It’s a sight that is shocking in its ferocity and violence. Federal Canadian ships are seen deliberately ramming into small boats driven by Mi’kmaq fishers. The ships, operating as part of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), slam the hapless vessels, pitching all the Mi’kmaq men onboard into the water. One of the fishers struggles to reach the surface and needs help but the DFO officers do nothing; a Mi’kmaq dives further into the Miramichi River and saves him. Onshore, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) do nothing to stop the terrifying event they’re seeing.

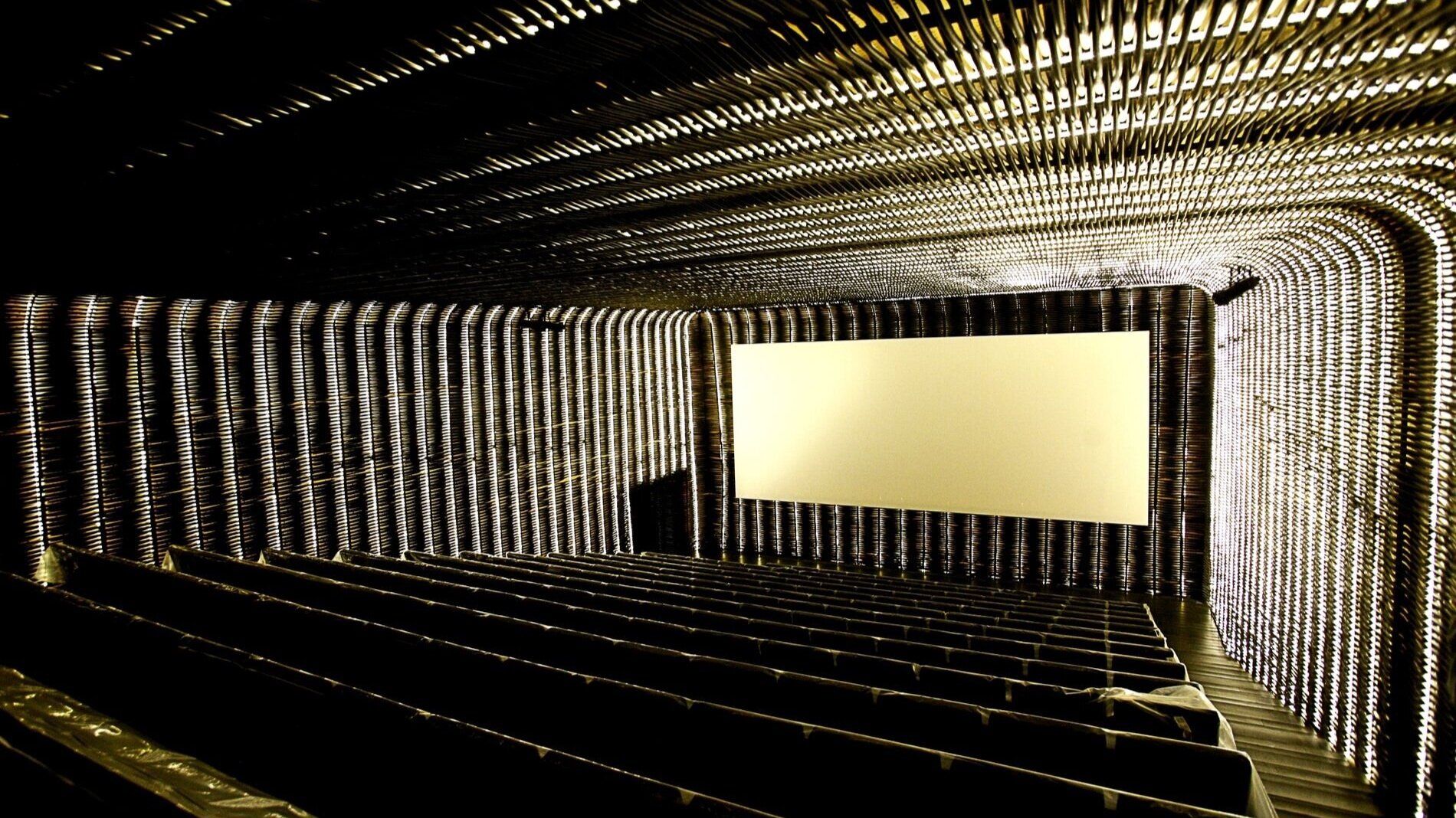

Viewing it today, the footage is as disturbing as it was nearly 20 years ago, when it was first screened in Canadian and international festivals. The film in which it appears bears a title that resonates with any group that has dared to defy the Canadian establishment by its very presence: Is the Crown at War with Us? (Alanis Obomsawin, 2002). With the RCMP arresting Wet’suwet’en land defenders to force through a pipeline in February, Black Lives Matter protests taking place across the country over the summer, and a new wave of white violence against Mi’kmaq fishers this fall, many have been prompted to join in asking this question.

The Mountie State

Canada is, of course, a classic settler country, which inherited the attitudes of the imperial power, the British Empire, that allowed it to become a confederation. This has meant that, while proclaiming an egalitarian mandate, Canada, from John A. Macdonald on, set out to marginalize Quebec, suppress the French presence out west, push Indigenous people into reserves, pursue racist immigration policies, and come down with a heavy hand on LGBTQ communities. Anybody not conforming to the Canadian ideal of being wealthy, white, English, and male could be a target.

Backing up Canada’s true policies were the Army and, after it was created in 1873, the North West Mounted Police. It is surely significant that the Mountie—depicted as a square-jawed athletic outdoorsman wearing red serge and a Stetson, always on the ready for a fair fight—has become one of Canada’s most internationally recognized symbols. Enamoured of the Mounties and their international appeal, Canada and Disney once pursued a five-year-deal to better market the stalwart figure around the world. Yet belying this benign image is the reality of the Mounties’ historical mandate to suppress and, if necessary, kill the people who oppose it.

Yet overt violence has been the exception, not the rule. State violence in Canada has tended to be subtle, enacted in sins of omission as often as commission, and always just enough to suppress radicalism without compromising the country’s essentially benevolent image. It’s been successful, too. Though some flashpoints have received the documentary treatment, many haven’t. Almost all of those that have, moreover, come courtesy of members of the affected communities. If Canadians are to overcome our historical amnesia and recognize this country for what it is, we will need to pay attention to both the films that have been made and those that haven’t.

Obomsawin

Nowhere has the true mandate of the Canadian police been clearer than in its treatment of Indigenous peoples, and nobody has chronicled that relationship more vividly than Alanis Obomsawin.

The background of Is the Crown at War with Us? is a protracted legal battle. In 1993, Donald Marshall, Jr. of Cape Breton’s Membertou First Nation, was charged by the DFO with illegally catching and selling eels—for a price of less than $800. Marshall refused to pay the fine and took the matter to the Supreme Court, which ruled in 1999 that Indigenous people in the Atlantic region had the right to make a “moderate living” from the waters, which they have fished for centuries. This ruling allows Mi’kmaq to fish in small amounts outside of the regular seasons and pay a lower figure for their licenses.

Obomsawin was prescient. 20 years later, the very same issues are back in the news. This time, it’s the Sipekne’katik, the Nova Scotia cousins of the New Brunswick Mi’kmaq profiled in Obomsawin’s film, defending their right to harvest lobsters. Over the past few weeks, fishing traps have been destroyed and fishing boats have been threatened. In early October, Randy Sack, who is Donald Marshall’s eldest son and the first recipient of an Indigenous fishing license in Nova Scotia, was threatened by a hostile group of white Canadians, who threw rocks at him and a friend in the local Indigenous fish processing plant. Escorted out by the RCMP, they watched as their catch was thrown into the water. Three days later, the plant burned down under suspicious circumstances. In an echo of the events in Obomsawin’s film, the RCMP failed to defend the Mi’kmaq fishers and their property.

It’s in Obomsawin’s masterpiece, Kanehsatake: 270 years of Resistance (1993), that the battle lines between the RCMP and Indigenous people are most clearly drawn. The subject was the 1990 Oka Crisis, in which Quebecois authorities in Oka decided to build a golf course over sacred burial grounds of the Mohawk. Obomsawin spent 78 days behind the lines with the Mohawks (part of the Haudenosaunee Nation, as are their allies, the Akwesasne) in near battle conditions. Her footage is raw and explicit showing the hostility by the Mounties, the Canadian military, and the Sûreté du Québec towards the Mohawks, the Indigenous defenders of the disputed land. Obomsawin’s film shows how organized and peaceable the Mohawk were during the dispute, in contrast to the bellicose representatives of the Canadian security state and sundry white rock-throwing hooligans.

Although Kanehsatake won awards and is one of the best feature documentaries made in Canada, the CBC refused to broadcast it at first, presumably because its pro-Indigenous point-of-view violated the national TV service’s ostensible “objectivity” requirement. It was only under public pressure that the CBC yielded and showed the film. In the book The Cinema of Canada, film critic Brian McIlroy measures the film’s importance: “It is clear that without Obomsawin’s 1993 film, the history of Oka circa 1990 would be dominated by [Prime Minister Brian] Mulroney’s assertion, reproduced in the documentary, that the armed Mohawks were criminals and illegally wielding weapons.” Not only the RCMP but the CBC would have been complicit in that lie.

October Crisis and Brault

While the vicious relationship between the Crown and Indigenous communities is on-going, the conflict between Quebec and the rest of Canada was largely played out in the ’60s, after 90 years of de facto colonization by the English of the French. Throughout that decade, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), the most militant group advocating for Quebec’s independence from Canada, undertook a series of bombing attacks. In October 1970, the FLQ moved on to more insurrectionary tactics, kidnapping the British trade commissioner James Cross and Quebec’s Deputy Premier Pierre Laporte. In response, at the invitation of the Quebec government, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act during peacetime for the first and only time. The next day, Laporte was executed by the FLQ. Over the next few months, hundreds of people—activists, unionists, intellectuals—were arrested and held without charge. Due to this brutal response, Parti Québécois leader René Lévesque spoke for many when he said, “Until we receive proof to the contrary, we will believe that such a minute, numerically unimportant fraction is involved, that rushing into the enactment of the War Measures Act was a panicky and altogether excessive reaction.”

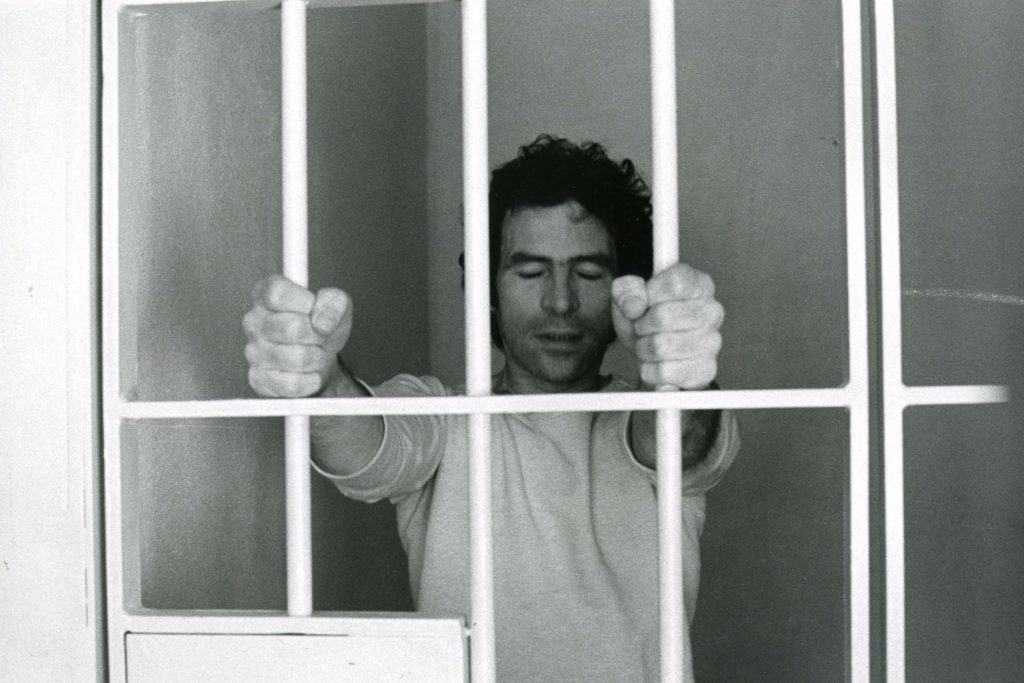

It was in response to these events that Michel Brault created what might be the finest film ever made in Quebec or, indeed, in Canada: Les ordres (1974). A docu-drama inspired by people who were wrongly incarcerated by the War Measures Act and shot verité-style by Brault, a masterful cinematographer, it feels absolutely realistic. Brault’s directorial coup was that, while keeping the stories real, he had actors play the parts of these victims of the Act, transforming their accounts into tales of the Quebecois, not simply about themselves. The actors introduce themselves in the first quarter of the film, exposing their dramatic artifices in a Brechtian manner. The five are playing a factory worker and former union rep; his wife; a feminist social worker; an unemployed man who cares for his two kids; and a physician who runs a clinic in a poor neighbourhood.

Hannah Arendt’s description of fascism as “the banality of evil” fits perfectly in this quasi-documentary as each Quebecois is rounded up by the police, dragged unceremoniously into prison, and made to suffer the humiliation of having their rights laughed at. Beards are shaven, dresses discarded, and every protest monitored. The worst to suffer is the unemployed man, Richard Lavoie (played by Claude Gauthier), who angers the prison guards by his careless, slightly insouciant manner. The guards conspire to frighten him into believing that he’ll be executed; when they stage the shooting, he fearfully passes out. On his release, Lavoie has to seek psychiatric treatment to survive.

In Brault’s film, the point is made that “nothing happened.” Except for Lavoie, none was beaten. Yet by refusing to tell them their legal charges, because there were none, and limiting what they could do each day—a prescribed time to walk, eat, sleep, and talk to each other—they reduced the prisoners into victims. That’s the Canadian system: few deaths or spectacular beatings are meted out against our rebels. Instead, they are so humbled that asserting themselves no longer feels like an option.

The Bathhouse Raids

In a 2016 article in The Walrus, Matthew Hays took issue with the way in which the 1981 Toronto bathhouse raids, in which police forced their way into a number of bathhouses and rounded up hundreds of gay men, were commemorated as the turning point in LGBTQ history in Canada. In fact, he points out, quite the same thing had happened a few years earlier in Montreal. “On October 22, 1977,” he writes, “police raided two downtown Montreal gay establishments, Truxx Bar and Le Mystique, arresting 146, in what would be the largest mass arrest since Trudeau had declared the ‘War Measures Act’ during the October crisis.” Mass protests followed, just as they did in Toronto a few years later; but in Quebec, the protests were successful. “On December 15 of that year,” Hays writes, “Quebec’s National Assembly would amend the Quebec Human Rights Charter to include sexual orientation as a prohibited form of discrimination. That made Quebec the first province in Canada, and the largest jurisdiction in North America, to ever provide such protection under the law.”

As it happens, filmmaker Harry Sutherland made films about both events. Track Two, his film about the Toronto raids, co-directed by Gordon Keith and Jack Lemmon, is particularly strong, a time capsule of the early 1980s in Toronto all the more poignant for its amateurism. Originally supposed to be a film about George Hislop’s campaign to be Toronto’s first out alderman, the raids widened the scope of the film to take in Toronto’s queer community generally and its relationship to the police in particular. In the opening moments of the film, Hislop explains that the police seem to view the entire LGBTQ community as prostitutes; after the raids, a victim says he understands how his parents felt at Auschwitz. In the face of opposition from the Toronto Police Association, both Hislop and progressive mayor John Sewell were defeated at the polls. Yet by the end of the film it’s clear that the raids were galvanizing for the community, leading to new forms of political organizing.

It wasn’t until 2016 that the police officially apologized for the raids, and even with that, relations remain tense. The police came in for particular criticism in the midst of the Bruce McArthur investigations for ignoring the community’s suspicions about the disappearances. For that and other reasons, Pride Toronto has banned uniformed police from the annual parade since 2017. Though controversial—Toronto, like Canada as a whole, is more conservative than it pretends to be—this has opened up a space to talk about police in Canada and rewrite its history.

The films that haven’t been made

While the bathhouse raids and the October and Oka Crises have been written into history, there are equally important flashpoints in Canada’s history of policing that have not received the documentary treatment. Two in particular stand out. The first is the case of Louis Riel. Of all Canada’s rebels, Riel came closest to transforming Canada, leading rebellions in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Both times, he was betrayed. The army was on hand to do Macdonald’s bidding in Manitoba, and the Mounties the second time in Saskatchewan. Riel was hanged for his efforts to integrate the Indigenous and French into Canada’s DNA. Perhaps because his Métis roots haven’t driven either Indigenous or Quebecois filmmakers to advocate for him, there is no artistic documentary or narrative film on Riel, and the high-profile musical and literary treatments of his story are, for their merits, problematic. The 1967 opera by composer Harry Somers and librettist Mavor Moore is worth seeing, though it is noteworthy that it was only with director Peter Hinton’s 2017 staging that Indigenous people were brought in to play Indigenous roles. Chester Brown’s graphic novel Louis Riel, for its part, is brilliantly researched and did much to bring Riel’s story to prominence but drew criticism for its portrayal of Riel as a naïve, religious progressive thinker.

The second major lacuna in this story is the Winnipeg General Strike. From May 15 to June 25, 1919, over 30,000 workers left their jobs to protest wages, poor working conditions and the lack of social services throughout the city. During that time, something resembling a worker’s paradise took over downtown Winnipeg, with food distribution, craft-making, and even bicycle lessons being led by the workers’ committees. The sinister Citizens’ Committee of 1000 propelled a confrontation between the strikers and Winnipeg’s city officials, who were in their pockets. A force made up of Mounties and “special constables” opposed to labour ruthlessly led troops through downtown Winnipeg on Bloody Saturday, June 21, killing two strikers and injuring 27. David Lester’s graphic novel 1919 is a good introduction to the Strike but the definitive adaptation has yet to be made.

Of course, the major flashpoint for policing in 2020 is Black Lives Matter. Robin Maynard’s book Policing Black Lives lays out the case of systemic racism towards Blacks. It includes this bold but accurate quote from writer and filmmaker Dionne Brand: “The historical relationship between Black peoples in Canada and ‘mainstream’ society has been one of subordination.” Charles Officer’s The Skin We’re In (2017), a sympathetic portrait of writer Desmond Cole, is the closest Canada has gotten thus far to a BLM documentary. Cole, of course, made waves when he wrote material like this: “I have been stopped, if not always carded, at least 50 times by the police in Toronto, Kingston, and across southern Ontario … Because of that unwanted scrutiny, that discriminatory surveillance, I’m a prisoner in my own city.” In articulating so clearly the stakes—subordination, surveillance—these writers and filmmakers have sharpened the conversation about police in unprecedented ways.

Marc Serpa Francoeur and Robinder Uppal’s Above the Law (2020) [released as well in feature length with the title No Visible Trauma] picks up these themes in the present. The film tells several stories, including one on Godfred Addai-Nyamekye, a Ghanaian-born man who was picked up by Calgary police in December 2013, brought to the edge of town in an eerie echo of the infamous freezing deaths of Indigenous people at the hands of Saskatoon police. When he called for help, he was beaten by Constable Trevor Lindsay and charged, astonishingly enough, for having attacked the police officer. Lindsay remained on the force, going on to assault others. The truth only came out because of a lucky accident: footage of what really happened was shot by a police helicopter. In another story, Above the Law exposes what has become all too familiar, the deadly wellness check: for police, mental distress is just more deviant behavior that needs to be brought under control, by whatever means necessary.

These cases and this discourse don’t just reflect upon the systemic problems in Canadian policing, they also point the way forward. If Canada is to live up to its egalitarian promise, the mandate of the police and the security state must be radically rethought and restructured. In bearing witness and deepening understanding, documentaries can and should help in this necessary process.