The COVID-19 pandemic has been called “the great equalizer,” but that could not be further from the truth. Coming in like a wrecking ball that unexpectedly broke off its chain, the pandemic has smashed through seemingly unbreakable societal walls. Not only did it expose the fragile nature of global economic models but it also shone a piercing light on just how deep the roots of racial injustice are planted in every facet of society.

The tragic deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor have caused many industries and individuals to take an uncomfortable look at systemic racism and, in some cases, their unknowing complicity in it. While much of the broader discourse has focused on police brutality, one cannot cure a symptom without acknowledging the cause. To truly grasp the depths of racial inequality and the activism it often sparks, it is important to understand the struggles that come with everyday Black life. As author Chelsea Kwakye states in the introduction to her book Taking Up Space, being “a minority in a predominantly white space, to take up space is itself an act of resistance.”

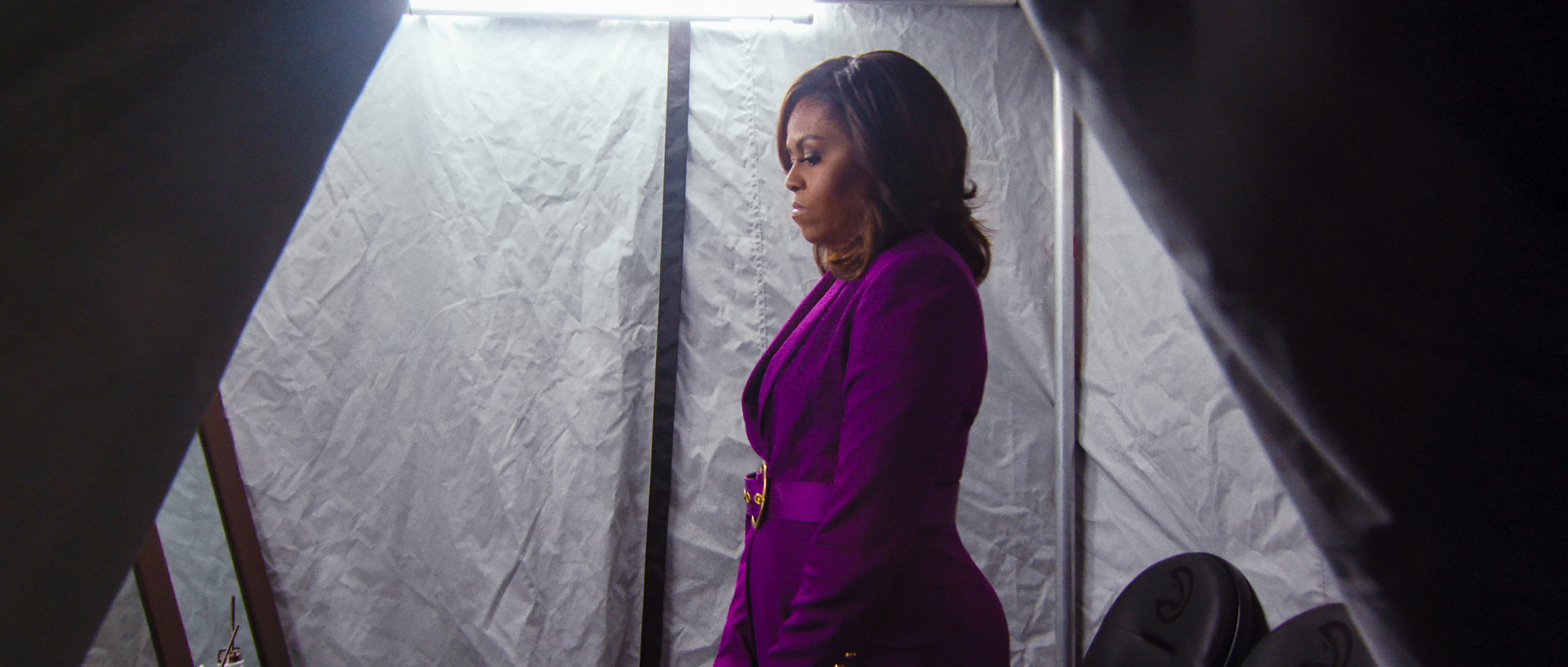

Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia, Sylvia Hamilton, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

o be a Black body in a predominantly white space often means being treated like you are invisible while in plain sight. This is something that the students in Sylvia Hamilton’s documentary short Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia (1992) wrestled with on a regular basis. Speak It! explores how the marginalization of the Black community within the education system has a lasting impact on society. While Canada has boasted about its diversity and inclusion for decades, the historical contributions of people of colour are usually omitted from the history books. As one high school student points out early in the film, despite Black individuals being in Nova Scotia for over 300 years, “you don’t find our statutes in the parks.” Hamilton’s film astutely shows that since most curriculums reflect white culture, and the teaching profession is still predominantly white, the erasure goes beyond the textbooks.

Like a stone that skips over multiple ponds, this cherry picking of whose stories get told also governs who gets to be viewed as the heroes. As Hamilton notes, the burden is often placed on Black individuals to educate their white peers, who benefit from a flawed system, on the racism they endure daily. Furthermore, Black students are frequently discouraged from pursing their academic dreams due to racial bias.

The frustration that comes with having one’s academic abilities questioned simply because of the colour of one’s skin is something that several young women express in Nadia Hallgren’s Becoming (2020). Though the film is an inspirational look at the rise of former First Lady Michelle Obama, it is also a reminder that, regardless of presidential titles, she is still a Black woman in America. She was not immune to the racial hardships that came with that realization. Obama laments in the film about being told by her guidance counsellor that she was “not Princeton material.” Not only did she go on to graduate from Princeton University, and from Harvard Law School, for that matter, but she also realized that many of her white counterparts in university were not any smarter than her. The message was clear that Black students needed to prove their worth, while the intelligence and ability of white students was taken as a given.

The misconception that those with white skin are naturally deserving of their placement in society can be traced back to slavery, but it took on a modern dimension with the invention of television. In Color Adjustment (1991), filmmaker Marlon T. Riggs documents how television from the 1950s to the 1970s was instrumental in perpetuating the notion of white perfection. Blacks were mostly absent from the idealistic utopia of happiness, peace, and success that television routinely constructed. The image of Black fathers was systematically excluded from family sitcoms until shows like Sanford and Son (1972–1977), The Jeffersons (1975–1985) and Good Times (1974–1979) arrived 20 years later. Their omission made it easier for white viewers to think of Black men as inherently violent animals rather than as caring individuals who shared the same values as them. The few Black faces that were able to grace the small screen were either presented as buffoons, mammies, or Uncle Toms who pleasantly lived their lives in a way that was non-threatening to the white community.

The constant promotion of a world that is comfortable and safe for white individuals ensured that the doors of opportunity were frequently slammed in faces of Black people. Riggs’ documentary dissects how this practice added to the struggles of the Black community, whose experiences, including the activism that was erupting in the streets during the Civil Rights Movement, did not fit the bland family-oriented version of America that television portrayed. Though series like Roots (1977) and The Cosby Show (1984–1992) were groundbreaking in their own ways, Riggs argues that neither really moved the racial needle. They merely portrayed Black upward mobility as being contingent on both white acceptance and the removal of their own Blackness in the process.

The complicated erasure of one’s Black identity when reaching a level of success usually reserved for white people is exquisitely captured in Ezra Edelman’s O.J.: Made in America (2016). It can be argued that the most fascinating aspect of Edelman’s brilliant documentary is not its stunning retelling of the “Trial of the Century” but rather the racial tensions that led up to it. The higher O.J. Simpson’s status rose at the predominantly white University of Southern California, and later in the National Football League, the further his Blackness faded away. Advertisers and those in upper society viewed him more as a white man who happened to be dipped in chocolate. He was not like those unruly Black individuals shown protesting against police brutality in Watts on the evening news. Being accepted by the white community was akin to receiving Willy Wonka’s golden ticket.

Simpson’s proximity to white culture afforded him a privilege that other Black athletes, several of whom risked their careers by protesting racial injustice and the Vietnam War, never reached. His wealth in the eyes of the affluent community that embraced him, and his own reluctance to be viewed as Black, created a barrier between himself and the issues impacting the Black community. His success was used to sell the misguided trope that if Black people just worked harder, they too would move up the social ladder.

Of course, it is difficult to ascend a social ladder that strategically has rungs missing. As is evident in Charles Officer’s Unarmed Verses (2017), there are often structures imposed on predominantly Black communities that rarely benefit those they were supposedly designed to help. The documentary focuses on the residents of a Toronto Community Housing complex known as the Villaways who are subjected to a massive four-year “revitalization” project that will see their homes demolished and replaced by condos. Of course, most of these individuals are from low-income households and cannot afford the shiny new residences allegedly built for their betterment.

Observing the beginning stages of the gentrification and relocation of a neighbourhood through the eyes of a 12-year-old Black girl, the film offers a stirring examination of how communities of colour are often forced further into the margins of society. Unarmed Verses finds hope in the ability of art to help Black youth find their voices while making it clear that the systems in place make their upward climb even steeper: the harsh realities of their circumstances remain clearly in view. One is constantly aware of how a person’s place of residence can govern how they are treated and the opportunities they are unfairly denied.

The ways in which one’s address can impact both the perceptions others have of you and your job opportunities is powerfully captured in directors Jennifer Hodge and Roger McTair’s piercing look at housing, racism and policing in the Toronto community of Jane and Finch. Their film Home Feeling: Struggle for a Community (1984) may have been released 35 years ago, but it sadly still feels extremely relevant today. Hodge and McTair expose two distinct worlds within a community that minorities are often forced to navigate daily. One is filled with numerous governmental policies that often keep people of colour in poverty rather than help to lift them out of it. The other is an over-policed environment where the mere sight of a group of Black teens hanging out is deemed as a potential threat to the public safety.

The fascinating thing about the policing of Black lives, as captured by Hodge and McTair’s lens, is the lack of accountability on the part of the officers who foster a cycle of fear within the community. The various officers interviewed, both white and Black, claim that they are the true victims in all of this. They are the ones being disrespected due to media-driven “exaggerated” accounts of their encounters with Black citizens. However, Hodge and McTair show footage that tells a different story. Whether it is the irate Black man, frustrated that officers are questioning him about the vehicle he has owned for years, which they naturally assume is stolen, or tales of police conducting illegal searches of apartments, Black life is frequently lived under an unforgiving magnifying glass.

As the activism within these documentaries shows, those peering into the magnifying glass often dictate the narrative they are willing to see. It is easier to ignore the hardships that Black people endure when the only meaningful interaction that one has with that community comes from the pre-filtered view of others. It is why the destruction of statues and brand-name stores, all things that can be replaced, receives more public outrage than the taking of an irreplaceable Black life. Whether it is politicians, law enforcement or media corporations, standing up for racial equality is often portrayed through the misinformed lens of disorder and violence.

In Stanley Nelson’s The Black Panthers: Vanguard of Revolution, his sprawling look at the rise of the Black Panthers in the Civil Rights era, the director captures the various ways Black activism is seen as a threat to white comfort. The mere image of Black men and women with guns peacefully protesting for equality evoked more unease than the images of Black bodies being brutalized by the police on the nightly news. The Panthers fought against systemic racism in policing, education, housing, and more, but it was their tough appearance that the media obsessed over. This opened the door for J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO program, which used ruthless and unethical tactics to systematically discredit the organization, to manipulate the media and paint the Panthers as “Black Terrorism”.

There are many parallels between how the Panthers’ narrative was co-opted with the ways that grassroots activism, such as what occurred in Ferguson, Missouri after Michael Brown’s death, is often portrayed. Providing the perspectives of protestors on the ground, Damon Davis and Sabaah Folayan’s Whose Streets? (2017) captures how law enforcement not only strategically blocked the public from the events surrounding the shooting, but also helped to dictate the media’s reporting of the ensuing protests. Reporters were blocked from seeing hours of peaceful protest, and the way officers antagonized the protestors, but had their cameras rolling when tensions boiled over and looting occurred.

Despite the blatant abuse of power displayed against protestors, including arresting them without providing valid reasons, Davis and Folayan’s documentary captures the persistence and ingenuity of this generation of activists. They use social media to organize and unite various members of the community. The filmmakers make it clear in Whose Streets? that this movement for equality is no passing fad. The film closes on a powerful image of two generations of Black women leading activists in chants that declare, “It is our duty to fight for our freedom … we have nothing to lose but our chains.”

It is often through the persistence of Black women that social change is achieved. Whether it is playing key roles in the Civil Rights Movement and the feminist movement or starting current movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, the extensive contributions of Black women are rarely acknowledged. In Dionne Brand and Ginny Stikeman’s blistering documentary Sisters in the Struggle (1991), Black women are shown leading the charge against the various inequalities in society, while enduring racism and sexism every step of the way. They are not only frequently overshadowed by their male counterparts in the media, but are often shunned by the white women who benefit most from their fights for gender equality.

Working long hours in jobs that often pay them less than their peers, the women in Brand and Stikeman’s film are constantly aware of the steep price that can come with activism. They are usually the first on the frontlines of the fight, often without the protective armour of privilege that allows white men and women to speak with impunity. However, for many Black women (and men), the stakes are too high to not stand up for what is right. They live in an unforgiving world that does not give Black bodies room to make mistakes.

Given the rigid expectations often placed on Black individuals, it is important that documentaries like RaMell Ross’ Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018) present a different perspective on Blackness. What make Ross’ poetically hypnotic film such an essential work is that it humanizes Black lives. While Ross includes moments of tragedy, and two subtle scenes that remind viewers of the policing of Black lives, he understands the importance of not letting his film be consumed by it. The film allows the Black experience to be beautiful, joyous, curious, and mundane. It reminds viewers of the humanity that others frequently strip from Black life.

As Black Lives Matter protests continue to erupt in the streets, it is important to remember that at its core is the plea to be treated with basic humanity. Through these and other films, Black filmmakers have continually shown that systemic racism and activism are elements interwoven into every aspect of Black life. If you only view the racism impacting the Black community through the context of police brutality, then you are not truly seeing why Black lives matter.