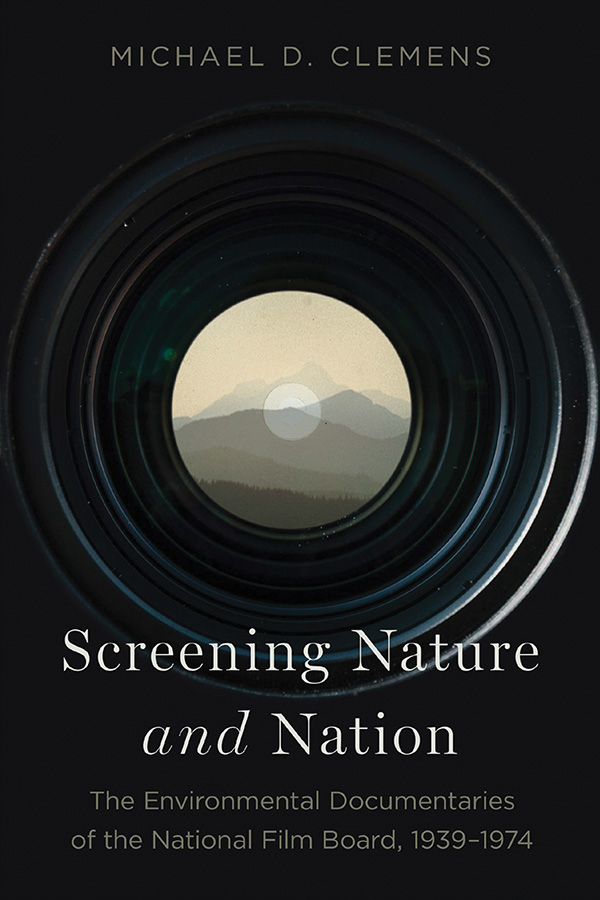

The history of environmentalism in Canada is also the history of the National Film Board of Canada. In the new book Screening Nature and Nation: The Environmental Documentaries of the National Film Board, 1939-1974, Michael D. Clemens astutely traces both the history and the evolution of environmental filmmaking in Canada. Clemens considers four key facets of NFB history regarding environmental documentary: the early years of state messaging, the romanticization of the North, the rise of environmentalism, and the Challenge for Change years. These periods reflect how filmmaking at the Board reveals the role of environmental iconography in Canadian nation-building, as well as the adaptations of filmmakers’ perspectives on the role of echoing the nation state. The trajectory of NFB eco docs goes hand-in-hand with the evolution of documentary form itself, as Clemens observes through phases of the Board’s development and of the role of publicly funded cinema.

The history of environmentalism in Canada is also the history of the National Film Board of Canada. In the new book Screening Nature and Nation: The Environmental Documentaries of the National Film Board, 1939-1974, Michael D. Clemens astutely traces both the history and the evolution of environmental filmmaking in Canada. Clemens considers four key facets of NFB history regarding environmental documentary: the early years of state messaging, the romanticization of the North, the rise of environmentalism, and the Challenge for Change years. These periods reflect how filmmaking at the Board reveals the role of environmental iconography in Canadian nation-building, as well as the adaptations of filmmakers’ perspectives on the role of echoing the nation state. The trajectory of NFB eco docs goes hand-in-hand with the evolution of documentary form itself, as Clemens observes through phases of the Board’s development and of the role of publicly funded cinema.

Windbreaks on the Prairies, Evelyn Cherry, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Art or Propaganda?

The first chapter, “Filming Like a State,” considers the foundational years of the NFB in which documentaries mostly propagated state messaging. Clemens situates NFB environmental filmmaking within the state messaging of the war years, particularly the “Canada Carries On” series. By focusing on key films and figures at the Board during this period, as he does with close textual and contextual analysis in each chapter, Clemens shows how NFB docs reflected and shaped Canadians’ relationship with the environment. In the years following World War II, these films championed the prosperity of the Canadian landscape. Images of a bountiful land awaiting harvest were frequent, as was the expansion of territory within the national ethos.

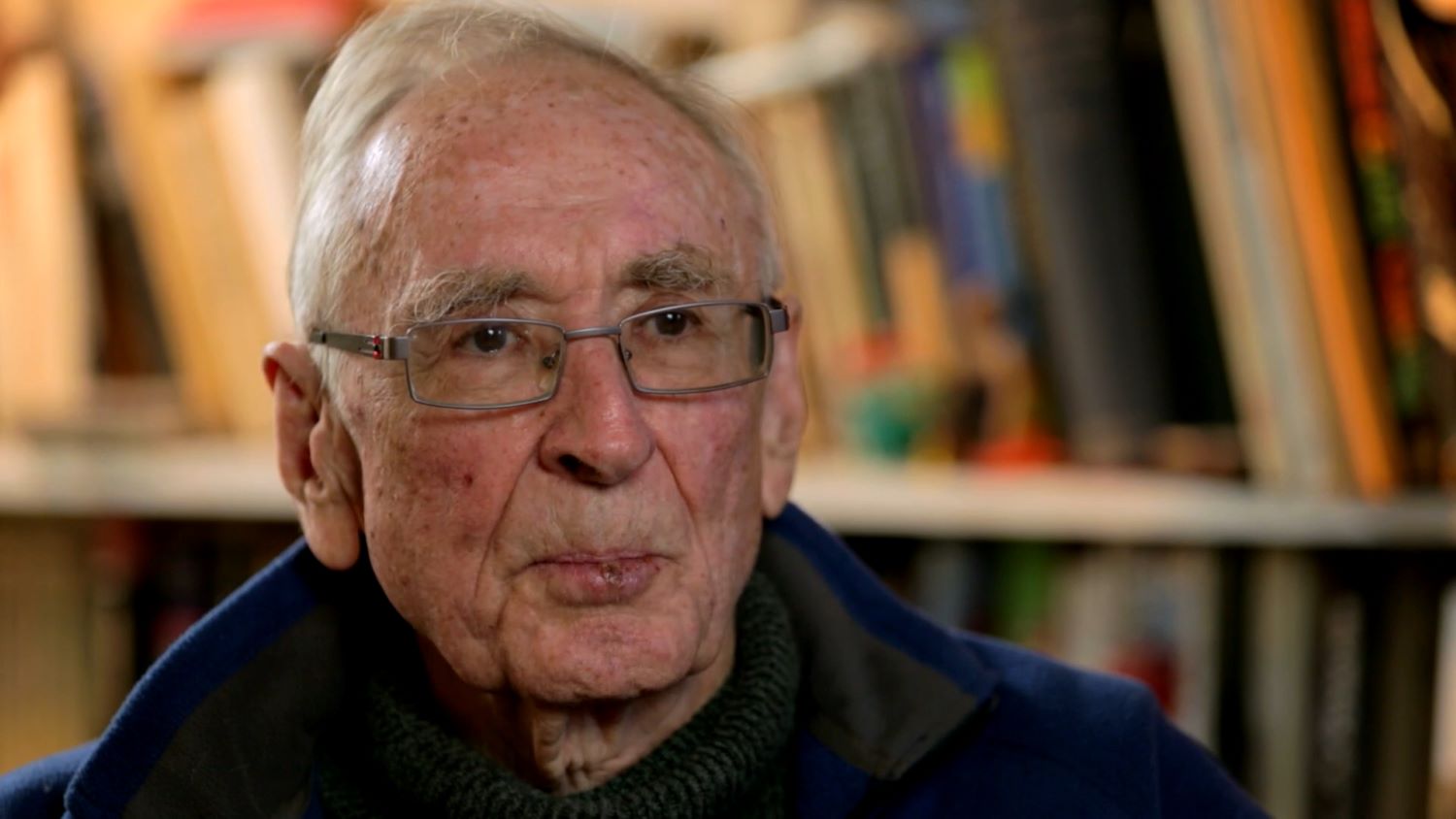

However, Clemens observes that the wartime filmmaking bled into environmental documentary. Filmmakers like Evelyn Spice Cherry employed symbolism to evoke images of progress and togetherness, using elements like tractors to conjure ideas of freedom and prosperity through technology. However, close readings of Cherry’s films such as the artfully composed Windbreaks on the Prairies (1943) and the comparatively didactic Five Steps to Easy Farm Living (1945) illustrate the creative tensions that filmmakers navigated while delivering government messaging. Clemens sees filmmakers like Cherry nevertheless refining a signature voice—an auteur of the prairie/natural resource doc—by developing distinct techniques. For example, he notes how Cherry used relatively generic characters. Her films have a universal sentiment, as far as the limited notion of “Canadianness” at the time said, by seemingly reflecting characters who could be from any place and of any social standing.

Land of the Long Day, Douglas Wilkinson, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The Idea of the North

If the NFB films of the wartime years reflect a relationship between harvesting the land and national growth, then Clemens sees a competing viewpoint in another stream of environmental docs. In chapter two, “Visions of the North,” Clemens unpacks a series of films that perpetuate a romantic view of Canadian wilderness. Clemens sees a relationship between these films and the paintings of the Group of Seven, which offer picturesque views of the North as an ambiguous place of untamed wilderness. He argues that the North is a particularly complicated Canadian symbol. There are at least three different representations of the North: “as a wilderness sublime, as an ‘exotic’ other, and as a modern space governed by the state.”

Screening Nature and Nation doesn’t shy away from confronting the complicated history of representation. Clemens considers the films of Laura Boulton, who documented Inuit life in films such as Arctic Hunters (1944) and Eskimo Arts and Crafts (1943). Screening Nature and Nation observes how these films strive to present objective portraits of the North, but ultimately frame their subjects from a settler perspective in stories of survival amid a landscape of unforgiving hardship. “In Boulton’s films,” Clemens writes, “the Inuit are practically indistinguishable from their environment.”

The romantic viewpoint of the North therefore carries a colonial gaze and implication, which appears in films from the era. Doug Wilkinson, for example, presents the North as “an exotic landscape inhabited by ‘primitive Eskimos’.” Even in some of the most popular NFB films then and now, like Wilkinson’s How to Build an Igloo (1949) and Land of the Long Day (1952), Clemens observes the complicated romance with the North.

In Land of the Long Day, for example, Clemens notes the fabrication of a narwhal hunt that was directed specifically to create a visceral thrill. Clemens notes that the hunters used a harpoon instead of their habitual rifles at the directors’ request. These films therefore employ tropes of outdated ethnographic filmmaking. Moreover, their romanticized viewpoints suggest the North ultimately serves the interest of the South. Clemens argues that such representation divorces the Inuit from modernization schemes of the state, and minimizes Canadians’ responsibility to the land.

Poisons, Pests and People, Larry Gosnell, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Eras of Change

Clemens nevertheless sees NFB films about the North as reflecting larger creative tensions in documentary as creators displayed a willingness to challenge the perceive neutrality of the camera. In chapter three, “The Call of the Wild,” and chapter four, “Challenge for Change,” Screening Nature and Nation explores two of the NFB’s most significant developments: Unit B and the Candid Eye series and Challenge for Change.

Clemens observes in chapter three how the Unit B era embraced subjectivity. Docs had a point of view and weren’t afraid to use them, and Clemens argues that the birth of environmentalism has an important link with NFB films from this era. As Carson notes, docs like Larry Gosnell’s Poison, Pests, and People (1960) pre-dated the publication of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring (1962) with its message about the connection between pesticides, the devastation of animals, and the detection of cancer in humans. Clemens’ close reading of Poison, Pests, and People, including a chilling deleted scene, illustrates how filmmakers like Gosnell shifted the medium from sharing the state’s message to sounding the alarms.

Particularly strong is the most thorough reading of a film in Screening Nature and Nation when Clemens examines Cree Hunters of the Mistassini (1974). This study of the landmark Challenge for Change doc observes how the environmental films considered throughout the book demonstrate the growing sophistication of NFB filmmakers. The book credits the doc directed by Boyce Richardson and Tony Ianzelo for situating the environmental movement within a de-colonial frame. Clemens positions Cree Hunters of the Mistassini as a key work of Challenge for Change as it was emblematic of the kind of films to which the movement aspired by giving voice to people from communities marginalized within Canada. His reading of the film demonstrates how it offered the Cree hunters’ perspective and gave them a platform to resist the settler state. Moreover, Clemens argues that the Cree are ultimately co-authors of the film.

Clemens sees Cree Hunters of the Mistassini as an “unromantic portrait of living off the land.” It mostly counters the binary of idealization and hardship observed in the earlier documentaries about the North. The film also offers a productive portrait of the relationship between humans, plants, and non-human animals by presenting them all as dynamic beings. However, Clemens admits that the doc isn’t perfect and says it offers a depiction of the “ecological Indian.” (Recall that the Keep America Beautiful commercial with the Indigenous figure crying over trash came out in 1970.) Screening Nature and Nation ends by showing the evolution of environmental cinema at the NFB as Cree Hunters observes the adaptability of the Cree and the relationship between ecological devastation and colonialism.

Cree Hunters of Mistassini, Boyce Richardson & Tony Ianzelo, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Conclusion

Through careful analysis of formative documentaries from the National Film Board of Canada, Clemens makes clear the relationship between active filmmaking and active viewing. As the earlier works from the Board propagated to a passive audience a state message about expansionism in a land ripe for cultivation, the NFB gave shrewd filmmakers a platform to shape environmentalism and, ultimately, the form of documentary itself. Clemens sees even in the most didactic years of the Board moments in which filmmakers innovated with film form, whether they were exploring the relationship between documentary and drama or challenging the perceived objectivity of the camera’s gaze.

Screening Nature and Nation captures the complicated yet invaluable role the National Film Board of Canada played in shaping the nation’s relationship to the natural environment. Many of Clemens’ observations anticipate works that emerged from the Board following the Challenge for Change years: from If You Love this Planet to Angry Inuk, the NFB’s role in reflecting our responsibility to the planet continues to evolve. This book captures the necessary foundation.