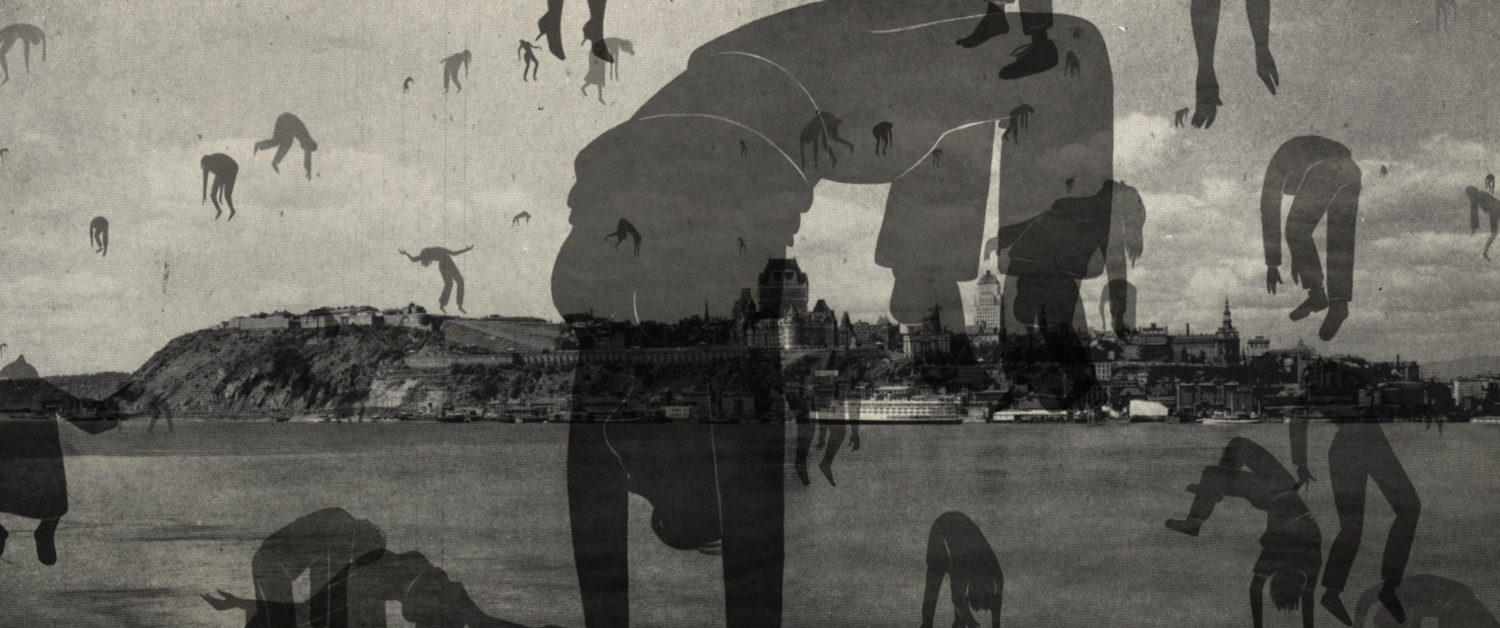

Misha and the Wolves is one of those films that one must watch on faith that it’ll be great. Its story is one of astonishing deception. Director Sam Hobkinson and his collaborators have crafted a work of non-fiction that plays like a detective mystery or thriller. By using the mechanisms of fiction filmmaking to tease out the truth, the result is a fascinating and engaging work that balances between being broadly entertaining while never shying away from the deep and dark truths being exposed.

Hobkinson has decades of experience with documentary and true-story filmmaking, including National Geographic’s The Hunt for the Boston Bombers (2013), or the crime documentary The Kleptocrats (2018). His latest film has both journalistic integrity and formalistic swagger, resulting in a film that’s challenging and compelling on many levels.

Giving a run down about what transpires on screen undercuts much of what makes Misha and the Wolves work, but suffice it to say, it’s a film that joins a long and lustrous line of films that twist our expectations and use the very form of filmmaking to unsettle our preconceptions and prejudices. This is a factual film about fabulizing, and while some of its overt cinematic elements may frustrate viewers who prefer what’s supposedly a more “pure” form of documentary, those open to this kind of hybridization will find plenty to admire, and plenty more questions and complexities that are raised beyond the overt storyline.

POV spoke to the director prior to the film’s virtual premiere at Sundance 2021.

POV: Jason Gorber

SH: Sam Hobkinson

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: Congratulations on the film.

SH: You’ve seen it, I’m assuming?

POV: I am not one of those people who do interviews before experiencing the film.

SH: I apologize for asking but now that you’ve seen the film, you’ll understand it’s quite difficult to talk about it until you’ve seen it! There’s one journalist who will remain nameless who didn’t bother.

POV: I am very sorry on behalf of everybody who claims to do my job. At any rate, let’s start right at the beginning. How did the story come to you?

SH: The story came to me when I was reading a newspaper article six years ago. I came across in this British newspaper a story about an ongoing case in the Massachusetts courts to do with a Holocaust memoir that had turned out not to be true. The court case rambled on for years and years, actually past where we go to in the film. At a much later point, I tracked the story back and researched a little bit and quickly realized that it was quite an amazing story. I could immediately envision a documentary where I could tell a story about storytelling, which would explore themes of memory and history, one that would start as an historical documentary but become very quickly a psychological thriller.

POV: You have many avenues you could have gone down with this narrative. You take one that is extremely engaging and extremely compelling, and as you say it becomes a psychological thriller. How did you narrow that storyline to avoid getting lost in the weeds?

SH: I wanted it to be a character-driven thriller, and that choice narrowed down a lot of avenues. As you’ve said, there are a lot of themes in the film, but I wanted them as subtext. I wanted to create a battle of wills, a moral maze. I wanted a film that immersed the viewer in the same experiences as the participants in the story. It was very important for me to peel back layers of truth as the film proceeded and treat the viewer, I suppose, to the same twists and turns as the participants in the story. When you approach it like that you have to bury and suppress the thematic elements. They come out of the story more organically. We did not have a cast of academics and journalists discussing the subject, instead allowing the participants to unfold this story naturally.

POV: Your film makes explicit certain moments of recreation, which some non-fiction purists continue to chafe at. As a filmmaker, do you worry about such formalistic concerns?

SH: It’s tricky to discuss in these interviews. I prefer not to talk about it as it’s quite an important spoiler to hold back. That’s one of the moments when the audience finds themselves in the same position as the participants in the story, as it were. But what I can say is that this is a documentary about untruth and fabrication. So when you make a documentary about untruth, you’re inverting the form in a way. We’re supposed to be making true stories, but when it’s a true story of a lie, then everything is inverted. I do think the documentary form has moved on quite significantly in the last 20 years to a point where people come to these films understanding that they will use every tool in the armory to tell a story. Ultimately, when a film or a story resolves within a documentary, it can be dangerous if the viewer goes away uncertain as to which elements were truthful or fictionalized. If you’re creating a film that puts the audience in an experiential environment, then I think anything is fair game now. Yet that might be controversial.

POV: Were there specific films that you looked at to get this tone correct?

SH: Bart Layton’s The Imposter is a film I love, and also Stories We Tell by Sarah Polley, which is about family secrets. They’re both stories about storytelling. And there’s the great F For Fake by Orson Welles.

POV: When conducting the interviews, particularly with the survivor, our central guide, I think it would have been very easy to portray them, for lack of a better word, as overly sympathetic, as if you needed to hammer the good from bad. And yet, there’s such grace and subtlety and humanity experienced by her in the film, in all its contradictions. Was that startling to you, that there was less word anger and righteousness with the reactions from some of these people?

SH: I should start by saying I didn’t start out to make a Holocaust documentary. As I said, when I found the story, this was a story about storytelling. As it progressed, I realized that I was in fact making a Holocaust documentary. I was just making a different kind—a postmodern one, which is less about the terrible events themselves than it is about the cultural shadow they cast. This is in part about the Holocaust industry, if you like—the journalism, the memoirs, the documentary films and everything that goes with it. That became quite fascinating to me.

At the same time, we discovered this character, Evelyn Handel, herself a hidden child from Brussels, Belgium who is a Holocaust survivor. She became part of the detective team that helped uncover the truth behind Misha’s tales. Evelyn is an incredibly wonderful woman and very thoughtful, very honest with her experiences. After interviewing her, we realized that she would play a greater role in the film than we’d previously thought. What’s key is that she is what I call “the center of good” of the film. She has no ulterior motive. She entered the story almost as a favour to a friend and out of curiosity. She’d done a lot of genealogical research into her own past, and she discovered who she really was in the same way that she discovered who Misha really wasn’t. It seemed fitting that she was the one who had the last word in the film. I thought it was a very difficult film to end because there’s a lot of bad blood between very opinionated people and we wanted to make a balanced film. We wanted the audience to make up their own minds about who was a victim and who was a villain in the story.

We tried to finish the film in many ways, deciding who was going to have the last word, and it was very difficult. Ultimately we found this great bit of Evelyn’s interview where I asked her what she feels about Misha now. She struggles to articulate herself, and this is a very articulate woman. Sometimes these moments in documentaries are really telling where people don’t really answer a question. Normally you’ll pick the bits of an interview where people answer a question concisely and clearly, but actually, in this case, she struggled to articulate herself. She chose a few words, and then actually said, “no, that’s the wrong word.” For me, it was this moment of this woman who’d gone through so much pain in her life and was trying to articulate herself about how she feels about what Misha did. That summed up the whole story, and it actually summed up how I felt about Misha.

POV: How did you deal with the question of truth and fiction? You of course did so within the structure of your film, but did the experience of delving into this tale reshape the way that you see stories are told? Do you have more or less sympathy for those who were fooled?

SH: It was a big interest to me, and has been in other films, in terms of the question of how and why we believe the things we believe to be true. What’s fascinating in this case is that the story Misha was telling was pretty out there or over-the-top on many levels, but what fascinated was she that was telling it from the perspective of being a Holocaust survivor. So it was less to do with whether the story seemed believable and more to do with the fact that it was very difficult to challenge it given that she was saying she had gone through this terrible experience in her past. As the radio host who appears in the film says, far be it for me to challenge what she’s been through. I think it’s interesting, and that’s ultimately what the success of her lie was based on. She was hiding behind something that was very difficult, emotionally difficult. to question.

POV: It leaves us in a really complicated place, which is what great films should do. It makes us question things at a point in time where many people are completely aghast about people questioning such things, on whatever level and from whomever they are. You have people again who are literally weaponizing lies, people who are talking about alternative facts, and then you have others who, as a counterreaction say we are obliged to believe all apparent victims. How do you navigate those things as a filmmaker and as an individual?

SH: As an individual, it’s very difficult, isn’t it? I find fascinating the breaking down of news channels to channels of news and channels of opinion. In the UK at the moment, there are new TV networks that are more opinion channels than news channels. Here we have a great public broadcaster, the BBC, who you feel you should turn to for unbiased, balanced reporting of the facts. But I think, as an individual, it is becoming more and more difficult to know who and what to trust. When you get these films funded, commissioned, and you go in to pitch stuff, the first question everyone asks is “why now?” Misha’s story is something that happened a while ago, but it seemed fitting to be telling the story now in the era of fake news, alternative facts, etc. I just read Malcolm Gladwell’s book Talking to Strangers, which has a whole bit in it about how human beings default to truth. It’s our first default when someone tells us something to believe it to be true. The skeptics are actually the outliers. Most people will believe people, he argues, and that’s important for human society to exist. If we’re all skeptical, then where does empathy lie? Where does charity lie? It’s fascinating to consider. With our film, we wanted to be fair to people who had believed this story. It was quite difficult to get people to talk on camera about this because they’d been drawn in – be they friends, neighbours or even people who’d interviewed her on radio. This is certainly not about making people seem foolish, because I think clearly a lot of people were drawn in by this.

POV: Who made money off the uncovering of the lie, versus those who made money off the lie itself?

SH: Maybe a few journalists? What’s interesting about this story is that big money was involved, but there was never big money received. It’s a classic example when you talk about the “Holocaust industry” or genre. There was big money mooted when the story was going to be optioned by Disney and when Oprah Winfrey’s book club was involved. The figure was $22 million in the court settlement, but that was all to do with the value of the property rather than any money made. What’s interesting is that very little money was made along the way by the book or by the revealing of the lie. We wanted to be transparent and self-referential in the sense that we are another in a long line of people exploiting this story. There are various devices used in the film in which we show our transparency, and it was important to be honest and clear about that.

POV: I am suggesting that there’s often so much more attention to the allegations and so little paid to the corrections. Your film actually allows us to go in and see the correction, to see the power of the correction, but also be cautious about the sway of the original narrative.

SH: There was attention paid to this story because it is stranger than fiction. That’s probably why it has very good currency and every time it comes up, be it in a court case or a documentary or whatever.

POV: To Gladwell’s point, not only are we people who assume truth, we’re also creatures who inevitably look for narrative. We try to contextualize things into stories. If the story itself is compelling, that compulsion as it were becomes for us empirically true. If you could talk about the challenges of telling the story in a way that teased but didn’t cause roadblocks, that told the story with respect, but did so in a way that’s entertaining and engaging?

SH: Where do I start? [Laughs] In a sense, this idea of peeling back layers of truth gave us something that might propel an audience through a narrative. That was important to me from the outset. Also, there’s this idea of shifty genre, I suppose. I wanted it to start like an historical documentary and then at some point shift gear into a psychological thriller and then become something else. Avoiding getting bogged down in the weeds is always a tricky one. I think it was important to let the audience make up their own minds as we went along, so not to get too bogged down in over analysis as things go forward, and to allow revelation to propel the story. When this begins, the audience knows very little. A lot of documentaries try and frontload a lot of information and almost tell you where you’re going and then go there. We wanted to do something that was much more like the structure of a scripted narrative, really, which allowed us to navigate clearly the story.

POV: That structure and trust in an audience is for me often a fundamental difference between a television documentary and a cinematic documentary. I’m very spoiler averse at the best of times, but I believe so much of the richness of a film of this nature is to go in knowing as little as possible.

SH: I would say that as well. Read as little as possible, and certainly don’t read Google while you’re watching!

POV: Which leads to the obvious question: Could her story work when everyone can search the Internet, or would her lies be different and more sophisticated?

SH: That’s a really interesting question. Deborah Dwork, the Holocaust historian who we interviewed in the film, talked quite a lot about that and it didn’t make it into the film. I asked her that question and she thought the lies wouldn’t hold up. This story is based in the mid ’90s. People actually knew a lot less about the Holocaust. Facts are much easier checked now by any armchair detective.

POV: And yet, we have ability now with video to actually replace someone’s face and have them speak words that are not their own, so the lies just get different and more complicated.

SH: A different kind of deception, I guess.

POV: That’ll be a topic for your sequel!

Misha and the Wolves premiered at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. and has its Canadian premiere at Hot Docs.

Visit the POV Hot Docs Hub for more coverage from this year’s festival!