blossom, and they soon had a trauma response to that smell. He found that this trauma response to the odour was passed down to subsequent generations even though they did not experience the negative shock associated with cherry blossom. He saw that trauma response was passed down. Dr. Dias also found that you could reverse the effects of intergenerational trauma when you are aware of them. When you can name it, you can work on it and reverse it. After the birth of his daughter, Bernie wondered about the fourth generation of Langille coming into the world. Was he passing on this story to the next generation, or was something going to change in his generation?

POV: That’s such an interesting story. The cherry blossoms in Toronto usually come out around Hot Docs, so you should tell that story to the audience and see what happens when they smell cherry blossoms. [Laughs.] In terms of your history, though, you have such an interesting background professionally working as an actor and has a director of both drama and documentary. How does a performance background help while directing a film like this one? Bernie has a great dramatic flair as an interviewee, so was that something you worked on with him?

JT: Bernie’s way of telling the story is his own. He is a great protagonist in the sense that he’s an odd duck, which I actually really like about Bernie. He’s very precise and detail oriented. That really comes in handy for a story like this one that has so many twists and turns. It’s actually wonderful working with artists who create in miniature because they are also detail-oriented. For instance, there’s a wonderful set based on Larry Langille’s apartment. At one point, Iris asked me if Larry Langille smoked, and if I could ask the Langille family if he smoked and how much. She wanted to know how much he smoked each day because that would affect the colour of the paint and stains on the walls. It is all about the details when you are working with artists who create imagery.

POV: That is fascinating. The miniatures do have such great details. What about your background in performance specifically, though? That seems really central to this film.

JT: In terms of my background, I always think that if you can do more than one thing, why wouldn’t you? If I’m working as a writer, or if I’m working with an actor, or if I’m an actor working with a director, or as a director in the world of fiction or nonfiction, the thing that remains constant is that I’m serving story from different angles. The ability to move from different jobs around the world of story keeps me invigorated. The jobs inform one another and come in handy. As a documentary director, the fact that I also have a background as an actor means that I can remember and know intimately how it feels to go in front of the camera and how vulnerable you can feel, and perhaps what you need in the environment to make yourself feel more comfortable.

I often work with the same crew in part because they’re extremely talented, but also because I selected them for their temperament. When it comes to documentary, the temperament of a film crew is supremely important. You can’t have big personalities taking all the air and space in the room. In a documentary crew, the priority has to be the documentary participant. The priority has to be on the relationship between the documentary participant and the director. I’ve been lucky enough that the people I work with are not intrusive when the participant is being asked to open up in front of the camera. At the same time, they are supportive of the participant. In every documentary that I have shot, the participants always develop their own relationship with the crew. That relationship facilitates my work and what we’re trying to do is all connected.

Bernie Langille Wants to Know What Happened to Bernie Langille premieres at Hot Docs on April 30.