“You don’t show yourself, you conceal yourself. You conform,” says filmmaker Lixin Fan as he describes the collectivist ideology with which he was raised in China. Fan, speaking at the International Premiere of I am Here at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival, makes his film a fair counterpoint to competition shows like The Voice and American Idol. The director, who was born in Wuhan, China in the 1970s, sees a notable ideological shift between the youths of his generation and the young men he follows in his latest documentary. Fan provides the same subtlety of observation in I am Here that attracted ample acclaim to his previous docs Last Train Home (2009), which he directed, and Up the Yangtze (2007), which he produced. (Both films earned Genie Awards for Best Documentary Feature.) The openness and understatedness of I Am Here display more of Fan’s astute observations on a nation in a time of change.

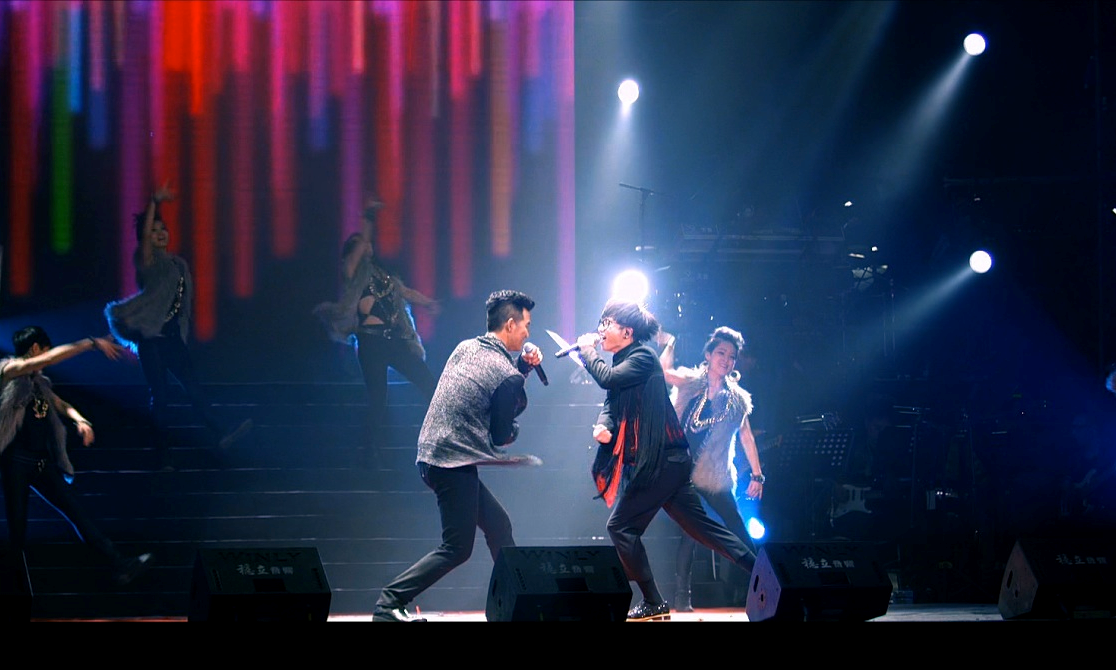

I Am Here conveys the greater ideological movement in China’s transition from the collective to the individual as told through the story of ten young men competing in the nation’s most popular televised singing competition, Super Boy. The ten contestants of Super Boy are an unexpectedly effective group of protagonists with which Fan interrogates the changing landscape of Chinese ideology. Super Boy marks a cultural significance for Chinese audiences because it offers, as Fan says, “a symbol of the democracy of entertainment.” North American viewers of American Idol and The Voice might take their voting privileges for granted, but Super Boy represents a relatively new Chinese phenomenon: the right to stand out from the crowd.

an explains that he developed this intuitive angle on the Super Boy sensation after the producers of the show approached him to make a behind-the-scenes documentary. The project would mark the ten-year anniversary of the grassroots singing competition. “I initially hesitated on documenting the Super Boy phenomenon after making films that take critical perspectives of contemporary China,” Fan reveals.

“My first reaction was, if it was going to be a propaganda film about the show, I’m not that interested,” Fan notes. “I kind of back-pitched them and said that the world might be interested in what kind of people might be ruling China in twenty years.” The rise in celebrity and instant fame associated with singing competitions around the globe immediately mark the Super Boy contestants as figures for the next generation. Whoever leads the next generation of celebrity-obsessed selfie culture to power requires a thick skin for living in the spotlight.

I Am Here makes the ten Super Boy contestants prime candidates for the job. The film reveals how Super Boy differs from its North American contemporaries in that it literally broadcasts the contestants’ lives 24/7, for the producers rig cameras around the so-called “Voice Academy” that houses the boys as they live together and prepare for battle. “It’s really an episode of The Truman Show come to life,” Fan reflects, as he remarks on the enormous pressure these young men willingly face to prove themselves China’s next top star.

The constant voyeurism into the contestants’ lives offers a wealth of material for which a documentary filmmaker often dreams. There is a challenge, though, in creating something valuable from hundreds of hours of fly-on-the-wall production footage. “The difference,” Fan observes, “is in the power of a camera held by a filmmaker versus one that sits fixed on the wall.”

Fan explains the layered effect of the film, saying, “The documentary camera is more of a look with respect and intimacy first… so we tried to be a sensitive camera rather than a machine on the wall. That way we were able to enter the characters’ minds, [who] they are, what they value.”

The approach lets I Am Here reveal both the public and private elements of the Super Boy challenge, as well as the personal and collective dreams the show embodies. Fan’s intimate perspective of the ten contestants reveals a side of the competition one might not expect. Rather than emerge as rivals during the competition, the boys become remarkably close as they share the quest for stardom with the nine other finalists (and the leagues of other entrants) in the show. Fan notes that the producers themselves were taken aback by the relationship of the boys that season. “They had never seen contestants become so close,” he adds.

It’s not really surprising to see such closeness between the contestants, though, if one situates I Am Here within Fan’s framework of the democratic evolution of China for this generation. The contestants, Fan proposes, “are products of a generation of Chinese youth growing up in an age of newfound individuality and freedom.” This freedom also comes with significant pressure in the era of China’s one-child policy. “Most of the kids come from one-child families,” Fan explains, “so imagine growing up as the only child. [They] don’t have people to hang out with, so the bond between the boys is very strong. They value their friendship.”

The single-child family dynamic also contributes to the pressures the contestants face on the show. Fan elaborates on the way the family planning policies become an unspoken element in the film, saying, “Most of these Generation Y kinds are the only children, and they face the pressure of a single child family. In a social media era, does it mean that they’re all very self-centered and fragile? Does the single child family situation enhance that?” These Super Boy contestants carry the dreams of their parents in addition to their own, all the while acting as mediated peers for the millions of young fans who see the stars as extensions of their own dreams and individuality. The hype and media frenzy of the show enhances the pressure to stand out from the group.

I Am Here reveals several collisions between the shifting ideologies as the Super Boy contest reaches its peak. One pivotal sequence sees the producers ask the contestants to confess to the camera the name of the fellow contestant they believe to be the weakest singer of the group. One contestant refuses to cast a ballot for anyone other than himself, and I Am Here finds a gripping level of drama as the audience becomes heavily invested in these contestants who prize the talents of their peers above their own ambitions. The defiance infuriates the producers, though, yet Fan notes that this small act of rebellion, “is a direct violation of the rules, but it seems that this Generation Y doesn’t give much concern to being obedient or following the rules. They think more independently.” Friendship trumps fame and fortune, even in the era of instant celebrity.

The disposability of such celebrity grants I Am Here much of its emotional drive as Fan accompanies some of the contestants outside of the glitzy studios, away from the spotlights and into tranquil settings where they may simply be themselves. Sumptuously shot scenes in the Gobi Desert create an image of expansive possibilities for these leaders of tomorrow, but they also capture the innocence of the young men growing up without much guidance from a generation of elders who are comparatively immune to their reality. Few pockets of China really seem to be invulnerable to the growing whiff of celebrity emanating from this democratic television show, though, for one brief but striking sequence sees the Super Boy contestants visit a house of “left behind kids” (children whose parents went to find work elsewhere). The younger children find themselves enrapt with the cameras and the aura of these boys, although they don’t seem to understand the value that the contestants supposedly hold. The telling sign, Fan notes, comes when one of the children asks for his signature in addition to those of the contestants. Holding a camera makes him someone of prominence, but it’s a foreign currency.

“What is an idol?” the kids ask as they collect autographs from the stars. The kids can’t even conceive of celebrity, for, as Fan notes, “the word ‘idol’ isn’t even part of their language.” The sequence reveals how no filmmaker, or individual, can necessarily escape the culture he or she critiques as Fan himself becomes an instant celebrity. “That’s really the advantage of a documentary film,” Fan says while reflecting on the unplanned moment that gives him his fifteen-minutes of fame. “All the material comes from reality and there are all these different levels of reality you can explore, image-wise, and if you present them in this complex way, you’re building this microcosm for the audience to try to understand or to compare what is this world that leads to experiences you have in your own world.”

The irony of Fan’s small moment of fame in his own film forms a necessary part of I Am Here’s ability to let the story of the boys resonate beyond their generation. Fan sees his own inescapable complicity in the currents of consumerism and globalisation circulating about the Super Boy phenomenon and, in turn, contemporary China. Being a part of the action allows oneself to be more than a distant observer, and the film reflects this subtlety by remaining respectful of the contestants’ personal space, but also by drawing the viewers into their personal and collective stories at various moments. “The act,” Fan notes, “is a lot like a relay race as the generations of the old and the young make sense of China’s future.

“I think there’s a very interesting generation gap between the two,” Fan says, “and what’s going to come out of that generation gap will really mould where China is heading next.”