He tells me his dreams, sometimes, when I run into him, which is more often than not these days. It seems we are intersecting, like it or not, ready or not, but I can’t remember the dreams. They are so fine, so perfect, I remember thinking each time he tells me that they should be a movie, only that would ruin it, because they are finer and more beautiful than anything presently grazing our screens. The act of turning them into movies could only lessen them and so they must remain between us as a promise. A promise I can’t help forgetting.

In the pages of NOW Magazine, Cameron Bailey picked Daniel Cockburn as Toronto’s best new video artist and I can only agree. He has a rare literary talent which he serves up with visual élan, smart design sense and a playful philosophical project whose deeply lived roots is leavened throughout with humour. In fact, he’s most serious when he’s having fun. And even though his work appears as audio-visual feuilletons—essayistic briefs, missives from the margins—they possess an uncanny narrative order (though it is a narrativity steeped in the twentieth century, not the nineteenth).

Here in Toronto we are living in an age of commissions. Not Zanuck and Mayer but Charles Street Video and V Tape. Could you imagine making art about themed appointments? And he can. Each and every one he can. Of course there is a bravura excitement around these home brewed evenings, balanced by an exactly proportional degree of disappointment in the afterglow. Oh, it’s only… Except for Cockburn. I don’t know what it is. Perhaps it’s the same thrill speckled rabbits get from choosing a moment to cross the road, which most nearly coincides with oncoming traffic. The adrenalin rush of failure. The sense that others are watching, or perhaps it is the more covert run of blood against blood. Whose is bigger? Faster, stronger, made to last? Not that the Canadian art scene is built on winners and losers, au contraire, the reigning philosophy insists that a democracy of attention be granted to anyone who asks. Is it any wonder the work often appears small and grey? But not Cockburn’s. Not with all those pop stars swimming from the mix. And he hasn’t left his Wittgenstein behind either.

He burst into my brain with Metronome (2002), a movie that remixed an artist’s diary and found footage smarts in a meditation on the body’s mathematics. The ratio of walking and heartbeat is explored; he narrates the mystery of stereo, of how it might be possible to hold two thoughts at the same time. A series of movie associations follow, slips, which dissolve one star turn into another, faces become books, then ideas, and back again. Rhythmic infinity (when a groove becomes a loop) is the author’s definition of hell. No matter that there are so many thoughts to think, Cockburn confesses that his experience turns around just a few. What clings to him are repeating moments, already mirrors for his own obsessions. His joy and despair at this recognition is that memory is founded on repeating, but at the same time the very act admits the threat of over and over.

Superimposed on his heartbeat, which here is a stand-in for the inner monologue, are pictures which arrive from elsewhere, secondary experiences which storm the screen with an abyss of another kind: the promise of pleasure without consequence. It’s only a movie, right? But this cinephile, who is busy turning himself into an image, tries to weigh the cost of his mediascape. “I wonder what the polyrhythm of all these sounds and movies look like?” muses Cockburn. Once again he finds in the movies a correlative for his own preoccupations: the act of ordering and making meaning. Deploying an elegant clip collage he demonstrates that films are models of ordering, impossible to imagine without it (what does such an accumulation of capital look like? A face, a kiss, a blown up car, a prison) but at the same time he notes this ordering leads to despair. A perfect world, in which everything can be known, is perilously close to fascism’s ‘politics equals aesthetics,’ but without striving to know, where is happiness? “All this too is seductive, aesthetic, perfect despair.”

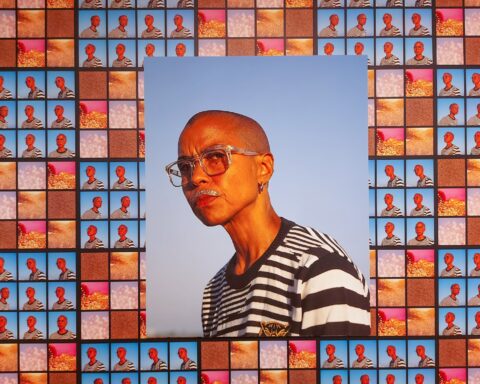

Weakend (2004) was another commission. This time commissioning body FameFame required that all media derive from Schwarzenegger’s sci-fi doppelganger thriller The Sixth Day. Cockburn replays it as an ingenious creation myth, opening with Arnold’s dreamed double encounters, the looped abyss of eyes within eyes, a mosaic of multiplying greetings (“I’m Adam Gibson”), a looped and therefore endless descent, a montage of Arnold’s reaction shots (slowed to approximate understanding with faux triumphal accompaniment), a pulsing screen atop a screen (even the frames are replicating). It closes with a hilarious cut and paste monologue that bears repeating; the words, remember, are all derived from the original movie, respliced into a different order, sometimes syllable by syllable. How often, after all, does one hear the Governor speak the dreaded words: video artist?

What are you doing to me? I don’t think this is very funny. Who are you? You think you are a media artist because you control me with a piece of software. This is terrible. This is not natural. This is creepy. You know that. I want my life back. You think you are God because you control me. No, I don’t think you are God. I don’t think you are a media artist. You are a sick bastard. You can go fuck yourself. I’m going to take my life back.

Love me two times Frankenstein and I’ll enjoy you from both ends, making and unmaking you. I prefer your image anyways, the one that’s on my hard drive, cooking all night with new changes. Wait until you see the new you. Though looking forward is something only I can do. You are condemned to look back.

Is this only the pressure of too many cameras, the relentless surveillance of the supremely visible, the inflated surrogate, multiplied and sprayed across screens around the world? Or is this also “our” momentum? Are we also inside a matrix of branded zones, which we announce with the clothes we put on as images, the picture foods we eat, the sitcoms we are busy living? What happens when a mirror looks at itself? Here at last, in this weakened state, philosopher Schwarzenegger is allowed to muse on his too many years spent replicating, offering us warning and prophecy about our own hopes, even as he runs out of his own. He is spoken by the artist, like we are spoken by language, though here in the gridlocked codes of narrative we can see the tensions of power at work as an image is made to appear (“as if”— behind every image is the promise of “as if”) as if it hoped only to escape its own finitude, its limits, sensing that something else might lie outside the frame. (But how to speak of this in a language which forbids it? Which serves to replicate its own coding, demonstrating its own usefulness and by so doing wondrously repressing any expression that might lie outside it?) It’s perceptual SM, the director’s fave genre, one he is making all his own. Longing and limits are the heart of this Cockburn short made for a programme, which featured a dozen other studies (though none as finely tuned) also served cold from The Sixth Day, a program appropriately entitled Attack of the Clones.

He’s not afraid of being funny, and it’s ideas he finds amusing, which in his hands is only the other side of terror. In Stupid Coalescing Becomers ( SCB, 2004) Cockburn shows us a world where everything is reversed: paper uncuts itself, cigarettes unsmoke, broken lightbulbs re-form, pills re-gather and in the final image, the artist himself flies out of the frame. A simple jump off his porch becomes, in his capable hands, a sight gag worthy of the old comics. Concise, witty and delivered in a deadpan monologue of mock exasperation (Cockburn speaks with many tongues, he is also an artist concerned with performance), SCB is a protest against the tyranny of forward moving time, a home brewed science fiction short which offers a serial demonstration of a single premise. Of course it is the inevitability of time’s forward motion that is the rub; he offers clock time as a prison warder then gleefully rips it apart, sends it hurtling in another direction. Even if it’s only for a moment, in a movie, he offers us this freedom. That it is also a home movie, made for nothing but the time it took to dream it all up is tribute to this artist’s ingenuity.

The more often I see Cockburn’s work, the more urgent becomes my necessity. Addictions are born in these oases of image. And I am not alone here. It’s us now: I can speak in the third person. We need these pictures, these thoughts on pictures, these new frames from which to glimpse the impossible.