Some naysayers might call 2021 an off year for the Toronto International Film Festival. However, the TIFF Docs programme illustrates how 2021 was, artistically, one of the better years for the festival in recent memory. TIFF Docs had exciting films from filmmakers both established and emerging. Docs captivated us with gripping stories, iconic characters, and innovations in film form. The strength of the TIFF Docs line-up extends to the overall official selection, although this stream proved one area where the festival could still secure significant world premieres. There’s no denying that a virtual and/or hybrid festival cannot replicate the live experience, but despite some bumps in the execution of its digital platform, TIFF mostly delivered in its second pandemic-era event. It’s hard to complain about logistics when the films themselves were so strong.

Any shortcomings at TIFF, moreover, can hardly be blamed upon the festival proper. Rather, the restrictive access, geo-blocking of titles (not at all bad for the documentaries, but the fact that Canadian films were blocked to Canadian press and industry is flat-out nuts), and absence of interview opportunities were all the result of sales agents, distributors, and publicists who haven’t caught up with pandemic era festivalling as well as the festivals have. Most years, critics can interview anyone they please with film reps happily facilitating access to anyone from the director to the caterer. This year, however, many reps were virtually lobbying for media not to cover their films during the festival. In most cases, folks openly treated TIFF as an opportunity to take names for exposure during future Oscar campaigns. Journalists at TIFF 2021 couldn’t even bank coverage for future use, a standard practice that lets everyone maximize on the event, even with filmmakers who made the trip to Toronto.

The latter point is a growing concern. Documentaries especially benefit from active engagement, and nowhere is that opportunity more apparent than festivals. Shutting down conversations, rather than inviting them, is not in the spirit of documentary. However, filmmakers shouldn’t pay for their handlers’ standoffishness, so this report will focus on the positive: the docs themselves.

Attica‘s High Bar

Thanks to some pre-festival access and an unhealthy amount of coffee, I was able to see all the documentaries at TIFF except for the two that screened as Special Events. Triumph Rock & Roll Machine and Memory Box: 9/11, for me, were simply casualties of the front-loaded schedule. (Read Jason Gorber’s review of Triumph here.) Overall, the slimmed-down festival made it relatively easy to take in the 14 films screening in TIFF Docs, along with others peppered in the Galas, Special Presentations, and Wavelengths programmes.

The TIFF Docs programme curated by Thom Powers set a high bar for itself on opening night with the world premiere of Stanley Nelson’s Attica. The film capped off a strong year for Nelson, who received Hot Docs’ Outstanding Achievement Award this spring. Attica might be Nelson’s best work yet for its visceral examination of the 1971 prison uprising that sparked an unprecedented bloodbath of police brutality.

Attica assembles many of the survivors to correct the narrative scored in official records. The surviving inmates speak of human rights abuses in vivid details that contextualise the revolt. Moreover, the dramatic pauses with which the interviewees inflect their testimony accentuates the riveting suspense of the drama that plays out in the archival elements.

Drawing upon an extensive range of archives, Nelson’s skill as both a researcher and visual storyteller unfolds the saga with unnerving suspense. Knowing when to cut from a black-and-white still to a colour photograph that reveals the prison grounds saturated in blood, Nelson’s doc presents a compelling account of an event that resonates strongly amid the cases of police violence and anti-Black racism of today.

Confronting Police Brutality and Systemic Racism

Attica proved a smart opener for the programme as TIFF Docs followed Nelson’s powerful film with a doc that recounted an event that narrowly avoided repeating the tragedy of Attica. Stefan Forbes’ explosive Hold Your Fire is a visceral and provocative examination of a 1973 hostage crisis in New York. The film recounts the ordeal from various viewpoints to explore the standoff between four armed men who held up a sporting goods store and the trigger-happy cops who were itching to take them down. Forbes’ film smartly draws upon the competing viewpoints and memories to illustrate how survivors of traumatic events remember them differently, as the hostages and eventual hostage negotiator (whose presence makes the standoff especially significant) either confirm of refute the duelling accounts by the armed men on both sides of the story. Forbes’ film leaves one in complete suspense until the final credits roll.

More compelling, though, is the lasting prejudice that Forbes witnesses in the cops’ accounts. Decades later, they still recall the standoff through a white gaze. Rhetoric about thugs and gangsters, as well as dehumanizing language not worth repeating, illustrate the mindset that brought the standoff so close to the brink of violence. This gripping film probes the police mentality that continues to perpetuate injustice.

Music Docs, Ahoy!

Two of TIFF’s most widely publicized films came from the quartet of music docs at the fest. Jagged, Alison Klayman’s portrait of Canadian rocker Alanis Morissette, screened as a Gala, but its star was notably absent. (Although, having reached out to cover the film early, I know that this wasn’t a surprise.) Morissette’s unexpected denunciation of Jagged overshadowed the film’s premiere and invited conversations about the fine line between documentary and PR that’s becoming easily blurred.

As a celebration of music, however, Jagged offers an entertaining dive on rock history that unpacks the album’s significance within the context of its production and reception. While one might be surprised that Morissette disliked Klayman’s unwaveringly celebratory portrait of her groundbreaking album Jagged Little Pill, one can also appreciate the subject’s frustration that Klayman’s films mentions significant and sensational aspects of Morissette’s story—sexual abuse, for example—without giving them the attention they deserve.

Also celebratory, but clearly appreciated by its subject, was Dave Wooley and David Heilbroner’s Dionne Warwick doc Don’t Make Me Over. The doc is a straightforward account of Warwick’s career that explores her breakthrough as a Black artist in a segregated America, but Warwick captivates as a raconteur. Her tale is one of putting a platform to good use and uplifting others during one’s own upward climb. The film pays special attention to her role as an LGBTQ rights activist and observes how her own fight to enjoy her rightful space inspired her to fight for others—a point that continues to this day.

As one of few major stars in attendance, Warwick worked Toronto in a way that demonstrated her drive to be a guiding light for others. As the recipient of a special honour during the TIFF Tribute Awards, Warwick’s scrappy passion helped TIFF 2021 feel like a regular year for the festival whenever she was in the spotlight.

Even More Music Docs

The conventional, if consistently enjoyable, design of Don’t Make Me Over may have felt doubly familiar thanks to Barry Avrich’s Oscar Peterson: Black + White screening in the TIFF Docs section. Both films are perfectly enjoyable docs: toe-tapping celebrations of great artists and important accounts of the hard work Warwick and Peterson laid for future Black artists, and other underrepresented voices, to transform audiences through the power of music. Avrich’s film draws upon a chorus of Canadian and international artists who pay tribute to Peterson amid the doc’s mix of interviews and archive. The films prove that, even in a festival, one can find comfort in familiarity.

Alternatively, the presence of conventional celebratory portraits greatly benefitted Penny Lane and her brilliant Listening to Kenny G. The doc, which comprises part of the same music doc series as Jagged, is further proof that Lane is one of the most original voices in documentary. Her take on jazz saxophonist Kenny G makes an unconventional leap for music docs. Rather than offer a straightforward account of his highs and lows, Lane assembles Kenny G, his fans, and his haters for an engrossingly entertaining debate about musical taste and who has the right to be a critic. Kenny G proves a winning doc character as he gamely goes along for Lane’s challenge. What transpires is a hilarious and consistently engaging dialogue about the fine line between artistic integrity and popularity and the subjective factors that distinguish good art from bad. (Read our interview with Penny Lane here.)

A Top Chef and a Sour Taste

A highlight of the TIFF Docs programme, similarly, was easily Betsy West and Julie Cohen’s delightful Julia Child doc. Julia surpasses the duo’s Oscar-nominated Ruth Bader Ginsburg doc RBG with its affectionate portrait of the woman who revolutionized American kitchens through French cooking. This scrumptiously crafted film is prepared as meticulously as Child’s boeuf bourguignon is. Julia salutes Child’s determined fight to empower women by giving them the tools they need to excel in the kitchens, but it’s also a beautiful love story enhanced by an impressive range of photographs taken by Child’s husband, Paul.

However, the food is the true star of Julia as West and Cohen offer mouth-watering sequences that capture the recreation of Child’s signature dishes through macro photography. These images take food porn to another level—not through their yummy decadence, but through their illustration of what it means to craft a meal with care. Julia thoroughly examines the role that the dining room table plays in domestic life and how the question of who gets a seat at the table has implications that extend to all facets of life. Julia brought a dish worthy of a Michelin Star to TIFF Docs. (Read our interview with West and Cohen here.)

Less palatable for this critic, however, was the widely acclaimed Beba. Rebeca Huntt’s ode to herself is an odd contrast to the portraits of Child and Warwick. The arty and angry visual essay sees the filmmaker chronicle her fight to assert her space as a young Black woman in America. While Huntt has fair motivation, this self-portrait of her coming-of-age is a tale of raising oneself by stepping on the backs of others. The cinematography by Sophie Stieglitz is striking, but it can’t mask Beba’s biting cruelty and underlying ugliness.

Huntt proves needlessly confrontational and thrives by inflicting pain upon her friends and family members to build her sense of self. This factor proves unwatchable as Huntt turns her fury against her Venezuelan mother, often reducing her to tears, with tirades of vehement anti-Latinx racism. Huntt obviously grows confident throughout the eight-year odyssey she documents, especially as noted in the poetic voiceover, but there isn’t a sense that she learns from the painful experiences she orchestrates. The film’s a reminder that one must afford respect to others before demanding it from them. Beba is the self-indulgent narcissism of contemporary selfie culture taken to extremes.

Questions of Identity

Other TIFF Docs selections that grabbled with representation, space, identity, and memory proved more productive. Gian Cassini’s Comala, for one, excelled as a work of self-examination. The filmmaker examines his late and estranged father’s career as a hitman for the Mexican drug cartels. While Cassini confronts members of his own family to force some painful conversations, there’s a palpable sense that the experience is therapeutic for all—and mutually respectful. The filmmaker draws upon the conflicted memories of his family members to reflect upon his own self-worth, sense of self, and identity as a man who chooses love over hate. Comala resonates a healing contemplation of the measure of a man.

Similarly, questions of identity and belonging fuel Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s Flee, which repeated its “best of the fest” distinction in Toronto after wowing me at Sundance. This animated film rewards multiple viewings. It’s an exceptionally moving account of a young gay man escaping Afghanistan and then experiencing a life in which he’s always on the run as he and his family navigate the liminal spaces in Russia, and again with his boyfriend as an adult. Flee transports audiences through the nerve-wracking experience of fleeing as Amin narrates his story in a therapeutic confessional and Rasmussen imagines the story through deft animation. It’s a harrowing, transformative, and liberating experience as Amin confronts his rootlessness. Flee marks the best use of animation ever in a feature documentary—besting its obvious predecessor Waltz with Bashir—as it brilliantly conveys subjective experience, staying true to Amin’s version of events while respecting his right to safety and anonymity. Films like Flee can save lives. (Subscribe to read more about Flee and an interview with Jonas Poher Rasmussen in our fall/winter issue.)

The theme of fleeing also propels the gripping docu-thriller The Devil’s Drivers. This riveting film years in the making by Mohammed Abugeth and Daniel Carsenty takes audiences through white-knuckler rides from Palestine to Israel via a secret taxi service. Employing elements of a thriller while giving pause to the gross human rights abuses faced by Palestinians who simply want to provide for their families, The Devil’s Drivers features some of the most extraordinary footage of the festival.

Eco Docs

TIFF Docs brought two of the biggest names in documentary, Liz Garbus and Eva Orner, with a pair of environmental films that were among the programme’s highlights. Garbus’s Becoming Cousteau offers a rollicking portrait of the explorer, inventor, and filmmaker Jacques-Yves Cousteau. The film, which was the only TIFF Docs selection geo-blocked to attendees on the digital platform (across North America no less) didn’t quite find the audience it deserved. (Barring the film from digital access is a silly point when one considers that much of the material is footage that Cousteau shot for television in the 1960s and ’70s.) Those who saw it, however, can attest that Becoming Cousteau is a handsomely produced all-archival odyssey through the subject’s adventures.

With voiceover by Vincent Cassel reading Cousteau’s letters, the film recounts how the man conquered the deep sea. His many inventions and experimental deep dives, which proved fatal for some of his colleagues, build a rich foundation for the film’s exploration of Cousteau’s skill as a filmmaker and eventually as an environmental activist. The man in the red beanie affords Garbus some wonderful material to work with as the doc observes life on Cousteau’s beloved boat Calypso and the family that joined him for much of his life’s work. The film is especially touching as it sees the aging Cousteau have a change of heart about his work, some of which was financed by research for resource extraction, and even comes to see the brutal imagery from his Oscar and Palme d’Or winning film The Silent World as out of touch with contemporary efforts to save the planet. The film is an effective portrait of one man’s ability to inspire the world, but also be inspired by it.

Orner’s Burning, on the other hand, is an incendiary study of the wildfires that ravaged Australia in 2019-2020. The doc finds its fire as Orner makes a compelling case for change. She looks back at the events that preceded, predicted, and precipitated the massive wildfires that incinerated 59 million acres of the Australian landscape, taking incalculable tolls on the wildlife and devastating many families whose homes were engulfed by the flames.

Angry eco docs can alienate a viewer with their fiery tone, but the unabashed rage that comes through both the footage and the interviews with Australians strikes the right tone. It’s impossible to watch Burning and not feel one’s pulse flicker as Orner recounts the ineptitude of Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who notoriously went on vacation in Hawaii while his country literally burned. Even more outrageous is the film’s look at Australia’s response to COVID recovery that doubles down on fossil fuels and shows that the politicians like Morrison cannot be swayed by obvious evidence for climate change. Orner finds hope, however, in the story of youth activists who recognize the need for immediate change. Burning is an invigorating call to action that could not be more urgent.

Similarly, TIFF Docs brought a Canadian story to the environmental fight with Heather Hatch’s potent Wochiigii Lo: End of Peace. The doc unpacks the economically impractical and environmentally disastrous construction of the Site C dam along British Columbia’s Peace River. Haida director Hatch draws upon various perspectives from First Nations members to convey the history contained in the land that will be ruined by the dam’s completion. The visually compelling film draws notable power from the landscape to underscore the beauty and heritage contained within the neighbouring valleys on which many of the interviewees’ ancestors walked—and upon which their children never will when the damage is done.

Experiments in Form

The doc side of TIFF also shook things up with several films that explored their subjects through active engagement with cinematic form. (Including the above-mentioned Flee.) Bianca Stigter’s haunting Three Minutes – A Lengthening repurposes just over 180 seconds of found footage shot in 1938 Poland to consider the weight of absence. Sifting through the images repeatedly and considering their every detail for clues about the stories preserved within the frame, Stigter’s film is a profound examination of lives lost during the Holocaust, as well as the records of that have been scrubbed from the Earth. It’s a thoughtful reassertion of existence. (Read more about the film in our interview with Stigter.)

Alternatively, Italian filmmakers Pietro Marcello, Francesco Munzi, and Alice Rohrwacher capture the present and look forward with Futura. The film, which screened in TIFF’s Wavelengths programme, offered a sumptuously shot portrait of youth. The filmmakers pay homage to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1964 travelogue Love Encounters by touring the country and asking young people for their thoughts about the future. The answers are an expected range of silliness and cynicism during early encounters, but production resumes after COVID hits and the students begin to respond with renewed vigour. Like Burning, Futura finds a hopeful spark for the future by observing an energized generation hungry for change.

Also screening in Wavelengths and bringing to the TIFF docs selection a portrait of personal and political awakening was Payal Kapadia’s A Night of Knowing Nothing. This provocative essay film, which won the l’Œil d’Or at Cannes, easily marks Kapadia as a significant voice to watch. Her debut feature is among the most formally innovative and deeply philosophical works to be found anywhere in the festival line-up. A Night of Knowing Nothing poetically considers the loss of innocence as Kapadia constructs a narrative through “found” letters that outline the courtship of a young couple. The relationship morphs as the political climate of India changes, and the young woman at the heart of the film undergoes an eye-opening transformation as students rise up to protest the rising Hindu nationalism and ongoing caste discrimination. The doc features some truly damning footage of police brutality, which appears as Kapadia dials back her formal collage and lets the images play in stark, unsettling real-time.

Celebrating Docs

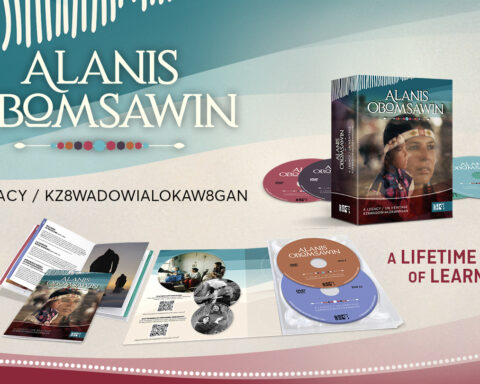

No survey of the TIFF docs would be complete without mentioning the notable retrospective of Alanis Obomsawin’s work that made the festival especially doc-friendly. The “Celebrating Alanis” retrospective curated by Jason Ryle featured some of Obomsawin’s most significant works, like Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Existence, as well as some of her lesser knows short docs. The series also screened her latest doc, the short Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair, which pays tribute to the man who chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. The timely doc asks Canadians to listen to Indigenous perspectives as the nation moves forward with reconciliation. There are painful moments in the film, but Obomsawin’s doc fits with her latest body of work about the rights of Indigenous children as it emphasizes how young people will carry the light forward. As with some of the TIFF Docs selections, Obomsawin’s film illustrates how optimism is a necessary political force in 2021.

Finally, celebration is due to the People’s Choice Award winner for documentary, The Rescue, by Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin. This gripping tale is on par with their work in Free Solo, but where the dizzying peaks of the mountain movie inspire awe, the dark recesses of Thai caves in The Rescue deliver heart-pounding suspense. The filmmakers show incredible compassion for their subjects as they recount the 2018 rescue mission that saved a dozen young soccer players and their coach from an unwieldy cave at the onset of monsoon season. Using thrilling recreations, an exceptionally well-crafted archival core, and emotionally engaged interviews, The Rescue is a truly cinematic adventure. Vasarhelyi and Chin won the Oscar for Free Solo after wowing the crowd at TIFF, and if the enthusiasm of the local audience is any indication, they could easily repeat their feat.