The documentary scene has exploded with stories of truth and justice since #MeToo rocked the world in October 2017. However, director Eva Orner brings a tale of a rapist who preyed on women and got away with it in Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator. The film, which launches on Netflix today after debuting at the Toronto International Film Festival in September, offers what Orner calls a “pre-#MeToo story told in a post-#MeToo world” as she assembles a chorus of women who share their experiences with hot yoga guru Bikram Choudhury. Despite losing a civil case and skipping town to avoid owning up to his deeds, Choudhury has yet to face criminal trial for the numerous allegations that include rape and sexual misconduct. The film offers a record that succeeds in holding the predator to account when the justice system fails survivors.

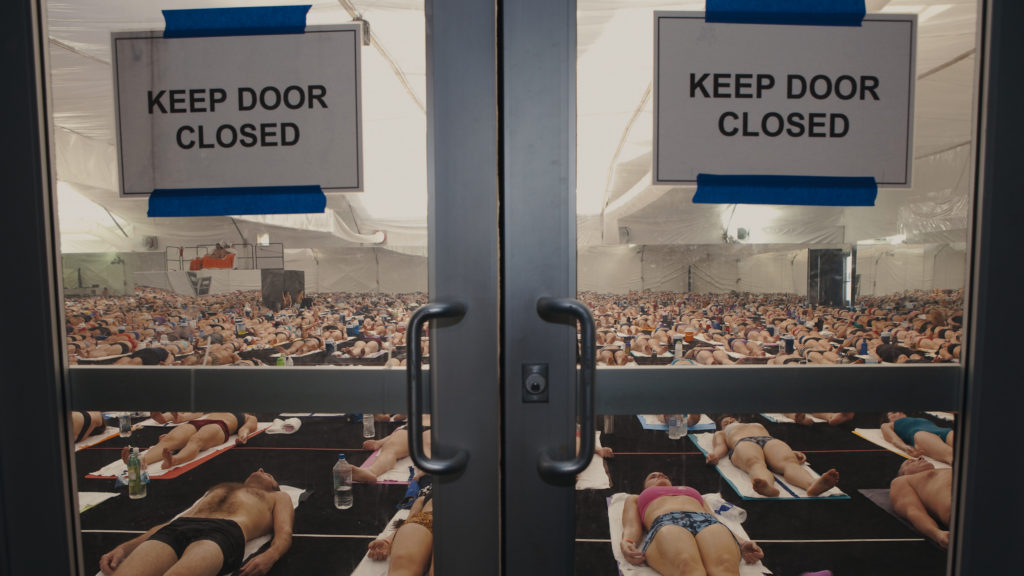

Unlike Harvey Weinstein, though, Choudhury can’t get his cover story straight. Orner’s film, while dark and urgent, is often wickedly funny as it combs through the astonishingly range of archival material, including tapes of Choudhury’s depositions. Despite being a serial liar, Choudhury is a terrible storyteller. Orner’s film knocks him off the yogi pedestal on which he built his hot yoga empire, often wearing nothing but a Speedo bathing suit and a Rolex watch. But one can also see how participants at his studios were easily taken in as Orner and the interviewees portray a man who seduced his clients with hopes and aspirations to better their lives, only to violate them in the most intimate ways.

The film marks Orner’s fourth documentary as a director following the riveting exposé Chasing Asylum (Hot Docs 2016) and the stories of Middle East conflict Out of Iraq (2016) and The Network (2013, on top of a prolific career as a producer that climaxed in an Oscar win for 2007’s Taxi to the Dark Side, directed by Alex Gibney. Bikram marks Orner’s style as one of the doggedly determined documentarian as her films tell urgent stories buoyed by hard-to-get images that hold guilty parties accountable for their crimes.

POV met up with Orner at the Toronto International Film Festival in September to discuss Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator, pursuing this story in a post-#MeToo world, and enjoying the chase of the hard get. (And while it reads somewhat dark, we assure readers that it was quite a spirited and lively conversation!)

POV: Pat Mullen

EO: Eva Orner

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: What was the time period for the production in relation to #MeToo?

EO: It was brought to me around June 2017, so it came before #MeToo [which broke in October 2017]. Then as we were developing it, obviously more and more was happening. It’s a pre-#MeToo story in a post-#MeToo world. I think that’s the interesting take. The women in the film who came out are so strong and so brave. They risked everything, but they also kind of lost everything. At the end of the day, they didn’t get the result they wanted because he got away with it.

When you watch it in a post-#MeToo world, it’s a bit of a dire warning for how easy it is for powerful men to get away with things. I feel very positive about what’s happened in the last couple of years, but there’s still a lot of work to do.

POV: What was the process of gathering the speakers for the film?

EO: It’s the same with any documentary. You get into a subject and then you start contacting people, talking to people, and building trust. A lot of people are very hesitant and maybe say no. You have to make them comfortable and make them believe in you. As you get one, maybe another one comes on. They were very suspicious and concerned, rightly, but once they came on, they were committed. I think they’ve all had a positive and cathartic experience. A lot of them want to close this chapter because it’s gone on for a long time and it’s very heartbreaking since they never got justice.

POV: What sort of dynamic did that create in the interviews?

EO: It’s completely different, but it’s a little bit like Jeffrey Epstein killing himself. A lot of women were saying, “I wanted to look him in the eye in a courtroom.” In the film, Larissa, the woman with the blue hair, says, “I wanted him to acknowledge what he’s done.” They feel he got away with it.

POV: Do they, or do you, feel that there’s at least some justice now that there is a record for other people to see?

EO: That’s why they’ve done this film. They want their stories told. They want people to stop doing the yoga. They want people to stop calling Bikram Studios by a rapist’s name and they want justice. You never know the power of documentary, but, in an ideal world, the district attorney of Los Angeles, Jackie Lacey, would go after him criminally as she should. He should be brought to America to face a criminal trial because he ran away and has never paid his civil judgment. He’s a fugitive.

We have a new governor in California, Gavin Newsom, who’s very progressive and amazing. He’s our Trudeau. The old governor of California was Jerry Brown. There’s a photo of him with Bikram in the film and I don’t know whether they were friends or associates, but Bikram gave money to his campaign and now he’s gone. Gavin Newsom is a very progressive governor and he could lean on Jackie Lacey and tell her to open this case. I’m hoping that he will watch the movie on Netflix and do something about it. That’s the kind of leadership we need.

POV: Was an effort made to approach Bikram for the film?

EO: Yeah, very early on. I thought to myself, “Look, we will try and get him, but he will probably say no. Can we make this film without him? Yes we can.” We could because there’s so much archive. That was one of the funnest parts, but also the most challenging. One person in the film who is still very close with him suggested I contact him early on. I wrote him a letter and she passed it on to him. She spoke to him and he received it. He said he was open to it. I was dying to meet him.

POV: Really? He seems awful.

EO: When you spend a couple years of your life focused on somebody, as horrible as they are and no matter what kind of villain they are, you sort of become obsessed. You want to meet them.

POV: And I guess he declined?

EO: He said he had to pass it on to his children, who run the business now. I never heard back. I spoke to my friend a few months later and I said, “Why don’t I write another letter?” And I did and I never heard back.

At the end of the day, he’s done so much press—and so much damaging press and he’s said so many incriminating things. I don’t know what more he would have said in an interview. But we had exclusive access to his depositions. I feel like there aren’t many questions about him left when you see the film. But if you can get [the interview], you go for it as a filmmaker because you never know what might happen. It’s more out of curiosity. I would have liked to have met him and seen how he behaved.

POV: You mentioned how the film has so much archive. I really like how the film frames his character through the editing and the way everything reveals itself. What was the process of shaping the story arc?

EO: It was challenging. Kimberley Hassett, my lead editor, and Forrest Borie, another film editor, were amazing. A documentary filmmaker is nothing without her editors because it all comes together in the edit. One of the biggest challenges was the first act of the film: you have to establish Bikram’s appeal, his humor, and that world he created and all the good times. You have to show why people fell for it, why people got hooked, and why he became a guru. If you don’t show that believably, then [the survivors] will look stupid. They’re really smart people and they became part of this community. It was hard because he’s a little bit ridiculous.

POV: I can imagine the tone was a tricky balancing act.

EO: It was a challenge tonally. He’s a funny guy and you want the film to be a little bit funny, but obviously there’s a huge shift around 30 minutes into the film. It gets very dark. Once we get into the dark story, it’s quite chronological.

The other thing that maybe wasn’t as challenging, but was super fun, was debunking his whole story, his whole act. That’s my favorite part of the film. In a Trumpian world, it raises the whole concept of truthiness where people don’t tell the truth anymore. Bikram is a great example of someone who’s been doing it for a lot longer than we’re used to. He’s the pioneer of bullshit. That should’ve been the subtitle for the film. [Laughs.]

POV: But Bikram does have that profile of a charismatic leader. What research did you do into cults?

EO: I’ve seen a lot of cult films, but I went back and looked at them all. There are such similarities. It’s that very sort of predatory behavior. In this case, because it’s a physical thing, they prey on people who are injured, whether they have a weakness, whether they’re looking for something, whether they’re ex-addicts, or recovering. You see the same patterns. You see the power players honing in on the weak and making them beholden to them financially or spiritually. It’s very clear from very early on that he has a darkness and is predatorial.

POV: Both this film and Chasing Asylum, which offers covertly shot images of a migration detention centre in Australia, really have a stake in their footage, like there’s an urgency and a challenge in accessing the material. What attracts you to these stories and the hard get?

EO: And the darkness? [Laughs] It’s funny because I’m a pretty happy person.

I grew up in Melbourne, Australia. I’ve lived in America for a long time, but my parents are Jewish-Polish and were born in Poland in 1937, which is pretty much the worst timing in the history of the world. Three of my four grandparents died in the Holocaust. All of my extended family died in the Holocaust and I grew up in Australia with this fantastic life and family. I went to a nice school and had choice and privilege, but my parents had accents and came to the country with nothing. They were a little older than most of my friends’ parents.

From a very young age, I knew that bad things happen to good people. I didn’t realize any of this until much later in my life when a journalist asked me exactly that question. There’s a story I tell about when I was eight or nine years old and the genocide was happening in Cambodia. I grew up in the Jewish community in Melbourne, which is very small, but is very Eastern European survivor. There was a lot of “never again” talk in the ’70s and ’80s. It was “Never again! Never again!” I remember seeing the news on television and then seeing Cambodia on the map. It looked really close to Australia and I kind of called bullshit on everyone. That was a moment for me where I thought that we couldn’t be silenced.

With Chasing Asylum, that’s my country. I hadn’t lived there for over 10 years, but I just didn’t see anything happening. I felt like I had to infiltrate that secrecy and tell that story. I think with this story, it’s about a man who got away with it in a time where we’re trying to stop men from getting away from it. It’s recent and it’s global and it’s blatant. It’s like the R Kelly film [Surviving R. Kelly]. How is it that he was free until the documentary was made a couple of months ago? Everyone knew about him.

POV: You had a long run as a producer before Chasing Asylum, Bikram, and your other films as a director? What prompted the jump?

EO: I started working in the early ‘90s and I guess it a confidence thing with the industry. There weren’t many female directors. There really weren’t. Even now, there’s a huge push for gender parity and TIFF is amazing. There are 36% women directors here, and that sounds low, but to me, that’s so high. Ten years ago, it was probably around five percent—that’s a guess.

I didn’t have the courage and it took me 20 years of producing on a really high level and winning an Academy Award before I started to think that maybe I could do it. There have been a couple key people in my life in LA. One was an agent and one was the late filmmaker, John Singleton, who was a really close friend. He said I should be directing. That was 10 years ago. Now this is my fourth film as a director.

POV: How are you seeing the change in the industry? Is the talk just lip service?

EO: I feel like now is a great time to be a female director because people want to work with women. They take us more seriously. They listen to us more. We’re having a bigger impact. But there’s something I’ll also note, which is interesting because it’s something I didn’t even notice. My boyfriend is here with me and it’s his first film festival. He’s non-industry. We’ve been to four parties in the last couple of days. He looked around the room at each of them. He said the parties are 70-80% men. I didn’t even notice that because I’m so used to it. There is still a real disparity in the industry. Now, every time I walk into a room, I look around and I see it. But I think it’s a really good time to be a woman. I think our voices need to be heard with content we’re making. It’s definitely a battle.

POV: With the push for parity, the emphasis always seems to be the director. While the industry’s been slower to have women in the director’s seat, there seem to be more women in the producer role, but we don’t really talk about that. Do you think we need to expand the conversation beyond director credits? How do you see it having taken on both roles?

EO: That’s a tricky one. It depends on how involved your producer is in the project and what their role is. Some producers initiate the idea, shepherd it through, and create and develop the project. They have relationships with the people in your film. In the films I’ve worked on, it’s really been me doing that. But there are a lot of creative producers who are forces. I just think that, traditionally, women were more encouraged to produce. When I was getting into the film industry, people said, I’d be a great producer. Nobody ever said I’d be a great director. But that was 30 years ago. Now, if you meet someone who has a voice, is creative, and is smart, you’re saying they could be a director.

My takeaway from this film is that I’m so grateful for these women and men who put themselves out there, especially in a situation where there wasn’t a happy ending. Were you angry at the end of it?

POV: I was. It’s a bit of a journey: you find yourself intrigued, then you laugh, get pissed off, and laugh again.

EO: It’s hard just being mad the whole time. To me, Bikram wasn’t charming or funny. I think he’s a colossal dick. But people found him charming and funny, so we had to show that. I want people to laugh at him because he’s ridiculous. Towards the end of the film, Carla, the lawyer, says, “He’s a clown, but he’s a dangerous clown.” It’s actually funny, but it’s dangerous as well. But that’s the thing. He’s an idiot. He’s like Donald Trump: he’s a complete buffoon, but we’re all in this world and yet they manage to win, which is terrifying.

Bikram: Yogi, Guru, Predator premiered at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival.

It launches on Netflix Nov. 20.