“The mystery in Kane is largely fake…”

— Pauline Kael, Raising Kane, 1971, on the “shallow masterpiece” Citizen Kane.

“We Hanky Panky men have always been with you.”

— Orson Welles, F for Fake.

F for Fake, first released in 1973, is Orson Welles’ last major film, a docudrama about art forger Elmyr de Hory, and Clifford Irving, author of a hoax biography of Howard Hughes. It has been combed over and admired by Welles fans as an expression of his own thoughts about the art of cinema. But there is one aspect which has been glossed over, or explained away, which is the depiction of women in the film.

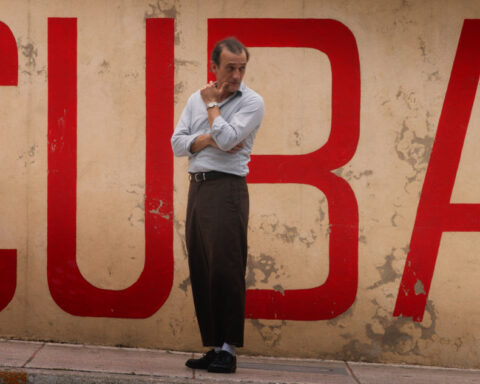

Oja Kodar, Welles’ companion, is a prominent subject of ogling both at the beginning and end of the film, a kind of upfront objectification that would be awkward to explain to contemporary first-year cinema students. Maybe they did things differently in those days, but even that, along with the fact that Kodar is credited as a co-director and writer of the film, can’t entirely make that awkwardness disappear. None of this is intended to spoil the intrigues in this most personal film by one of cinema’s great creative personalities. F for Fake certainly holds up to repeat viewings, exploring the ideas of artifice, authorship, expertise and cinematic sleight-of-hand. Welles appears in the film, often in a magician’s cape and broad-brimmed hat, in his 1970s persona as the twinkling talk show bon vivant, though he’s a deceptively unreliable narrator. As Welles said in an interview a decade later, “Everything in that film was a trick.”

Watching the film on repeat viewings you admire the lively, jigsaw editing, and how often characters seem to be interacting but, in fact, may have been shot at different times and places. There are self-reflexive visits to the editing room, in which Welles rewinds and reconstructs the story.

F for Fake divides into three sections. There’s a ten-minute overture, in which Welles introduces himself as the magician-host, and his theme of trickery, as well as the principal characters in his story, including Kodar and the story’s two leads, de Hory and Irving. That’s followed by a roughly hour-long documentary about de Hory and Irving, with digressions on Welles’ personal history and views on art.

Some of the footage was originally shot for a television documentary by director François Reichenbach, which Welles had agreed to help edit. During the editing, Irving was exposed as the creator of a fake autobiography of Howard Hughes, and his story became part of the expanded feature film with its new director, Welles.

During the film, Welles reviews his career and identifies himself as a fabricator, another word for artist. There are musings on the role of “fake experts” in validating forgeries, meditations on a Kipling poem which considers the Devil to be the first art critic, and a panegyric to Chartres Cathedral, “the premier work of man in the whole Western world and it’s without a signature.”

And all this brings us back to the work of women in F for Fake. The third section features Oja Kodar and her supposed youthful affair with Pablo Picasso.

The ending is the answer to a sequence at the film’s beginning, when Kodar, described as “bait,” is first seen walking through the streets of Rome as men nearly break their necks to ogle her. Originally shot for an abortive 1969 CBS special called “Orson’s Bag,” the sequence seems gratuitous but is offered as a taste of the trickery to follow.

Another woman who found her way in front of Welles’ cameras was Edith Irving, Clifford Irving’s glamorous artist wife, who took cheques intended for Howard Hughes and deposited them in a Swiss bank under the name Helga Hughes. Yet another was Nina van Pallandt, the folk singer who was having a secret affair with Clifford Irving while he was supposedly visiting Howard Hughes, and later testified against him in court. As a topless photo of van Pallandt is shown, Welles describes her as “that morsel plucked from [Elmyr’s] list of prison visitors.”

The final (fictional) story, which is credited to Kodar and initially told as a true story, brings us back to Oja and Picasso. Welles describes how Picasso (depicted in various wild-eyed photographs) was frenzied to distraction by sequences of the young woman walking in various revealing outfits. It culminates when she goes to his studio and appears in a series of discreetly nude scenes.

Intones Welles: “I can’t tell you what happened in there but Picasso was a fast worker, by which I mean to say, you understand, that the results of this encounter were, to say the least of it, extremely fruitful. Figs sweetened on the trees, grapes burst into ripeness on the vines, large portraits of Miss Oja Kodar were born under that virile brush.”

To reframe this without the burbling innuendo, women are “bait,” “morsels” and ripe fruit, who arouse and deceive men and cause them to create art and forgeries to impress them. The title F for Fake (it was Oja Kodar’s suggestion) might well have stood for Female. Welles expressed the idea more directly in an interview with David Frost: “If there hadn’t been women we’d still be squatting in a cave eating raw meat, because we made civilization in order to impress our girl friends.”

Lest this be excused as the mores of the times, the ethics of ogling was a contentious subject around the time F for Fake was released. In 1972, John Berger’s revelatory BBC television series and accompanying book, Ways of Seeing, described how the history of art involved rich men putting their mistresses on display in art. Laura Mulvey’s influential essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” which posited the “male gaze” theory, was published in 1975, before the American release of F for Fake.

Welles is the epitome of the American auteur director, setting the template of the male genius filmmaker, and enshrining a system where women consistently direct fewer than ten percent of top-grossing movies. As the critic B. Ruby Rich noted in a damning essay in The Guardian, back in 2003: “As the very embodiment of the brilliant writer-director, Welles inaugurated a category that had a Gents Only sign nailed to its door from the beginning,” setting the template for Quentin Tarantinos, Lars Von Triers, Darren Aronofskys and other boy wonders to follow.

The Wellesian legacy, Rich says, is signified by “cleverness, grandiosity, no use for women. A killer instinct for the sucker punch. A pathological need for attention that makes behind the camera insufficient without add-ons (screenwriter, on-screen talent, whatever). Up-to-the-minute technology and a strong aesthetics of style.”

Pauline Kael raised some of these same criticisms in Welles’ lifetime in her 1971 New Yorker essay Raising Kane, which attempted to denigrate his roles as producer, director, co-writer and star of Citizen Kane. Kael attacked Welles as a symbol of the cult of auteurism, or the “genius-artist-director, the schoolboy hero—the man who did it all.” Her attack on Welles echoed her earlier critique of auteurism in her 1963 Film Quarterly essay “Circles and Squares,” in which she dismissed the theory as “an attempt by adult males to justify staying with the small range of experience of their boyhood and adolescence.”

Welles refuted many of Kael’s claims through his friend Peter Bogdanovich in an article, The Kane Mutiny, in the October 1972 issue of Esquire, while he was working on F for Fake. His last completed film is also often considered a riposte to Kael, as an example of the “fake expert.”

From a contemporary perspective, it’s possible to see F for Fake not just as a celebration of Welles’ life and cinema but as a manifesto from a (very unstable) male genius.

The Australian comic Hannah Gadsby, whose stand-up routine explores the misogynist legacy of Pablo Picasso—the genius with whom Welles pretended to share a mistress—is well worth listening to on this subject. In an Australian interview in early 2018, “This guy [Picasso] was sick in the head and he abused women—and nobody ever [mentions it]; it just gets absorbed into his story and this marvellous idea [of Picasso]. And Donald Trump is the logical inclusion—in my head. Here’s a guy who thinks he can just grab pussy because he can—and he can, because of celebrity. It’s the cult of the artist, and it’s the cult of the celebrity—they’re the same thing.”

The importance of F for Fake is not what it says about Donald Trump. As a deliberately mischievous work of art, Welles’ film invites us to consider its implicit value system. We can be in awe of the skills of the magician but should also wonder why it’s always the women who get sawed in half or are made to disappear.

F for Fake is available on home video.

Welles’ final film, The Other Side of the Wind, debuts on Netflix November 2 along with Morgan Neville’s new Welles documentary They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead.