Film is always late. The sheer cost, technical expertise and logistical coordination needed to make a film, at least along the lines of the North American industrial model, are prohibitive to the kind of timely production that would keep abreast of events as they happen.

I wonder if this state of affairs has engendered a certain conservatism among filmmakers. Take the so-called New Hollywood generation, the closest that the USA got to a New Wave. It’s only the rare exception that betrays any awareness of the social, political and economic revolutions of the ’60s and ’70s—and even then, the effort almost always comes off square. These filmmakers didn’t aim to be timely or revolutionary the way that the musicians, fashion designers and artists of the time did, or the way that New Wave filmmakers in Europe, Asia, Latin America and Quebec did. Coppola, Scorsese, Bogdanovich and the others wanted to make classics, canonized alongside the best of Ford and Welles et al. They looked backwards for inspiration.

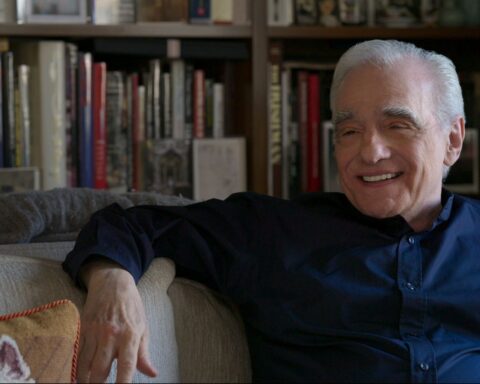

Bob Dylan and Martin Scorsese are nearly the same age, but Scorsese is culturally a decade older—as if he missed the sixties and is trying to catch up, and the effort is somewhat transparent. (That’s no knock—many great directors are out of synch and the tension is energizing.)

— Richard Brody (@tnyfrontrow) June 11, 2019

Martin Scorsese is possibly the strangest case of this temperament. As the New Yorker’s film critic Richard Brody pointed out on Twitter, Scorsese is almost exactly the same age as Bob Dylan (Dylan was born in 1940, Scorsese in ’42) but seems a generation older. In spite of being a born and bred New Yorker who attended NYU in downtown Manhattan throughout the mid ’60s, Scorsese seems to have missed the decade completely. His concerns over the course of the ensuing decades have remained steadfastly traditional: redemption, Italian-American identity, masculinity. Yet he seems to have belatedly realized that he was missing something and has spent much energy living the ’60s vicariously. He was the assistant editor for Woodstock (by his own admission, he spent the entire festival behind a camera in a cramped booth fixed on the stage, almost never saw the audience and was allergic to everything on Yasgur’s farm); directed The Last Waltz — itself a belated eulogy for the ’60s — as well as Shine a Light, about the Rolling Stones, and No Direction Home, about Bob Dylan; and has thrown “Gimme Shelter” into seemingly every movie he’s made in the last thirty years.

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story By Martin Scorsese, his new documentary about Bob Dylan’s 1975–76 tour of the same name, throws this Boomer psychology into relief. The film marvels in Dylan’s musical prowess across an abundance of live footage, in the audacity of the tour’s small-town, small-venue, “real America” setting, in the cast of characters on the scene or in the tour: Patti Smith, Allen Ginsberg, Joni Mitchell, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, etc. Much of the film consists of concert footage from the tour, with contemporary interviews—some real, some fictional—punctuating the musical scenes. All of it is very much in awe of “those heady days.”

A certain genre of critical writing has, perhaps predictably, emerged in response to the film: critics of a certain vintage have taken to recounting their halcyon memories of the Revue in their reviews of Scorsese’s Revue. To a man—and, indeed, they are all men, and all white, for that matter—they recall the Revue as a sort of watershed: not just a great show, but the great show of their youth, the show that changed everything. Such is the gravity of the tour and of Scorsese’s film that the New Yorker ran two separate articles about it, the one a mixed review by Richard Brody, the other a rosy reminiscence by the editor David Remnick. Here’s Remnick:

“If you’re lucky, at some point in your life you get to witness some flashing fraction of what music has to offer. Accidents of fate and the moment. I was too young to see Dylan’s early acoustic performances, his electric breakthrough at Newport, or the 1966 British tour with the Band. And there’s no time machine, only tape, to get me to the Regal for B. B. King, in 1964, to the Apollo for James Brown, in 1962, much less to one of Billie Holiday’s final concerts at Carnegie Hall, in 1956. Your luck and your time come when they come. My lucky moment was the Rolling Thunder Revue at a college gym forty-five years ago in New England; for those who missed it, your time has come.”

Before I come to the point, some context. Let us recall that we are talking here about 1975 or maybe 1976. What was going on in music in those days? Rock had gotten bloated and had seen its cultural relevance fade; soul had morphed into funk and disco; punk was still in its infancy. For kids not plugged into the increasingly diverse and vital underground but hungry for music that spoke to them, it was slim pickings.

Of course, those who were plugged in felt differently. Simon Reynolds’ Retromania and David Stubbs’ Mars By 1980 both hone in on Donna Summer’s Giorgio Moroder-produced Hi-NRG classic “I Feel Love” as their watershed moment of that period. It hit the airwaves in 1977 and, to these music writers—both white male Brits of the same late-Boom generation as the Revue critics—its hyperkinetic beat, electronic instrumentation and extended form seemed the very sound of the future. (Which it turned out to be.)

Why then did all these young people around North America seem to have had that same epiphany at the behest of a bunch of overripe ’60s folkies play-acting half-understood fantasies of pilgrims and Indians and minstrels and medicine shows? And what is it about Scorsese’s doc that resonates all these years later?

The byword is authenticity. The story is that the Rolling Thunder Revue saw Dylan the folk hero abandoning the corporate stadiumrock excesses of his 1974 comeback tour with the Band for a return to his roots, to America’s roots, to authenticity as such. The irony is that the tour was pure pastiche: the music of an earlier moment, the ’60s, performed in mimicry of a grab bag of yet earlier moments (the Old West, the antebellum South, 17th-century New England…), all of it, as Dylan admits in the film, ultimately being about nothing at all.

The distance between the advertised authenticity and the reality of pastiche is rendered incoherently in Scorsese’s film. It points out Dylan’s self-mythologizing, the strangeness of the white makeup he wore and the half-remembered and even latterly constructed nature of this memorial archive of the actual tour. That, I guess, is the point of the Méliès clip that opens the film and of the unannounced mockumentary elements interspersed throughout it. It’s strange for Scorsese to try being sly after a career built on bombast, and he doesn’t really pull it off; he seems to be playing into the Dylan myth instead of revealing it.

Which brings me back to Remnick’s remarkable last line: “My lucky moment was the Rolling Thunder Revue at a college gym forty-five years ago in New England; for those who missed it, your time has come.”

He has missed the point so spectacularly he’s given up the game. It’s telling that Remnick’s praise can only arrive in vague platitudes about the power of music, saying nothing substantial about what that power might actually be. That he concludes by inviting contemporary audiences to indulge in Dylan’s pastiche at yet another spatiotemporal remove, as though it will be the authentic experience for us that it never really was for the Revue’s actual audience—and, crucially, as though nothing happening today could possibly compare—says everything about the hollowness of the tour and the film.

There’s no accounting for taste, of course. If you love Dylan, that’s your prerogative, and in that case, you’ll probably love Scorsese’s film. (A scene with Joni Mitchell playing “Coyote” at Gordon Lightfoot’s house in Toronto is genuinely great.) But it speaks to a point Reynolds makes in Retromania about the mutation of rock’n’roll: “Once, rock’n’roll was a commentary on adolescent experience; over time, rock itself became that experience, overlapping with it and at times substituting for it entirely.” At its advent in the mid ’50s and up until the mid ’60s, rock was bound up in the invention and experience of adolescence as such—sex, drugs, cars, freedom, the whole American Graffiti bit. By 1975, it was hollow, decadent, a spectacle that vaguely suggested that vital, oppositional lifestyle while not being organically linked to it anymore—if it even existed at all in that historical moment of cultural decadence, economic decay and ideological waywardness. Looking at the live footage of the Revue in Scorsese’s film, it feels (and, uh, sounds) more like community theatre than rock’n’roll. Yet for some, that simulacrum of rock’n’roll’s original vitality is enough.

As for the film’s resonance all these years after the tour, it speaks to nothing so much as the force of the archive as such. At the beginning of his book Archive Fever — otherwise a boring monograph about Freud — Derrida points out that the etymology of archive is the same as that of the arch in words like monarchy: it refers to both origin and authority. There’s something about seeing the kind of footage in Rolling Thunder Revue — or, really, any film about the period from about 1960 to 1975—that seems to give certain critics “archive fever,” whereby the sheer repetition of a past experience is a joy unto itself. To me, that bespeaks a clear anxiety about the direction of history after that insistently repeated golden age. For these critics, in the throes of archive fever, watching films like Rolling Thunder Revue is like looking back at a lost utopia, and the thing to do is just bask in it. The rest of us are left wondering what’s the big deal.

Let’s compare the phenomenon of Revue’s elated reception to the more muted, if respectful, response to what I consider to be a better film in much the same genre: Amazing Grace, the legendary “lost” film of Aretha Franklin’s 1972 gospel concerts that gave rise to the bestselling album of the same name. (As of this writing [August 2019], it has under 1000 ratings on IMDb, while Rolling Thunder Revue has over 2500.) For a variety of good and bad and inscrutable reasons it had never seen the light of day until after Franklin’s death. Technical problems in its original production by director Sydney Pollack led to Franklin burying it, though why it took until now to restore it, despite periodic efforts by eventual producer Alan Elliott and others, remains a mystery. It finally screened at festivals in late 2018 and saw worldwide theatrical release earlier this year.

There are no tricks here: the film is a straight-ahead document of what happened at those concerts. At moments, the technical lapses involved in the original production are evident, but by and large it’s absorbing. And, for me, almost overwhelming. I know the album that resulted from these concerts quite well, but even that couldn’t prepare me for the immersive immediacy of the footage itself—of the sweat and tears running down Franklin’s face, of the members of the choir jumping out of their seats and holding their heads at the virtuosic, melismatic climax of “Amazing Grace,” of Franklin and Rev. James Cleveland holding each other’s hands for dear life behind their backs in the throes of religious ecstasy, of Cleveland sermonizing that, twenty years earlier, when Franklin was first performing, it didn’t seem like the Lord had much good in store for Black folks in America.

I mean, it’s something to behold. For me, anyway.

Maybe it’s the absence of Scorsese’s name in the credits that has held it back. Maybe it’s that it wasn’t released on Netflix. But part of me thinks that the kind of people who are film critics in 2019 just don’t care about Aretha Franklin the way they care about Bob Dylan. After all, Aretha was a “diva”—whatever that is—while Dylan is a “genius”—whatever that is. And she’s just singing old gospel songs everyone knows, not gnomic folk-rock epics. Let’s just say that Revue often felt ridiculous to me in a way that Amazing Grace, in its beauty and sincerity, didn’t, and Amazing Grace felt powerful in a way that Revue, in its irony, couldn’t dream of.

Am I falling into the same trap as the Boomer critics, but laid by a different film? Certainly I share the sense of the ’60s and ’70s— decades before I was born—as a sort of socio-politico-cultural highwater mark. I think most people do. Yet I feel there’s a distinction to be made between Scorsese’s “archive fever” and the way in which I experience Amazing Grace. For me, Amazing Grace is almost overwhelming in its immediacy and almost immeasurable distance: a pure experience of total difference.

Allow me another theoretical digression to make sense of this. In the Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin introduces the concept of the dialectical image. Though its exact meaning remains elusive, the thrust of it is an understanding of history as a dialectic between a discrete moment in the past and a present trying to understand and experience it. The past remains irretrievable but via the archive, we experience it not as “history,”—one event in a series of events, laden down with a certain authority, which we search through anxiously, almost traumatically, for answers—but as a “now,” a moment phenomenologically equivalent to the present, both inside and outside history, with the two moments colliding in a productive dialectic.

This is how I experience Amazing Grace. Eschewing the augmentation and trickery that Scorsese brings to the Revue, all of which inflates the Revue into a grandiosity that the material, to my mind, can’t really support, Amazing Grace remains discrete in its historical moment, a simple document that yet, by virtue of its simplicity, channels all its ideas and emotions organically. As such a document, it is both wildly effective as sheer pathos and also thought-provoking in a sort of comparative dialogue with a present, 2019, that is both very like and very unlike the 1972 we see on the screen.

There is a third film in this vein to have hit the cinemas last year: Apollo 11, quite masterfully assembled by Todd Douglas Miller. (Let’s not even get into Echo in the Canyon, Marianne and Leonard, Gordon Lightfoot: If You Could Read My Mind, and any other of the myriad boomer-nostalgia docs-by-numbers that have come out recently. Though their entropic proliferation does speak to the apparently eternal pull that generation has on the collective consciousness, they have rather less to say about that pull than the more stringent archival films do.) Like Amazing Grace, in broad strokes, Apollo 11 is a reconstruction: using only audio and video footage from the 1969 moon landing, it creates an immersive narrative of those epochal events as they transpired. Such technical details of the landing as there are in the film are shown on ancient computer monitors or incomprehensibly muttered between the three astronauts and the ground crew; in their place is the carefully built illusion of being there, of seeing history as it is made.

Most current historiography understands the space landing as a key event of the Cold War, and American jingoism is certainly present in the film. Yet overwriting that is an insistence on the event’s universality; one senses they would have liked to have called it For All Mankind if that title weren’t already taken. Though these ideas—American exceptionalism on the one hand; universalism on the other—seem contradictory, they aren’t, exactly: what the film (maybe inadvertently) clarifies is that American exceptionalism is an assertion of American universality. For Americans, what happens in the U.S. is of world-historical importance, while events elsewhere pertain only to their specific contexts. (One might say the same of the USSR at that time. It was those dueling hegemonic universalisms that gave the Cold War its imperialist shape.) Apollo 11’s double drama—one small step for [a] man, one large leap for mankind—is so skilfully constructed that I found myself buying it almost entirely. Here, after all, is a collective accomplishment leaps and bounds beyond anything dreamed of today.

Yet that chimerical universalism-exceptionalism is worth unpacking because of everything it gave rise to in the coming years. The long story of the space race after the success of Apollo 11 is, of course, pathetic. Reynolds, in Retromania, reports that “[NASA]’s annual budget sank from $5 billion in the mid-sixties to $3 billion in the mid-seventies… By April 1970, TV coverage of the Apollo 13 mission was being cancelled in favour of The Doris Day Show.” The long story of the ’60s musical revolutions that Bob Dylan was a part of is also, in large part, dismal: there’s a direct line from Woodstock to modern corporate music festivals like Coachella and from Dylan’s milieu to the commodification and ossification of oppositional lifestyles. The Civil Rights movement—the subtext of Amazing Grace’s most powerful moments—is similarly vexed: as Black Lives Matter and writers like Keeanga Yahmatta-Taylor have so eloquently shown in recent years, the long story there is as much about lingering racism and massive structural inequalities as it is about legal and political victories.

To an extent, that metanarrative is also well-known, and films about the various failures of the ’60s and the disintegration of its hopes date at least as far back as Chris Marker’s Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977), and probably further than that. And yet the knowledge of what happened next has never been allowed to tamper with the narratives about what happened. To me, this failure to revise that fundamental misunderstanding of the longue durée bespeaks an anxiety. If the golden age has to remain a golden age, it’s because an entire generation’s self-understanding, if not that of large segments liberal Western society in general, rests on the illusion of the ’60s as the fount from which all good things flow. (Even as original and incisive a thinker as Mark Fisher could only found his inklings of a better future on dreams of the ’60s, under the heading of “acid communism.”)

This misunderstanding is only a problem insofar as it blinds us to the progress of history and the changing meaning of culture since the ’60s. Rolling Thunder Revue rankles because it ultimately amounts to an uncritical celebration of a grotesquely extended ’60s, which literally persists up through the present. Scorsese’s film ends with a catalogue of all of Dylan’s tour dates after 1976, a catalogue which is necessarily incomplete because he is still, now, touring. It makes an honest reckoning of the actual significance of Dylan’s landmark tour impossible. If Amazing Grace and Apollo 11 are more satisfying, it’s because they feel better situated inside and outside history. If they don’t rectify historical misunderstandings, exactly, they certainly don’t obfuscate them further, as Revue does, and the way they successfully immerse us in the emotions of history without attempting to bridge the unbridgeable temporal divide between past and present has, I think, a clarifying effect.

“As much as and more than a thing of the past, before such a thing, the archive should call into question the coming of the future,” Derrida writes in Archive Fever. The archive, that is to say, is a relationship between past and present, a construction of the past that says as much about the present as it does about the past, which is in fact predicated on an anxiety about the future—both the actual future and the future of that archived past. When, in Rolling Thunder Revue, Dylan laments that “today’s poets don’t reach into the public consciousness,” he speaks to precisely that anxiety. In the first place, he’s talking about how poets of his generation don’t measure up to Allen Ginsberg, but one also senses that he’s taking a shot at musicians of subsequent generations who don’t measure up to himself: the future can only be figured as worse than the past. It’s that declinist narrative, which frames the whole film, that I take issue with. It forecloses the future when we desperately need to open it up.