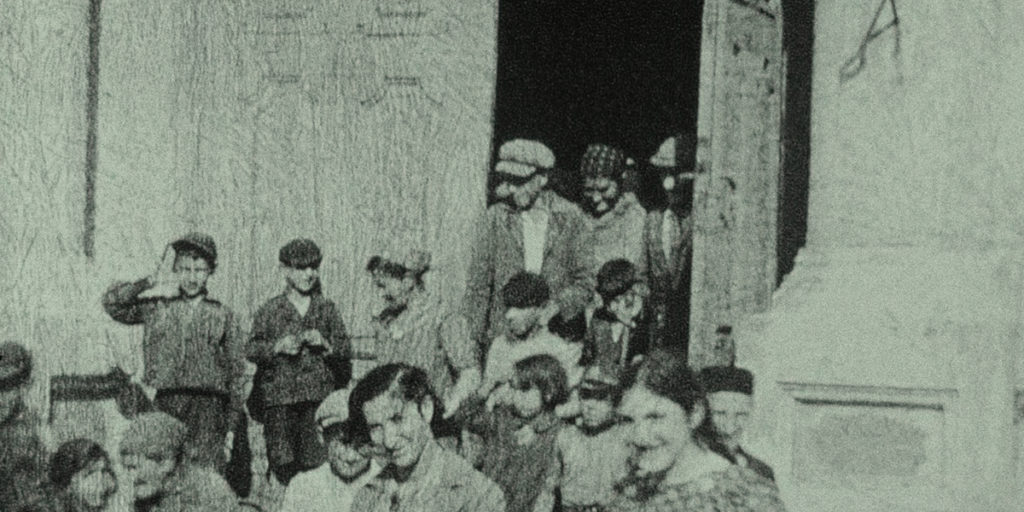

Three minutes of film footage captures a lifetime of history in Bianca Stigter’s Three Minutes – A Lengthening. The film, which screens at the Toronto International Film Festival after premieres in Venice and Telluride, intuitively interrogates the past by analysing surviving pieces of footage shot by David Kurtz in Poland in 1938. Stigter constructs the entirety of her 70-minute film from these three moments of footage. She examines the material frame by frame, observing the happy faces in a town that would soon be devastated by the horrors of the Holocaust.

Three Minutes – A Lengthening is also a deeply philosophical interrogation of film itself. Stigter plays with time and texture. Images slow or quicken to evoke the liveliness of actions on the square, or to fill in the gaps as offscreen interviewees share their stories and provide context about what happened to the people before or after David Kurtz dazzled the children on the square with his camera. The doc manipulates the frames of Kurtz’s footage in some shrewd detective work to see how elements of exposure, light, and contrast in the film stock can yield evidence that is undetectable to the naked eye.

Moreover, Three Minutes – A Lengthening is an essay about absence and the indexical power of film. Despite the erasure of entire communities during the Holocaust, Kurtz’s footage offers a record that these people existed and that they had lives and stories. The film asserts the presence of lives taken too soon and tries to understand what happened to those people and the possibilities that might have awaited them had history taken a different course.

Stigter, who makes her feature documentary debut with Three Minutes – A Lengthening after serving as an associate producer on films such as 12 Years a Slave and Widows, directed by her husband, Steve McQueen, creates thoughtful and meticulously researched film that makes one wonder about the histories tucked away in home movies or lost with the erosion of time. POV spoke with Stigter by telephone ahead of the TIFF premiere of Three Minutes – A Lengthening.

POV: Pat Mullen

BS: Bianca Stigter

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: In 2015, your short film Three Minutes Thirteen Minutes Thirty Minutes screened at IFFR. What inspired you to push from 30 minutes to double that?

BS: I presented there as a work in progress. They gave me the opportunity to start making it. I knew that there was still more to it, and then I took another five years to finish off and on. That was a good process: to get back to it, look and it, and see what works and what doesn’t work. Let it simmer a bit.

POV: What were some of the things you discovered throughout the process?

BS: I heard about this footage made by David Kurtz in 1938 with a Facebook post. His grandson, Glenn Kurtz, wrote about it in a book called Three Minutes in Poland. It was a very intriguing title, so I clicked on the post and found out that you could watch the footage on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. They digitized all the shots, not only in the town of his birth in Poland, but also in Berlin and other towns in the Netherlands and Europe.

POV: What was your reaction to that footage?

BS: I saw the footage and it made me feel that people would want to see this original footage, especially the colour parts. They are so alive—the way you can look people in the eye across years and decades. It made me feel that I could keep them in the present for longer than the short three minutes. Then I got the opportunity to make the video essay because I worked for a long time as a film critic. I read Glenn Kurtz’s book, which is marvellously detailed research. Most of the facts that you see in the film are from the book, and interviewed Kurtz about the book and that is in my film. Sometimes he reads passages from his book.

POV: The process of this film resembles a mix of research and detective work. I love the sequence where the film investigates the letters of the grocery store sign. Was that something that came during your work with the film, or is that in the book?

BS: This part is one of the things that came really came through during filming. In the book, it says—and we see this in the film—that they tried to make the letters legible. But it just doesn’t happen because they’re too faded. No matter how much you blow them up, you reach the edge of what you can know from a film image because some things are just too vague. Whatever you do with them, they keep on being vague.

Then I went to Nasielsk because I wanted to see it for myself and go to record sound. We hired a Polish researcher and she had Polish directories and phone books where she could look up names. For me, it was also interesting because the survivor who’s in the film remembers a lot. He has a very good memory, but as we all know, sometimes your memory needs to be triggered by something. At first, when he saw the movie, he couldn’t give the grocery a name. But when the researcher said, “Could it be this name?” he said, “Yes, of course! That was the name of the people who owned the grocery store across from my house in the square in Nasielsk.”

POV: What were some other instances of detective work in the film?

BS: There are certain moments where you could almost go into the absurd if you wanted to know everything. But you can’t know the most important thing: who are these people? We give names, but it’s impossible to know everything. For instance, we can see a flower on a windowsill and the red is very visible, so we sent pictures of it to botanists. They said that the images were so faded that it was impossible to make an identification based on these images. Another instance, we wanted to know what someone is saying when they are clearly speaking, so we got a lip reader who could speak Yiddish and Polish. He had a look at the film, but also said, “No, we can’t say with any certainty what is being said.” It’s very enticing to be so near yet so far, but there are words that everyone uses in that kind of situation [to create a scene of people at a restaurant], like “food,” or “fork,” or “hello.” I had people say the words, and words like “Nasielsk,” “train,” or “synagogue” that must have been spoken when these people gathered at a restaurant.

POV: But did you find that the inability to define things actually opened the film?

BS: You always do you try, but the fact that you can’t find a name also, of course, gives it something melancholy. You then have something that is so visceral and so physical that you can really see it. But there’s a limit on what you can find through the images alone. In the book, Glenn Kurtz, uses sources other than the film material—records, photographs, and the recollections of people who survived that don’t appear in this movie because they passed on. There’s much more research that could not be incorporated in this film.

POV: The first thing I did after watching this film was to go on Google Maps, look up Nasielsk on street view, and browse through the streets. It looks different: they have a Tesco now! So I was wondering how technology has changed your work as a researcher?

BS: Without Facebook, I probably would not even have found the footage from 1938 and made this film. Yes, of course, it’s changed things. Film and photography are themselves major changes because technology gives you a whole other relationship with the past because you can see those people on a given day. Then, of course, you get all the changes through the internet—you can access information so easily, but at the same time, it makes it more fleeting. There’s such a barrage of images that it’s hard to concentrate on one image or a few images. With this film, we tried to slow down the process of watching.

POV: You’re working with a limited amount of material in this project, but it also seems like a wealth of material in terms of what you can choose to explore. How did you select which images could fill in the gaps, like in the sequence where the film zooms in on an obscure image as we hear about the villagers herded off to the church?

BS: That’s what I wanted to show: the gap, the absence. These images are all we have. The images in the movie are from 1938, but you also want to tell what’s happened to these people, like a year later when Poland was invaded by Germany. In December 1939, deportation started and it started on that square. We have one image, really, of the cobblestones on the square. Although it is mentioned in the text [by Kurtz] that the German soldiers were taking photographs, those pictures, as far as I know, have not survived or have not come to light. Maybe they are still lying somewhere in the attic of a German soldier, but this is all we have.

POV: How do you balance your role as researcher with your work of a producer? How are they compatible?

BS: While I was making this movie, I was working on another project because my work in daily life is as a writer and as a journalist. It’s a kind of guidebook—neighborhood by neighborhood, street the street—about what happened in Amsterdam doing the Second World War. My historical imagination is what triggers me: what was here before and how can we present that in new ways? We could see how people were in hiding, like in Anne Frank’s house, within different neighborhoods or even a few houses. That’s a different way to present history. The book came out at the end 2019, so after that, I had time to finish Three Minutes.

POV: I assume the book you’re talking about is The Occupied City? I understand there’s a film coming out based on that, so how does it feel to have your work adapted into a film?

BS: Wonderful! It’s interesting to see because film and text work in very different ways. We were filming at the house of Anne Frank not so long ago without any visitors there—just the film crew and the director is Steve, so it’s very interesting to watch and see how they film it. Then it becomes even more than when you read the book because you see the old and the new in one image. It’s a new way to present history.

Three Minutes – A Lengthening screens at the 2021 Toronto International Film Festival.