The best documentary filmmakers don’t want to wrap their subjects up in fine funereal cloth and treat them with phony sanctimony. Nor would any self-respecting artist want to be thought of that way. When we look at documentarians looking at subjects, we should expect that their creative impulses will be as resonant as the people they’re profiling. If you read literature, it’s obvious that Samuel Johnson wouldn’t have half the reputation he has without his brilliant scribe, James Boswell, and, in contemporary times, another Johnson, Lyndon, is more than lucky that the superb biographer Robert Caro has seen fit to make him the subject of a magnificent series of books.

Such musings may seem pretentious in describing Joannie Lafrenière’s affectionate and humorous treatment of Gabor Szilasi, the great Hungarian-Canadian photographer. A photographer herself and an admirer since her adolescence of Szilasi’s precise, humanistic documentary work, Lafrenière made a film, Gabor, which is less about his camera practice and more about the kind of life he’s led in Quebec since coming from Hungary when he was 29. Clearly embracing freedom after the crushing of the 1956 Hungarian revolution, Szilasi was able to establish a reputation as a documentary photographer first at the Quebec Film Board and latterly as a sought-after freelancer and professor at Concordia University.

Lafrenière has taken the risk of treating Szilasi as a friend, a fellow documentarian, who is ready to collaborate in an honest portrait of himself as a man as well as an artist. Her approach is one of genuine warmth while never missing the salient moments in his career. As a biographer, she’s less of a Robert Caro and more of an Agnès Varda: someone who wants to have fun and imaginatively engage with her subject. We see the two in lyrical and playful set ups, Gabor and Joannie dueling with cameras while making photos of each other, standing and gazing before entering a car, ready to make another journey through rural or urban Quebec. The contrast in their dress is piquant: Gabor, the artist and bohemian, still slim in his 90s wearing a beret and grey clothes; Joannie, attractive and effervescent, in colours, offering an image of vivacity and well-being.

Her film takes us to Charlevoix, on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, and in the now touristic Laurentian Mountains district of Quebec. It is here, on the Isle de Courdes and other small communities in the area, that Szilasi made a memorable series of images in the early ’70s, which he has continued over the years. Lafrenière, who first met Szilasi at the Photo Gaspésie festival in 2015, felt the connection between him and the people of northern Quebec, especially in the region of Charlevoix. The photography he took there was important in creating his reputation.

For the making of the film, Lafrenière proposed that they travel back to the area once again. We see Gabor eating poutine, being invited back home for a conversation with two locals, and most impressively, going over old photos with the woman who acted as his fixer a decade earlier, introducing him to many people in the region, all of whom were happy to have a picture taken. You can see how relaxed Gabor is with people in Charlevoix, which doubtless made it easier for him to make intimate shots in the area.

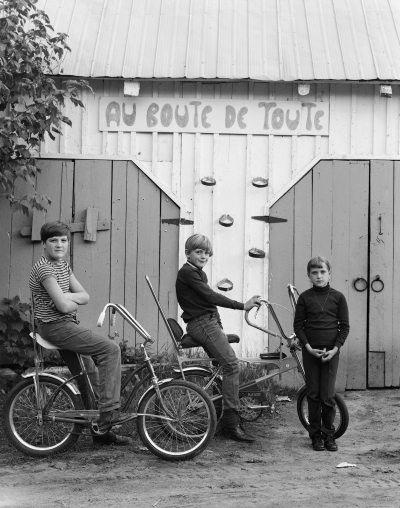

The photo “Au bout de tout” is a fine example of his approach. We see two boys sitting on their bicycles, accompanied on foot by a girl, likely their sister; all are looking at Szilasi’s camera. They’re in the back of a one-story building, which has two sheds attached to it. Szilasi doesn’t make the shot geometrically precise since his main interest is in whimsically capturing a moment shared by three children during a summer’s afternoon in Charlevoix. It’s a shot that appears to be unpretentious but is expertly executed in a region where Szilasi mainly documented adults. It is lovely to see a record of young ones there.

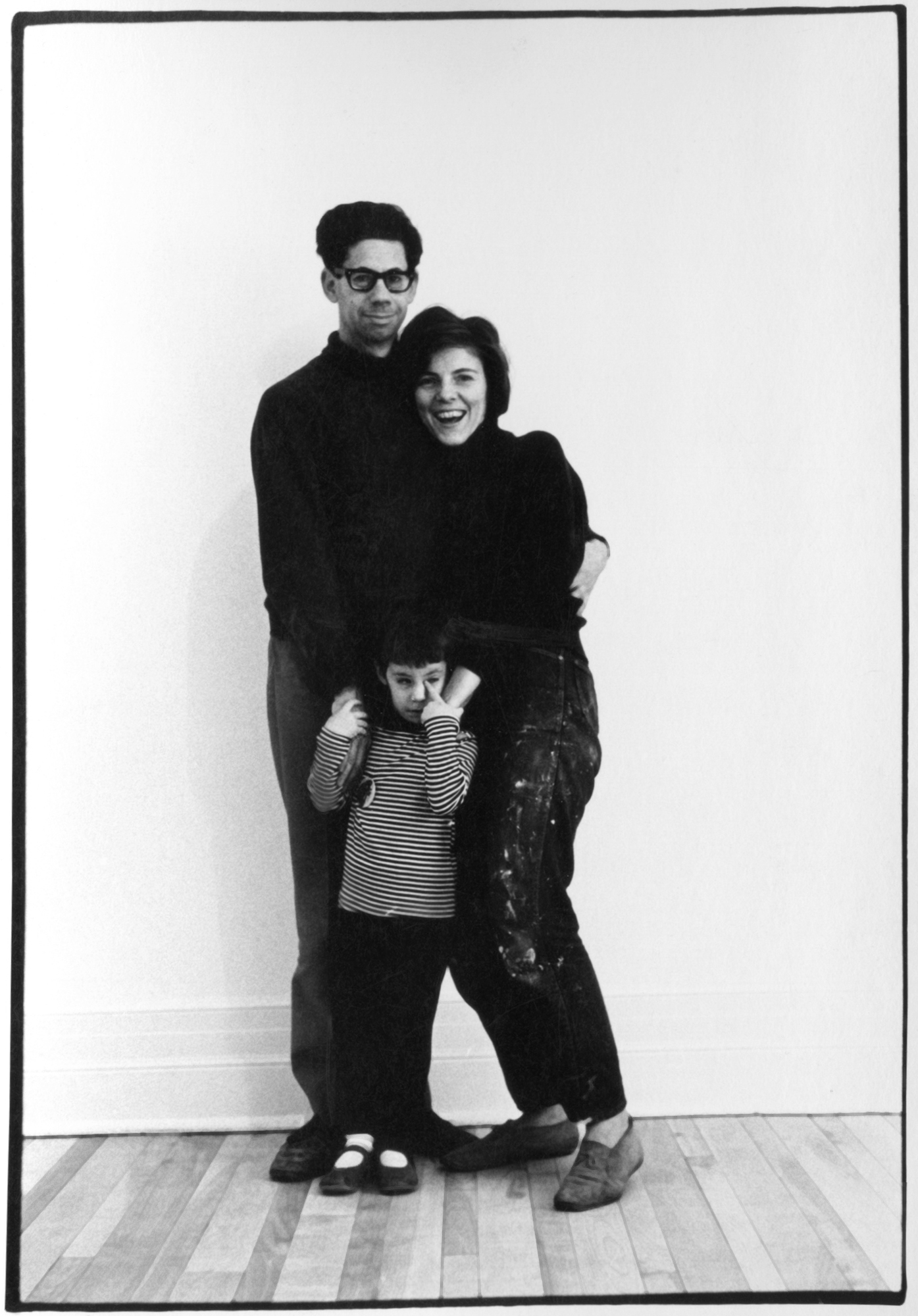

From Charlevoix, Lafrenière takes Szilasi back to Montreal, where the photographer has lived for more than 50 years. Understandably, she concentrates on Szilasi’s family and friends, who have been the key figures in the life of a man who is, in many ways, quiet and reclusive. People respond to Gabor Szilasi as a reserved artist, who treats those he enjoys with forthrightness and a mild wit. Lafrenière calls him “nice,” but she knows that he’s more than that: he has an old-fashioned European politeness and charm, which is set off by a shock of white hair underneath his bohemian beret, erect posture, and dark clothing. He’s married to the painter Doreen Lindsay, who recalls that after several dates, seemingly all at cultural events, he asked “when will we get married?” She still laughs about if a half century later—not “should we” or “will you,” but simply “when.” It shows Szilasi’s muted self-confidence: he was in love and he’d observed she was, too. And he wasn’t wrong.

In one of the most charming scenes in the film, and actually before the trip to Charlevoix, Joannie gives Gabor a haircut in a shop that has history for both of them. Lafrenière lived above it when she was younger and Szilasi had shot it many years ago. In a characteristic move, Szilasi shares the photo with Lafrenière and she shows it to the shop’s proprietor. They both respond with glee, offering up anecdotes. Though Szilasi isn’t at the barber shop to make photos, this is the same technique he knows is effective in Charlevoix and elsewhere: showing pictures gives his potential subjects a connection with him before any shot is taken.

But this is only one entry point into a marvellous sequence. The good humour between Szilasi and Lafrenière is evident throughout as is the wonderful presence of Gabor’s grandson, Luca. Eyeglasses with goofy concentric circles in the middle of each lense, given to them by Lafrenière, are used for fun by Szilasi men from two generations. They’re an amusing sight and what they see must be funny, too. The barber shop owner lets Luca know that he has a lot to live up to, but what’s moving is that the lad is aware of that already.

Lafrenière devotes an important amount of time to Andrea, Luca’s mother and the only child of Doreen and Gabor. We see her in an amateur film made when she was still in a pram with Doreen pretending to let loose of the machine and then running to retrieve it and her baby girl. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the film is filled with wonderful archival photos and film footage since the Szilasi family spent their time with fellow artists. Andrea speaks of her mother and father with genuine fondness, telling of a childhood and adolescence spent with parents who always treated her with affection.

It’s fascinating to hear Andrea’s anecdote about a difficult moment she faced in her late teens. She was going through a crisis with a boyfriend and sought out her father at his office at Concordia. Gabor listened to what she said with interest and asked her to sit in a chair and look out at a window with a view of downtown Montreal. As she did so, he took pictures of her. That was his response: enigmatic but revealing of who he is.

Before meeting Doreen, Gabor, as a young immigrant, immediately embraced Montreal. The same year, 1959, that Montreal became his home, Szilasi made one of his finest photographs. “La religieuse de l’aéroport Dorval” is wonderfully composed. The forefront of the picture depicts a nun in full garb from an angle where we can see that she’s looking at an airplane without showing her face at all. Her power is in the lack of a personal identity: she is a personification of the Catholic Church, which held a dominant position in Quebec before 1960, when the “Quiet Revolution,” modernized the province. On Dorval Airport’s runway is an airplane, large for the time, but soon to be surpassed by others as a greater focus and investment in international travel at Dorval took place the following year. The darkness of the nun makes a startling contrast with that of the white plane and bright field; it’s as if Szilasi could already see Quebec’s future in his shot.

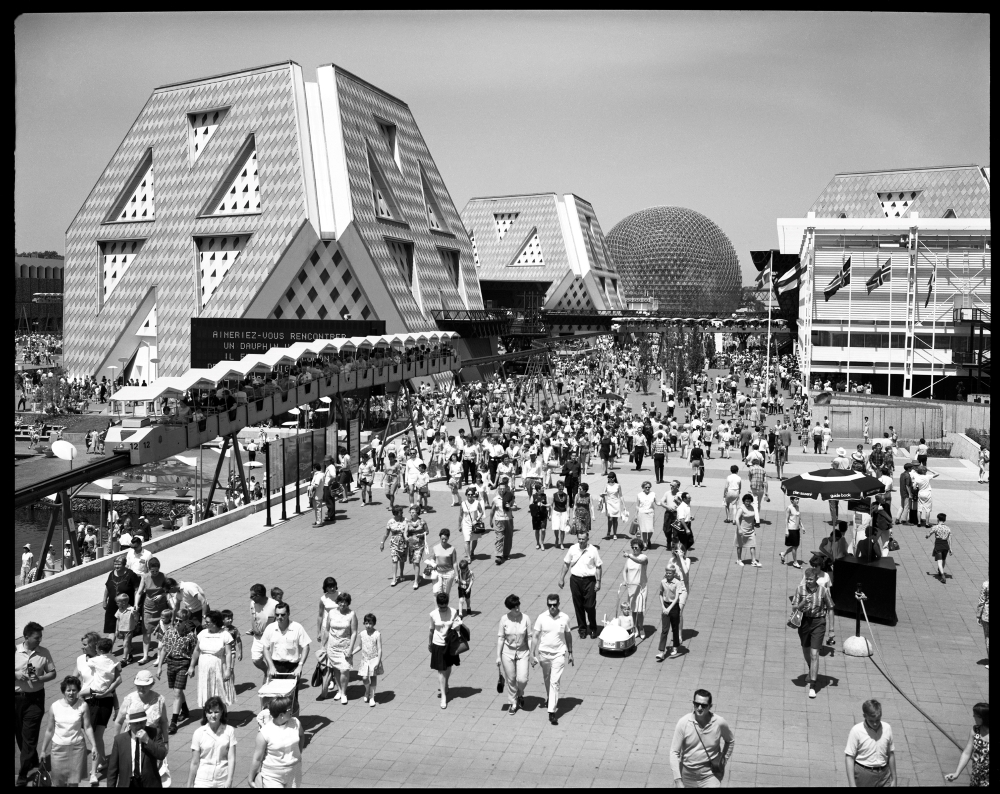

From the Sixties onward, Szilasi has been a chronicler of Montreal’s changing landscape. He’s photographed major events, vernissages, architecture, and the people who live and work in the city. His photo “Expo 67” is an early example of what he did for decades. From a view above the fray, Szilasi shows multitudes spilling in and out of the frame, displayed characteristically against astonishing architectural sights, enjoying one of the greatest events in Canadian history.

Lafrenière’s film follows Szilasi as he celebrates his 90th birthday and, right around the same time, a retrospective of work capturing Montreal and its arts community. Just as Doreen Lindsay and Andrea Szilasi share stories with the filmmaker about Gabor, so does Michel Campeau, a great photographer and one of the family’s closest friends. It was at the vernissages, the many beautiful art openings, that Doreen and Gabor met their closest friends and experienced cultural events that English Canadians could only dream of attending. This was the time when the Szilasi duo met and became friends with John Max and Sam Tata, among others. In the film, Gabor is given a party at Michel Campeau’s backyard, where intimate slides are projected, including some from Gabor, mainly of his family, but one of a friend, a fellow photographer, who has since died. Such is the fate of all of us but it has a particular impact for Szilasi, whose good health has allowed him the sad responsibility of saying goodbye to many great friends.

During his many years as a freelance photographer, Szilasi has taken on commissions, but he’s also created work with no constraints. In another masterpiece, “Salon Auto Place Bonaventure,” Szilasi engages in a brilliant example of what photo curator, writer, and former professor David Harris calls “environmental portraiture.” Szilasi has created an existential likeness of an auto salesman who is immeasurably confident of himself and the car he is representing. Placed implacably in the middle of the shot, the Ford Mercury salesman is almost mirthful, in front of an automobile, which gives him immense pride. In his beautifully written catalogue accompanying a touring Szilasi show, Harris defines this type of photography as “a genre in which the setting—a person’s home or workplace…plays an essential role in elucidating the subject.” That’s what is seen in this wonderful shot—and many others by Szilasi.

Who is Gabor Szilasi? How did he get that way? Joannie Lafrenière tackles those essential questions towards the end of her film. In an extraordinary scene, Gabor reads a statement about his mother. He’s too moved to simply talk about her. Szilasi was born Jewish though he was raised Lutheran in the desperate hope that anti-Semites wouldn’t hurt or kill him or his family. In 1944, as the Nazis attempted to kill all the Jews in Europe, most of the Szilasi family was imprisoned. His mother was sent to a concentration camp, where she died, but luckily, the rest of the family was released, probably due to bribes of officials. Gabor’s brother and sister died young and he and his father were caught trying to escape from Hungary and the new Communist authorities in 1949.

Gabor Szilasi had been studying medicine but the Communists wouldn’t allow him to do it after his attempted escape. After years as a labourer building the Budapest Metro, Gabor acquired a Zorkij camera, the Soviets’ copy of the famed Leica, which documentarians starting with Henri Cartier-Bresson used for their quick, brilliant shots of life unadorned. He’d found his métier and was able to produce brilliant shots quickly. One of the best is “Motorcyclistes au lac Balaton,” an amazing picture incorporating the blur of motion into the capture of a couple of young athletic riders, racing around the periphery of Hungary’s most famous lake and resort region. It’s a vivid and exciting shot that most likely persuaded the Film Board to hire him in Quebec.

Although Lafrenière includes footage of Gabor and Andrea in Budapest and his visit to an aged friend he knows from the gym, Szilasi reveals little of himself. He is the proper husband, father, grandfather, and friend, who didn’t even speak much during the exuberant vernissages of his younger days, preferring to take photos. The immense sorrows he experienced in Hungary are subjects he prefers to address internally. As a great documentarian, he observes as much as he can, appreciating what he sees in what Harris calls “the eloquence of the everyday.” Gabor Szilasi resembles the pianist watching the passing crowd in Truffaut’s Tirez sur le pianist (Shoot the Piano Player). Quietly but with great affection, he has devoted his time to photography, which he believes is like “a poem,” offering his best to his photo subjects, his family and friends and no doubt to Joannie Lafrenière for making this heartfelt portrait.