Trust a Canadian to make a documentary even if he’s miles from home. Montreal born and bred Jeremy Elkin identified with New York as a youth and, in particular, the amazing street culture that emerged there in the Eighties. Montreal had a small skateboarding scene—it’s hard to build up one in the snowy downtown—and a slightly bigger hip hop culture. For Elkin, travelling down to New York to skate in the Eighties and be part of the exciting club environment must have been the best thing he’d ever experienced. Now, 25 years later, he’s made a doc that evokes the scene that made him into the artist he is, All the Streets are Silent, a heartfelt adieu to the true funky NYC before Giuliani gentrified it.

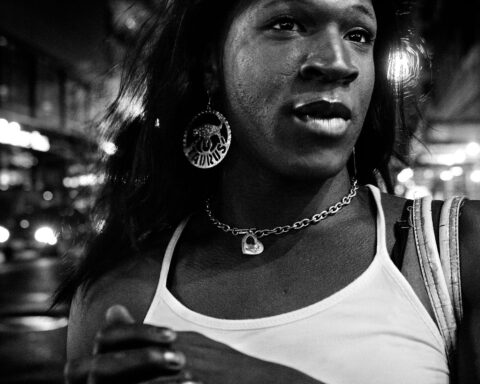

Elkin’s doc covers the crucial period when rock and soul music ceased to be relevant, ceding truly popular music over to hip hop and rap. While the new music was being heard in clubs and the neighbourhoods, on turntables and in live performances, skateboarding in New York took off on the streets of Queens and Brooklyn. Both the musicians and the boarders meshed with the hot new clothes, dances and graffiti to create a vibrant, if often violent, scene for youths in the city. Elkin recognizes the simultaneous reaction of people from every genre—skateboarders, dressmakers, turntablists, poets, producers, musicians, promoters, painters—who wanted to make something new while gangs in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens were fighting each other and the city was nearly bankrupt.

The simultaneity of New York having great skateboarders and hip-hop artists in the late Seventies and Eighties wasn’t missed by people at that time. Early videos show how well skateboarders, those magnificent athletes, move—if only unconsciously—to the rhythms of hip-hop. Throughout Elkin’s doc, people speak about the Zoo York mixtape (1997), which magnificently captured how well the styles meshed. All the Streets are Silent inherits the feel of Zoo York and offers it to a far bigger audience. (I recommend that you see Zoo York on YouTube it’s free, and gives you a great sense of what Elkin is recreating in the film.)

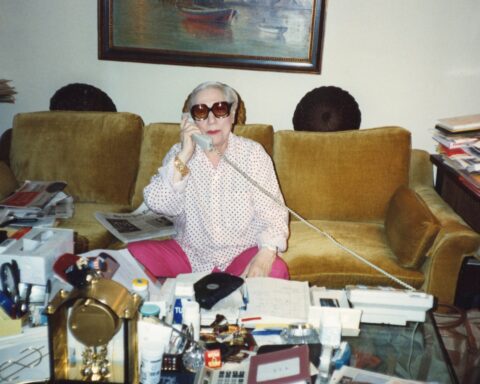

To make a great doc that evokes the recent past, you need two things: wonderful visuals from the era and access to the people still alive to tell the tale. Elkin has both, which allows him to slowly savour what happened over the course of a decade. Manhattanites and even some people from Queens and Brooklyn weren’t convinced about hip-hop scenesters and skateboarders until Club Mars opened on 10th Avenue and 13th Street in the early Eighties. It was a nowhere area then; now it’s an expensive district near the Whitney Museum and the High Line. Mars’s operator Yuki Watanabe, interviewed now and shown in archival footage, produced different shows on each floor—and all were exciting. Moby was the first DJ hired at Mars, and in his interviews, he talks of others who were just as good, particularly DJ Clark Kent. The early Eighties saw other clubs opening up with more and more attention paid to the musicians and skateboarders, who wanted to do their thing and be paid for it. New companies formed that wanted to work with them and that trend, which has made some wealthy, continues today.

Throughout the film, the beauty of skateboarding is given the rapt attention it deserves. We see the boarders executing near-impossible moves leaping up ten steps to get to the top of a subway landing and then maneuvering magnificently through the tight dank urban scene. Elkin loves them and the doc helps to immortalize the skaters: Harold Hunter, Keith Hufnagel, Jefferson Pang and others. They give us an instinctive and visceral take on the city at that time, as do hip-hop giants like Run DMC and Busta Rhymes. All are in the film.

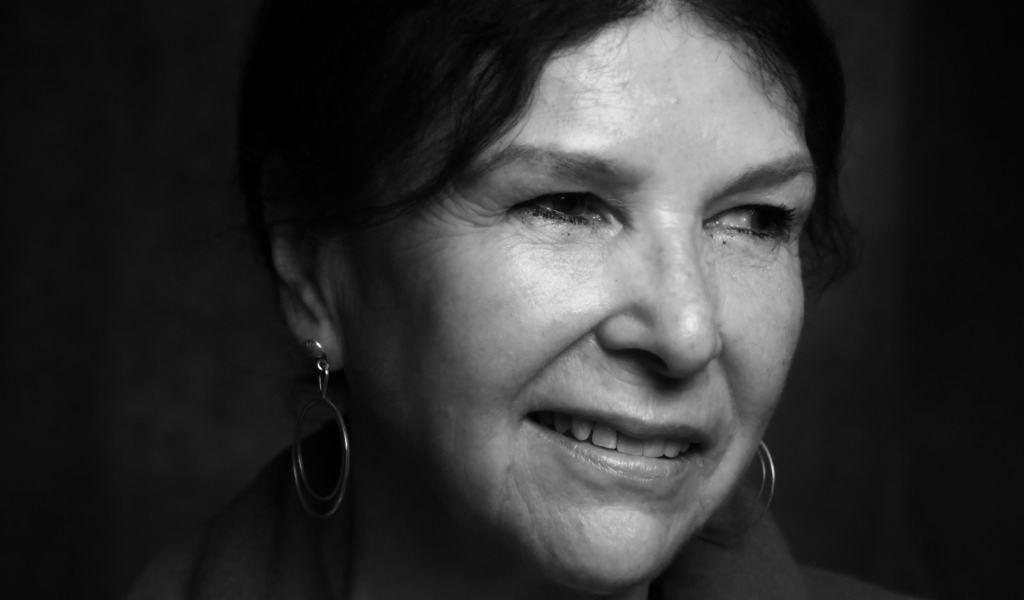

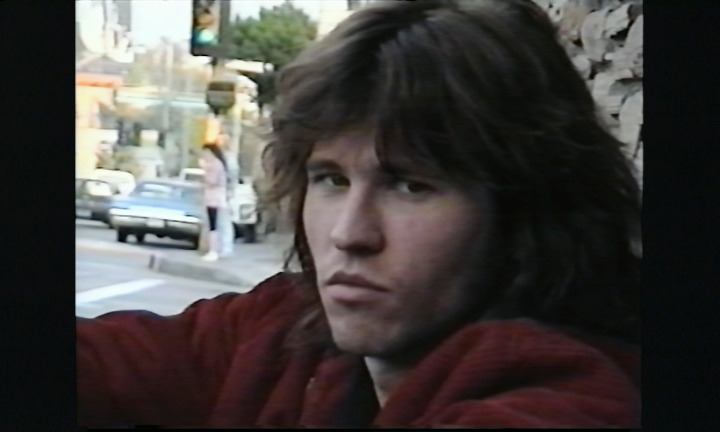

Even the coolest scene needs a kick-start to get widely known. In the early Nineties, the great photographer Larry Clark appeared in lower Manhattan. He took pictures and hung out with the young misfits who littered downtown, partying, skating, taking drugs, having sex, pulling scams. He showed them his masterpiece, the photobook Tulsa, and they were persuaded that the cowboys back there were like them, and that Clark could take beautiful photos and make a fine film. With their participation, and the collaboration of a gifted young artist named Harmony Korine, he made Kids, a spectacular hit that made NYC’s scene into a place that the hipsters worldwide wanted to come to and enjoy. Rosario Dawson, one of the stars of Kids, has gone on to fashion a great career and she’s on hand in the doc to give context to the boarders and the scene she knew so well back then.

Elkin’s documentary points out that capitalism, at least on a small scale, isn’t a bad thing. Thanks to skateboard makers, magazine publishers, video artists, independent producers and fashion designers, something miraculous happened. Those crazy kids from the Eighties? If they haven’t died, we see them finally cut into a pie that is finally offering them money. Good on them. They deserve it.

What about New York? Are the streets truly silent? Has gentrification destroyed the city that never sleeps?

My opinion?

New York will never die and youth will always be radical and ornery. All the Streets are Silent brilliantly tells us about one amazing time in the city—and if hip-hop and skateboarding interest you, it’s a great idea to see the film.

Me? I endorse Elkin but will always be in thrall of the NYC I knew in my youth, beautifully captured in Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller’s doo-wop rock’n’roll classic “The Boy from New York City” and the lyrics “he’s so cute in his mohair suit and he keeps his pockets full of spending loot.” Yes, it rhymes, too, and reeks of the same streets, but at a different time.

All the Streets Are Silent streams via Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema beginning July 22.