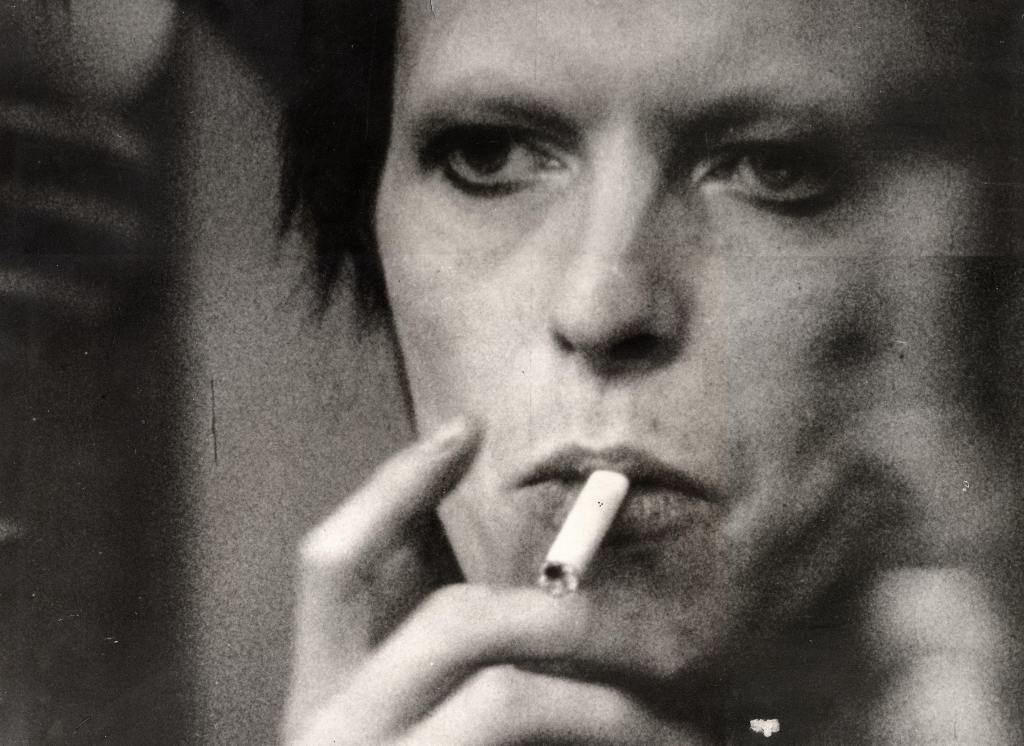

Over a renowned career, David Bowie was famous for never standing still. From his early, twee folk-rock period to the alien adventures of Ziggy Stardust and on to the Thin White Duke phase, pop superstardom, and the mercurial theatrics of Blackstar, Bowie was constantly hungry for new modes of expression.

The same sense of discovery can be found in the films of Brett Morgen. From his groundbreaking incorporation of animated elements in the Robert Evans doc The Kid Stays in the Picture (2002) through his kinetic editing strategy with found footage for the extraordinary O.J. Simpson film June 17th, 1994 (2010), to award-winning projects about iconic characters like Kurt Cobain and Jane Goodall, he has developed a unique way of incorporating sound and vision into his film work. His documentaries constantly shift expectations and challenge viewers to go along for the ride.

Morgen’s latest film, nearly a decade in the making, is Moonage Daydream. It’s a perfect culmination of form and function, with an artist exploring the work of another iconic talent. Morgen takes Bowie’s own output and uses it as a mirror to explore both the music and the man, resulting in a film that’s a sensory onslaught while being intellectually and emotionally profound.

POV spoke to Morgen while he was at Karlovy Vary, a few months after his dramatic Cannes premiere, and prior to Moonage Daydream’s TIFF premiere and international roll-out on IMAX screens.

POV: Jason Gorber

BM: Brett Morgen

POV: You don’t start your film with “Space Oddity.” You don’t start with “Life on Mars.” Instead, you start with David Bowie live in an era where a lot of people thought he might no longer be musically relevant. What is your favourite Bowie record, and why?

BM: The easy answer would be 1971’s Hunky Dory because it’s traveled with me through so many decades. It’s like my favourite Sunday morning album. But I think through the process and experience of working on this film, I’d probably say 1995’s Outside became a really essential album for me. If I have a regret about Moonage, it’s that the film and the arc did not afford me the opportunity to do a deeper dive into the mythology about Outside. One of the really illuminating assets I received were all of David’s ad libs for the dialogue portions of that album. We could spend a whole hour talking about Outside!

POV: How do you begin to tell Bowie’s story?

BM: After eight months of banging against the wall, I started to figure out the script. I leaned heavily on Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces and that heroic journey. Brian Eno was going to be the Yoda character and would come into David’s life right when he needs it in ’76. Then when David loses his way, Eno returns for his wedding and then leads him to Outside in ’95 for the reunion where David goes back to a more freeform way of creating.

POV: I’ll note for those that haven’t seen it yet you didn’t do that.

BM: No, because I felt that the throughline culminated with the live performance of “Hollo Spaceboy,” which is, of course, from Outside. There was nothing else to say or do, it would have just been repetition.

POV: Speaking of space boys, instead of doing Star Wars, which Lucas purposely structured as a Campbellian film, you chose to follow Kubrick’s lead instead, incorporating some of the visual flourishes and esoteric, even psychedelic nature of 2001.

BM: It’s funny— I was talking to someone who was working on the trailer, and the first said,, “It’s it’s really not.” It’s kind of Hero with a Thousand Faces with a lot of salad dressing put on to it.I was also thinking aloud about The Iliad. The only difference is that Bowie is creating the storms for himself. What really sealed it for me is that he was creating, and when he stopped and got stagnant, that’s when he lost his way.

POV: When the ship’s sails no longer have wind, the sailors are there waiting for their next destiny.

BM: But I don’t think we answered the question about using “Hallo Spaceboy.” As a culture, we take genre for granted. Genre is like the cradle, it protects us. It gives us a compass when we experience any art form. It goes back to the beginning of comedy, tragedy, what have you. One of the biggest challenges going into Moonage Daydream was knowing that we were not going to be part of a genre. That is a rarity, for better or for worse.

If you walk into the film thinking you are going to see a biographical documentary, you will be disappointed. It was paramount that we set a covenant in the first 10 or 15 minutes, to establish this new genre. That’s what triggered the Nietzsche “God is dead” quote in the beginning of the film, which was a very late addition. Then “Spaceboy” becomes really important because it immediately tells you that we’re not going to follow a linear chronology.

POV: Here’s the danger: It comes across as pretentious.

BM: Why is that a danger? What’s wrong with pretension?

POV: Even obnoxious. Even detrimental to fans of the film. At some point in time you needed to have the chutzpah to not give people what they expected, which strikes me as being exactly what David would have wanted from this film. Was there an impetus to purposely not give people what they expected? In other words, was it expected to not give the expected?

BM: I had a joke when I was making the film. I’m pretty sure nobody has the Pet Shop Boys’ remix of “Hallo Spaceboy” on their Bingo card as the first song in the David Bowie documentary! I opened my film Chicago Ten (2007) with Rage Against the Machine. At the time, I was like “Yeah, I’m really going to mess with their expectations!” In retrospect, I wouldn’t have done it, and I feel like it alienated certain people. I’m conscious of the fact that there are people who aren’t as familiar and don’t celebrate latter-day Bowie music the same way we do.

I suppose a part of me was saying, “If you don’t like this, then maybe this isn’t the right film for you, because this is for me, as much as part of the canon as anything else.” By going from that first song to the more familiar “Ziggy Stardust,” we’re liberated. Early on in his performance of “Freecloud,” I cut to Bowie in the future at an airport and you start to get this loose sense of interplay with time: there’s no beginning, no middle, no end. It allowed David to have a continuous dialogue with himself and commentary upon himself.

POV: What does Pennebaker mean to you?

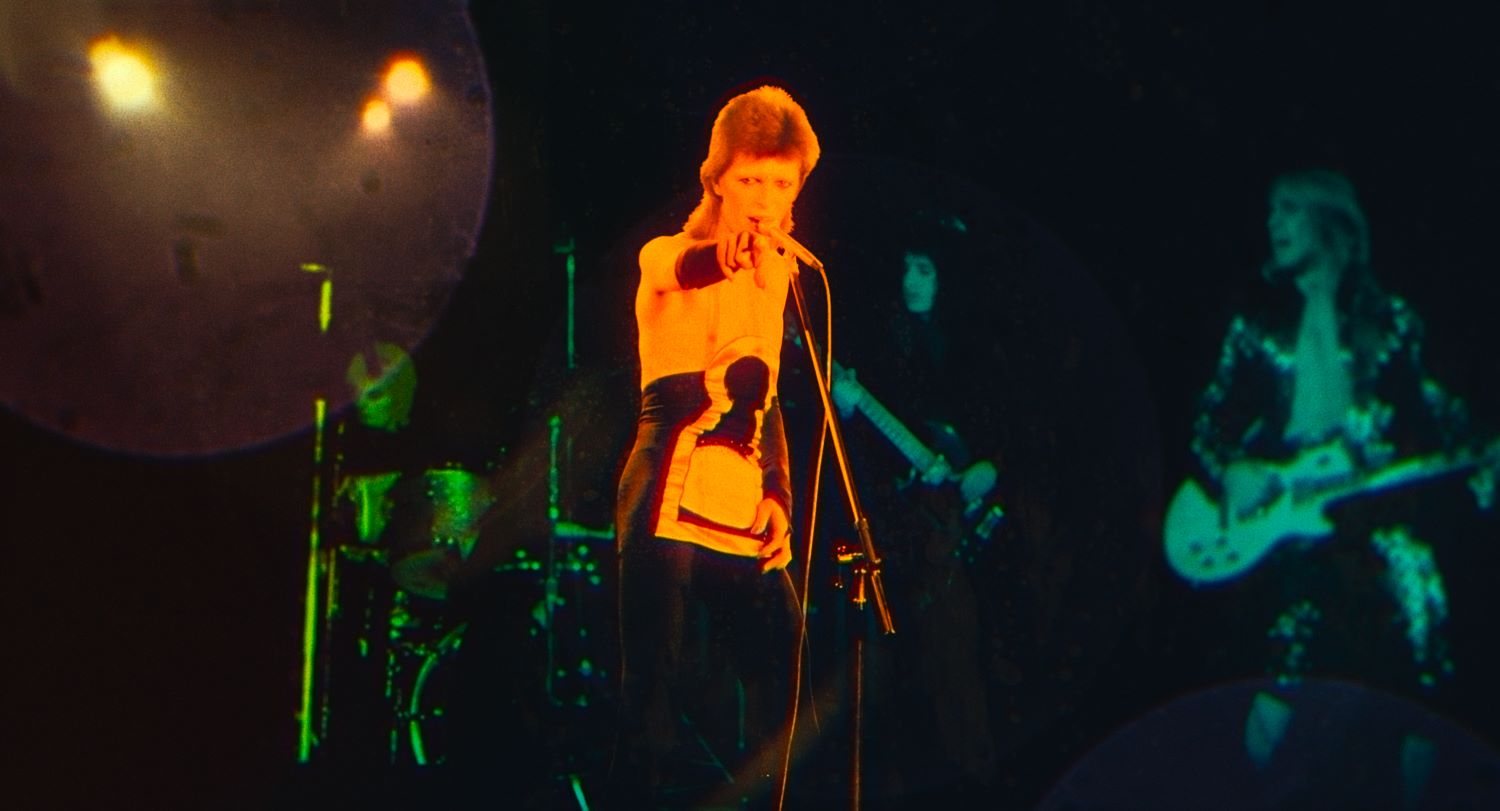

BM: Pennebaker is my entry to documentary before I knew there was a genre called documentary. I think the only “documentaries” I ever probably saw were That’s Entertainment and Pennebaker films. And I did see the Pennebaker’s Ziggy Stardust film when it was released in ’83 I think at the UA 6 which was south of Wiltshire Boulevard and Westwood in a really long, cavernous theatre with like four other people. My experience of it then was that it was really kind of grainy and red and kind of out of focus. I definitely bought the soundtrack on vinyl. When I started reading and doing research about David, the image of Ziggy that was being conjured up in the writings and of course from the album were quite different from my early memories of the Pennebaker film. So this film is me going back to my childhood, channeling my 13-year-old self and having the opportunity to kind of create Ziggy in the way that I believe he was designed conceptually, but hasn’t been allowed to exist in the documentary form, by Pennebaker or anyone else. They tend to dissect Ziggy as opposed to embracing the mystery.

Pennebaker was my entry to docs before I knew there was a genre called documentary. I think the only “documentaries” I ever saw back then were That’s Entertainment! (1974) and Pennebaker films. I saw Pennebaker’s Ziggy Stardust film, in ’83 I think, at the UA 6, which was south of Wiltshire Boulevard and Westwood, in a long, cavernous theatre with, like, four other people. My experience of it then was that it was really grainy and red and out of focus. I bought the soundtrack on vinyl. When I started reading and doing research about Bowie, the image of Ziggy that was being conjured up in the writings, and from the album, were quite different from my early memories of the Pennebaker film. This film is me going back to my childhood, channeling my 13-year-old self and having the opportunity to create Ziggy in the way that I believe he was designed conceptually, but hasn’t been allowed to exist in the documentary form, by Pennebaker or anyone else. They tend to dissect Ziggy as opposed to embracing the mystery.

We had access to all of the outtakes, and we did 4k scan of everything that was shot for the Pennebaker film. I sensed that there was probably some material, when working on a Moviola, that they dismissed. I had colour correction tools that weren’t available then. If you know the film intimately, as soon as David comes on in “Freecloud,” there are different hues that didn’t exist in the film [but do now].

We added some purples and some yellows and some oranges and we’re painting all of that stuff. And then Stefan Nadelman did some wonderful photo animation for those sections that introduced a bunch of complementary pinks and the main palette of the film.

POV: So, that’s why it took six years?

BM: [Laughs]. Seven years ago, I had the idea to do an IMAX musical experience.

POV: Always about Bowie?

BM: No, Bowie was not going to be part of it at all. It was going to be a series of 15 films. This was back in 2015, and Bowie was commercially weak when trying to launch a global franchise, as strange and add as that sounds today. Something happened on the day he died, to quote a song. Since he passed, his popularity has grown exponentially. In 2017, he was not in the top ten of deceased recording artists people were listening to, and at last recording, he was number 1 on Spotify. I think that speaks volumes to how much David continues to provide a soundtrack for the times we’re living in.

So, eventually, I started turning my compass to David. Shortly after he passed, I reached out to his executor. I had had a meeting with David in 2007, and Bill Zysplat, his executor, . . .

POV: Whoa, hold on a sec – what was it like meeting Bowie?!

BM: Well, if I had met him after being immersed in his art for five years the way that I have been, it would have been a totally different experience. Generally, when I’m pitching a subject, I’m try to do as little research as possible. I had done The Kid Stays in the Picture and The Chicago Ten and had started to earn a little bit of a reputation for being a person who does non-traditional non-fiction. A woman I knew worked at Sony BMG, not associated with the BMG who ended up co-financing the film, and she said “We just got David as a client, and I really want to do a Bowie doc, but he won’t do a Bowie doc. Can you come up with a pitch for a film that’s like a doc and uses the catalogue, but isn’t really a doc?”

I met with David at his office on 57th street. It was David, his assistant Coco, his manager and executor Bill Zysplat, and Holly that I knew from Sony BMG. We were in a very small meeting room that could basically house no more than four people. David was wearing an army jacket, I believe a white V-neck t-shirt. What struck me most upon meeting him for the first time was we were I think similar height and I kind of wasn’t expecting that because stars are usually a bit shorter. You could see how he could disappear at that time, walking down the street, but also turn it around. There was nothing really intimidating about him until we started talking, and he immediately didn’t waste too much time before he launched into an absolute assault on Chicago Ten.

I was taken aback. He had made some complimentary remark about The Kid Stays in the Picture, but he just went into an absolute attack. I was already a bit fragile about the film, but I wasn’t expecting that! By the way, what did I say earlier about using the Rage Against the Machine track? David was right; he was right to attack it. He hated the animation and there might be something said there. Then he referenced a PBS documentary on a similar subject that was done in the most dry, academic approach imaginable. I was shocked because this was David Bowie! He didn’t appreciate the audacity of what I did! Then his assistant said “What’s your favourite Bowie album?” and, having just been stung,, I looked at David and said, “Well, to be totally honest David, I can’t say I’ve really appreciated anything you’ve done since 1983.” He looked at me and never took his eyes off me and went, “Touché.”

Now, you got the real answer to “Hallo Spaceboy.” For the first time, I will tell the full continuation of that story. David passes and I work out the rights agreements for the film. I start doing my deep dive into Bowie and guess what? I love ’95 era, Outside, Earthling, and so on. Heathen is probably my favourite album if I didn’t say it earlier, or Reality. I love those albums. I don’t want to say I was guilt-ridden, because David didn’t give a shit what my opinion was in that room at that time. And it was clearly said in a playful, brazen, flippant way. But I went into the project going, “I’m going to correct the mythology about David and really validate his latter-year work because I’ve come to greatly appreciate what he did.” The reason that specific validation isn’t in the narrative of the film is that so much of the film deals with his investment in his work and how he doesn’t have room for other areas. When he meets Iman, the investment in his work changes, reaches a plateau, and it stays on that plateau until the end of his life.

For anyone wondering why the film ends where it ends, I wasn’t trying to avoid the latter years. I remember screening to Jesse Moss really early. He made a comment to me like “It’s starting to feel like it’s going ‘and now he’s doing this album,’ that genre trap that so many adventurous non-fiction films end up falling into at some point. Moonage Daydream is designed so that if you’re a Bowie expert, you’re filling in the holes.

POV: If you’re not a Bowie expert, you’re going to get lost here, in the best possible way. You’re going to get lost in the way that the music is going to take you on the journey, not the chronology is going to take you on the journey. Through montage, a “montage daydream,” you’re going to have different songs of different eras speak to one another as his own narration guides you through this journey.

BM: Everybody’s going to get their own Bowie from it. If you’re a Bowie expert, you bring all of that knowledge to the table and it’s filling in the blanks. If you know nothing about Bowie, you’re not watching this film going, but what about Iggy Pop?

The film was made for three different audiences very consciously. First, there’s the hardcore fan. For them, there’s all of the Easter eggs and all of the never-before-seen footage. Then there’s the fan that is helped by seeing it all as a singular journey in two hours as opposed to pieces here and there. You start to contextualize albums and eras that you’re familiar with in a new way.

It’s not about David Jones; it’s about you, the viewer. You could say that’s a pretentious comment, but it is what it is, and what the film was designed to be. By not loading it with information, it creates something more experiential, which allows and invites projection. You’re not being sandwiched into something.

First, there’s the hardcore fan. For them, there’s all of the Easter eggs and all of the never-before-seen footage. Finally, for those who don’t know Bowie, it’s definitely intended to be about them. Here’s what David’s saying about how to navigate life, and hopefully it can find resonance with you. Giving life lessons isn’t necessarily the thing one expects in a music documentary.

The really hardcore are looking for inventory, they’re not looking to fill in the narrative journey. They want to know how many seconds of Earl’s Court are on the film. Then there’s the fan that is helped by seeing it all as a singular journey in two hours as opposed to pieces here and there. You start to contextualize albums and eras that you’re familiar with in a new way. Finally, for those who don’t know Bowie, it’s definitely intended to be about them. Here’s what David’s saying about how to navigate life, and hopefully it can find resonance with you. Giving life lessons isn’t necessarily the thing one expects in a music documentary.

POV: A testament? One thing that I pointed out as breaking your rules was the overt inclusion of Iman. You’ve pointed out that it was such as transformative mode at that time of his life, and it is just a few minutes within those few hours, but that time where the film becomes essentially biographical in a way that it had shied away from.

BM: What I say is that he needed Iman. There’s really nothing about the relationship that’s real, she’s just a symbol. But yes, you’re right, I had a rule going into it which I broke on three occasions to not have biographical information. However, I ultimately came to the conclusion that with the addition of a limited amount of biographical information, it would not only better contextualize David’s arc, but I think it allows the audience to project their own stories in an empathetic and engaging way. David’s story about his parents, it’s his mom and dad, it’s not very specific….

POV: But being married to a supermodel is not simply “I found the love of my life”, That is another level of mythos. We all have moms and dads—we do not all later in life marry a supermodel. This is what I’m saying:there’s something more grandiose and tabloidy about that moment than anything else in the film.

BM: Well, she happens to be world-renowned. To be honest, I requested to use imagery in that section of Iman and David that they took of each other, so that it would feel as authentic and intimate as possible. Instead, we went with the Bruce Webber pictures. But I don’t view that moment the way that you do. I relate to that in finding my wife. My wife helped me get to where I am now. I wouldn’t have been able to do Bowie without having that.

POV: But we’re not talking about the other wife, we’re not talking about the other children.

BM: Here’s where I’m going to push back on you I included Iman, but not because she’s a celebrity. I wasn’t trying to exploit the tabloid aspect. You know that I took a lot of flak in Montage of Heck (2015) for not putting David Grohl in. I didn’t use him because I wanted one person to represent each aspect of Kurt’s life, and Krist Novoselic filled that. Other people would have used Grohl because of the celebrity quota. One lesson I learned from David about making art and making films was that art isn’t perfect. It’s imperfect. Those introductions of his family and Iman make the film better. They lead me to have to entertain questions like, “Why didn’t you mention Iggy? Why didn’t you mention Lou Reed?” That’s a waste of real estate. You already know that thing.

POV: I’m not saying that what you did was tabloidy. I’m just saying that so many of the other things felt universal in a sense. Many of us have siblings, we all have parents, etc., The way you incorporate Iman feels heightened.

BM: There are no bad pictures of Iman. You have no idea how hard I looked.

POV: It’s not about her image. How David talks about Iman is different from how he talks about his art, different from how he talks about his music. Suddenly, he changes. Which I get is very interesting in the context of what you’re saying, but I’m saying we get, for , a brief moment, a different David in that portion of the film.

BM: For sure, you get the David who’s going to be that guy for the next 25 years.

POV: And that was not as clear for me on first viewing as it is now in conversation with you.

BM: Here’s the thing: The film is like a Rorschach test. People are going to read different things into it. Obviously, the film is going to confuse some people. My job between now and the time that the film comes out is to prepare the audience to approach the film like they’re bamboo, and just allow it to blow them this way and that way. If you enter it rigidly, and try to demand an explanation, u, it’s not going to be there.

POV: What is on the page for a film like this?

BM: For eight months after I finished screening all the research, there was nothing on the page other than philosophies or theories. I would write about ideas. I would write about chaos theory. I would write about things that can’t be scripted, to be honest. I was really just trying to buy time to figure out how I would do it. I was collating and collecting things and I had at some point landed on chaos and transience as the throughline of the film. I mean, that’s not hard to land on when David Bowie straight up says it!

It’s the subject he was most excited and eager to engage on, especially in the latter part of the interviews as the internet broke and we entered an era of true chaos. He was thriving off it.

All of my movies, as unconventional as I would like to think they are, are fairly concrete cause-and-effect narratives, with a very straight line, with a lot of salad dressing poured on top. I was a little baffled and confused and honestly did not think I was the right person for the Bowie job but we were too deep into the process for me to walk off the film. Ultimately, I took a page from David’s book, and after spending eight months in my office banging my head against the wall I went to Albuquerque. I’m going to quote David from my film, I knew I had to “change my environment.” On a whim, I woke up one morning, went to Albuquerque on an Amtrak with all of my binders of research, got into a little cabin, and was not coming out until I cracked this thing.

I did this sort of game or exercise. I said, “I’m going to pick three songs from every album going back to the ’67 self-titled David Bowie album that relate in one way, shape, or form in my broadest definition of chaos, transience, gender fluidity, cut-up process, transit, transitioning, but would allow there to be a cohesive thread.

POV: You made a playlist.

BM: I made a playlist. I got a little concerned because it was coming up in chronological order, so I was trying to shuffle it up. Eventually I made it a little more linear that way, but I would say that by the time I got back to L.A. I had cracked it and figured out these different passages.

The Berlin era speaks for itself, it’s probably the easiest one in terms of transience, but coming out of that, the next period of his life, where he does Ashes to Ashes and Elephant Man, I turned that into the transit section where there’s no home. In fact, I was originally rooted to this song “Move On” instead of “DJ” to kick off that section.

The song “Move On” has some really odd production. It wasn’t until I got to the sound mix and I could hear it on the big speakers and I kept wondering why every time this song comes on, I want to do this, but I’m not. I needed that punch of “DJ”. I’m now realizing that “DJ” probably doesn’t fit into the playlist, but I’ll justify it now: I needed that energy at that moment, and we were very deep in the edit.

POV: So that’s how one does it. One goes away, one makes a playlist, one makes a movie.

BM: That was the real breaking point, yeah.

POV: You obviously gained full access to the library. With that, were there any specific restrictions?

BM: When I first acquired the rights, I sat down with Bill [Zysplat] in New York and the one caveat he said to me was “Listen, David’s not here to authorize the film. We’re going to approve it and we’re going to give you access to everything. But it’s not ‘David Bowie on David Bowie,’ it’s ‘Brett Morgen on David Bowie.’ You need to make this your own.” I had final cut and was given access to everything within their vault. When the film was finished they loved it, but they said there were one or two sections that they would prefer I didn’t go in to, namely, his family. But there was never a request or a thought or a suggestion to change anything.

POV: You gained access to a lot of the stems, or the isolated tracks. It’s one thing to have access to an entire library, and that’s gotta be overwhelming.

BM: I really wanted to work with music stems in an IMAX arena for two reasons. One, to try to create a 360-degree, immersive space instead of a two-track stereo frequency, almost reproducing the experience I had as a kid at the Laserium with Pink Floyd. Forgive me, because I know you’re Canadian, I’m not a fan of Cirque de Soleil. However, I saw the Beatles’ Love show because I’m a big Beatles fan and, while some Beatles traditionalists may think it’s sacrilege, I thought it was exhilarating. I loved the commentary and the new associations that were being created. When I started going through Bowie’s catalogue, there were musical elements that I wanted to reference for thematic purposes, but the lyrical content of a particular song may not have any value to me or the same for the musical component. Breaking up the stems gave me the opportunity to use those elements to conjure up memories. With “Life on Mars,” when they hear those isolated piano notes, it does a certain thing.

When we did Jane at the Hollywood Bowl with a live orchestra [based on Phillip Glass’ score], it was the first time and probably the only time in my life I’ll get to stand where the conductor stands when we were doing the rehearsals. It was the most mind-blowing experience, because from that one vantage point, you turn your head a little bit this way and you hear the strings, you turn your head a little bit that way and you hear the woodwinds. To be honest, you won’t get this in stereo or 5.1 the way you do in Atmos or IMAX. One guitarist is over there, and the other is over there, and somehow it’s all working. We’re going to send the sounds up into the ceiling for a solo, and now it’s going to go to the back left of the room, and now it’s in our laps. It was just wild, man. It was exciting to enter the mix with the understanding that we weren’t using the ceiling and the surrounds for accents, but we were actually starting there.

That was a challenge for Paul Massey, a fellow Toronto native, in his illustrious 40-year career. Everything he’s ever done is emanating from the front of the room. It was a tug of war in trying to move it into the room. Fortunately, Paul understands that if you don’t have the right sound system, and most theatres don’t, you can’t do certain things because it’s going to fall apart. We went aggressive on the IMAX and the Atmos, a little less on the 7.1, we’re actually mixing the 5.1 next week, and we’re keeping it fairly conservative, knowing that’s probably going to be the one used in most cinemas. We can’t control the room, so we are going to keep it focused on making sure the important stuff is heard.

POV: You show up in Cannes, you’re dancing on the red carpet, acting like a lunatic, you sit down in this black tie environment, and finally the film is shown to anaudience. What did it feel like?

BM: It’s hard for me to talk. You’ve got to give me a second. [Pauses for over a minute, crying silently.]

This film was very difficult to do. It ended up being the most challenging job I’ve ever worked on, both creatively and from a production standpoint. I had this enormous weight that was lifted when I arrived in Cannes, from the moment I got there.

At a certain point ,we were cut off financially. It wasn’t so much a burden that it was David Bowie and I wanted to get it right, I just wanted to get the film done for years. It just was elusive; it was really challenging. After 15 months of post, probably six months longer than we were ever supposed to do, and the sound mix and everything, I arrived feeling like I had left no stone unturned. I had this enormous weight that was lifted when I arrived in Cannes. I have always shown up at my premieres wrecked with nerves, and I had no nerves showing up because I felt that I had had the opportunity to do it on my terms the way I wanted to.

POV: You danced on the red carpet to “Let’s Dance.”.

BM: They cue me to go up the red carpet and they’re playing the traditional theme, Camille Saint-Saëns “Carnival Animals,” which is one of my favourite pieces of music. The Kid played at the smaller Buñuel theatre, but the 2300+ seat Grand Lumière is heaven, you know? I was not expecting in that moment that they would play “Let’s Dance” and I just let it go. When I was in the edit room, or in the sound stage, and that song came pon, that’s kind of what I would do. My wife likes to say I’m a method director, I feel the whole thing very intensely. In that moment, with no forethought, I danced, something I haven’t done since Bar Mitzvahs if it wasn’t obvious from seeing me.

POV: I was in a room of all those people giving a standing ovation to you dancing before you entered the room.

BM: Cannes is for cinephiles like us, it’s the dream. I had the luxury and privilege of spending five years working on one piece of film. It afforded me the opportunity to really do whatever it took, and that is a wonderful thing. That doesn’t happen that often.

POV: The fact that I got to share it with you is one of my absolute pleasures.

BM: And by the way, bro, my wife was like “Who is that guy? You didn’t even hug me!” I got so much shit at home about that, Jason. She’s like, “What the hell was that? Who did you just run over in the middle of a standing ovation?” I was like, “You don’t understand, I was just living my dream.” All of a sudden, you’re there wearing a rock concert t-shirt. You were the most recognizable person in that room and I don’t know if it’s a faux pas to say, but I only go out into the film world every few years when I have a film to put out. Through that experience over the years, you meet people. You want to share those experiences with people you know, whether they like the film or not. Thank you for sharing the moment.