Belonging

(Turkey/Canada/France, 72 min.)

Dir. Burak Çevik

A true crime story and a love story, Belonging keeps its main characters offscreen until well into the film at which point we see them played by actors. At the beginning of the doc, director Burak Çevik reveals how a woman named Pelin and her lover Onur drifted into a bizarre plot to murder her mother. A melancholic sense of not just doom, but absurdity hangs over the film. The murder could have been in a James M. Cain story, but the motives for it are vague. The couple doesn’t act out of driving passion or material need.

Moreover, Çevik is not simply telling a story he researched and found interesting. Pelin is his aunt, and the murder victim was his grandmother. In keeping with the movie’s aura of mystery and ambiguity, the filmmaker doesn’t entirely explain his motives for making Belonging in a voice-over black screen prelude. In interviews, he has explained that the events in the film happened fifteen years ago when he was ten.

Much of Belonging consists of shots of places linked to the story, which is told on voice-over: the exterior of an apartment building, rooms in an apartment, a rocky beach, the interior of a car at night, and so on. These places seem haunted by the people who once moved through them, and are now absent. The approach recalls the final sequence of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Eclipse: a montage of streets, buildings, and sensuous details connected to a couple (Alain Delon and Monica Vitti) who disappear from the movie.

The doc’s matter-of-fact narration is drawn from Onur’s court testimony. He describes how he met Pelin and agreed to help her kill her mother by recruiting a friend who seemed to have an oddly casual attitude toward murder. The method they come up with doesn’t quite make sense. Tension builds, you imagine characters and their actions, and then, things don’t go according to plan.

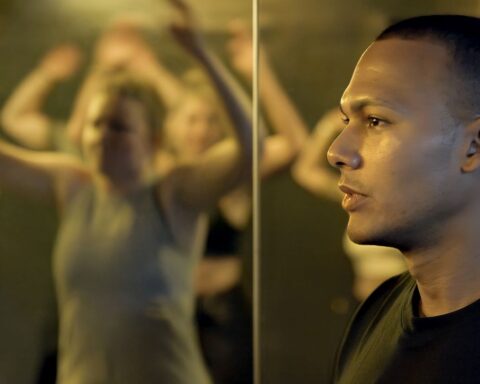

Suddenly, we see Pelin and Onur, (played by Eylül Su Sapan and Çaglar Yalçinkaya), as they meet each other for the first time outside a bar, and begin a tentative relationship. Like the couple in Before Sunrise or young people in an Eric Rohmer picture, they chat about random subjects. He tells her that he’s had happy by-chance events. She reads a long, free-associative stream of consciousness she wrote. He explains how to make a horse recognize you at its owner, and she seems to be interested.

At one point, Pelin recounts everything she did one day, including masturbating and writing to random people in other countries after finding their names and addresses online. At a climactic moment, Çevik cuts to the couple lying in grass, favouring intimate closeups of her face. They make love, and when they share a post-coital breakfast, Çevik focuses on neat plates of sliced tomatoes, cucumber, and olives. Pelin’s hands slowly and meticulously peel an orange in this hypnotic scene that obviously doesn’t jibe with a murder conspiracy.

Çevik doesn’t judge these people, nor does he dwell on violence. We know that both Onur and Pelin live by following where destiny takes them, and destiny can lead to disaster. Is that Çevik’s point in Belonging? Or perhaps, as in Camus’s The Outsider about a man who kills someone out of the blue and shows little emotion about his crime, there are no explanations for anything that has occurred.