There’s a reason why Fiddler on the Roof remains one of the most acclaimed and beloved musicals over 50 years after it debuted in 1964. Just look at the headlines made this week about Donald Trump’s latest Twitter rant in which he dubbed himself “the greatest President for Jews and for Israel in the history of the world” and likened himself to the King of Israel. One doubts that Tevye the milkman would have voted for Trump.

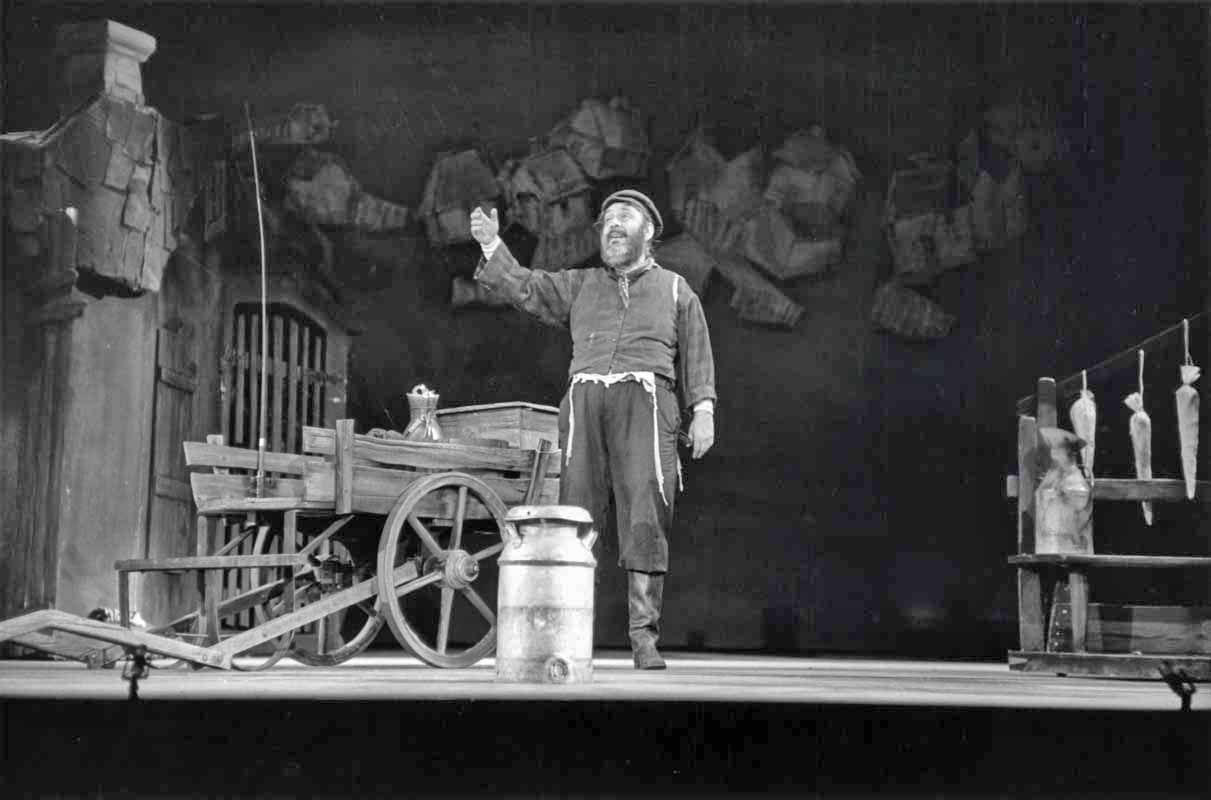

Max Lewkowicz’s documentary Fiddler: Miracle of Miracles assess the longevity of Fiddler on the Roof as it become more relevant than ever in Trump’s America. The doc looks at how the Tony-winning Broadway musical, Norman Jewison’s Oscar-winning 1971 film adaptation, and ensuing productions continue to inspire audiences with the story of Tevye the milkman who slaves to save his family in Czarist Russia.

Lewkowicz’s doc perceptively understands that the best adaptations are those in which aspects of contemporary life permeate the original text. The film puts Fiddler in conversation with the various currents of change and political forces that have kept it relevant since the musical’s inception. Miracle of Miracles assesses Fiddler’s origins from the stories by Russian/Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem that inspired the musical by Joseph Stein, Sheldon Harnick, and Jerry Bock, examining its evolution through the present as it travelled the world and touched audiences with its tale of the human spirit. The film features an impressive cast of talking heads, including Harnick, Jewison, Chaim Topol (who played Tevye in the 1971 film), Oscar-winner Joel Grey, Hamilton breakout Lin-Manuel Miranda (whose wedding rendition of Fiddler’s “To Life” was a viral sensation, and many stars from productions across the decades who speak of the show’s appeal and significance.

As proof of Fiddler’s ongoing appeal, Miracle of Miracles was deemed “The Chosen Film” as the audience favourite at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival when it premiered earlier this year. For the Montreal-born and New York-based Lewkowicz, the doc is an opportunity to toast “l’chaim” to a musical that has inspired him and influenced his own understanding of human struggles. POV spoke with Lewkowicz ahead of the film’s theatrical release.

POV: Pat Mullen

ML: Max Lewkowicz

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: How were you first introduced to Fiddler on the Roof?

ML: I was first introduced to Fiddler on the Roof when I saw the film in 1971. Then I saw the Broadway show and I’ve been a fan of it ever since. I had just finished a film in 2015 for HBO Documentary Underfire: The Untold Story of Pfc. Tony Vaccaro about a World War II photographer who became a great photographer, fought in combat, and then had PTSD and nightmares. I met Sheldon Harnick at a preview to the opening of the 2016 was revival at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. Sheldon and a lot of the cast and the director, Bartlett Sher, were there and I heard Sheldon telling all these stories about how Fiddler was first created as a Broadway show. I said, “Wow, that’s a story if I ever heard one.” I went up to him and I said, “Sheldon, would you mind if I interviewed you?” I didn’t know what it would lead to at the time.

POV: There’s such an impressive range of people featured in the film. What were some of the highlight interviews? Was anyone tough to land?

ML: Everybody who we asked was eager. We spoke to Bette Midler, who was working on Hello, Dolly! and was exhausted, so she didn’t appear in the film, but everybody else was very pleased to be part of it. Norman Jewison really understood it. He really, really understood what Fiddler was about and right at that point, 1970-71, the world was in the same sort of turmoil as it is today. We didn’t have the same President—they had Nixon, so it’s hard to say, which was the greater turmoil.

POV: The wealth of archival material in the film is extensive. What were some of your research strategies?

ML: We went to the Jerome Robbins Foundation at the New York Public Library. They were wonderful. Since he has no family left, they’re the gatekeepers of his archives. We dealt with so many different things for the photographs. For example, tons of photographs were at the New York Public Library, the Center for Music Theater, and various traditional sources. We worked with some of the original Broadway photographers, some of whom have passed, but their kids gave us their materials. A lot of research was done in terms of Playbills, etc., or was based on the stories posed by the individuals.

POV: One voice that really adds to the film is the rare recording of Sholem Aleichem. Where did you find that?

ML: That was at the Jewish Center’s YIVO, which is for Institute for Jewish Research. They have an incredible archive on 16th Street. I had worked with them before when I did films about the Holocaust, some years ago. I asked if they had any voice records of Sholem Aleichem himself. They said, “Yes, in fact, we do. We have him telling the story ‘I Were a Rothschild,’” which is what Sheldon [Harnick] based [the song] “If I Were a Rich Man” on. We have the original—it’s been transferred to digital from the original recording. It was incredible to hear it. We translated it and we had Steven Skybell who was playing Tevye, a wonderful Tevye—maybe the best—in Yiddish version in New York on Broadway. He sings “If I Were a Rothschild,” so it’s wonderful to have him.

POV: You have a great body of work that looks at history and particularly around the wars, but why is a sort of cultural text like Fiddler on the Roof an effective way to look at history across the age?

ML: The original Fiddler story was written in 1905 by Sholem Aleichem. He had such prescience in foreseeing what was going to happen in the future. World War I hadn’t happened; World War II hadn’t happened; the Holocaust, etc. and yet he would write these stories about this fictitious small shtetl Anatevka and Tevye and his daughters as they were dealing with poverty. Tevye was seeing his daughters trying to break away. They wanted to marry who they wanted to marry. He was a remarkable writer. They call them the Jewish Mark Twain. In fact, when he died in 1916, in New York, his funeral was the biggest funeral the United States had ever seen—250 000 people.

That was stage one we. I decided to break the story into three distinct parts, beginning with everything was happening in Russia in 1905, the Russian revolution, and the Tevye stories by Sholem Aleichem. Then you have 1964 in America when the show’s opening. All the interviews I got dealt with the same issues: Struggles with families, the breaking with traditions; America was getting into the Vietnam War. The music was changing in ’64. Suddenly, these guys decided to make a Broadway show about a Jewish milkman in Eastern Europe. They made this incredible body of music and stories that survived. That was stage two.

Then stage three was today—how do all the elements in the story relate to what’s happening today. It struck me how “Matchmaker” is about women’s rights and women trying to break away—in 1905, they didn’t have any rights. In 1964 , Betty Friedan had written The Feminine Mystique and women were marching for their rights. Today, the refugees are being kicked out of Syria and elsewhere. It’s the same thing over and over and over again. I wanted to link the two together over a hundred years to show how great art crosses geographical borders, crosses historical timelines, religions, communities, and everybody relates to it. Joel Grey has the great opening line of the film and says, “Everyone loves Fiddler on the Roof and everyone thinks it’s about them.” That says it all

POV: There are so many great personal connections to the story told in the film, so I’m curious: how does Fiddler relate to our family’s history and your life?

ML: I’m Canadian. I have my Canadian passport, so I can always escape to back to Canada if Trump gets a second term. [Laughs] But I’m the son of a Holocaust survivor. My mother was in Auschwitz. There’s one interesting room element in this story, which I kept in the film: Chava, the daughter who is marrying outside of the faith, and Fyedka [Chava’s husband] leave, and when they’re saying goodbye to her family, Chava turns to her sister Tzeitel and says, “Tell them we’re going to Krakow where people treat you better.” That line doesn’t have much meaning for some people, but for me and for certain people, it was like an instant jolt of electricity. My mother was from Krakow and if you think about these two young characters who are 20 years old in 1905, in 1940, 35 years later when they are 50, they’re doomed. They’re going to the gas chambers.

Joe Stein had been a wonderful storyteller who wrote the book [script] for the show. I asked his widow if he meant to put that in specifically because it’s not in the Sholem Aleichem story. She said, “I don’t know, but I imagine he certainly didn’t put it in for no reason.” He could have chosen London, Paris, any place, but he said Krakow, which is just a little distance away from the parents’ settlement. That connected me to the story. The show does not have any reference to the Holocaust except perhaps that one line—and I do believe it is a reference. The show was written in 1964, so audiences had just been through that and certainly Jewish audiences had been through World War II and the discovery of the camps in 1945. We’re talking only 20 years later and yet it is remarkably powerful that, as we say in the film, the shadow of the Holocaust looms over the whole story. That blend of darkness and light. Compare that today we have images of refugees and people being murdered—genocide—in the Middle East. Human beings don’t learn, so we have to keep pushing out these stories to remind people.

POV: The musical and the documentary really reiterate the point of tradition and look at how the old ways stay alive in new families, new communities. What elements of tradition do you keep alive in your life?

ML: In some ways maybe I’m old fashioned. My kids call me old fashioned. I do believe in tradition. I’m not a religious person in the sense that I only go to synagogue perhaps once a year, but traditions change completely and they always have to change. They have to be modified to what’s going on around us. But, for example, I still read books on paper. I don’t read a book on a screen. One could say that’s traditional because I like the feel of it. I still like to read the New York Times as a paper. I believe in the strength of the family and in love—maybe that’s my strongest connection to tradition. Human beings love each other, and hate each other, but mostly love each other. That’s the best tradition of them all.

POV: Do you think there are any musicals today that might

ML: Hamilton is certainly a remarkable Broadway musical and will be around for a long, long, time. But not Mamma Mia! Certain Broadway shows don’t have the same depth as Fiddler or Hamilton and are just on the surface. But I’m not being negative about Mamma Mia! Whatever. [Laughs]

POV: You mentioned earlier that the wheels sort for the film were in motion in 2016 but sort of at what point in 2016? Was it pre-election or post-election?

ML: It was definitely pre-election, but Trump is Trump now. We started to do the interviews in 2016 with Sheldon and various people. In this beginning, we were getting as many people we knew to tell stories about the making of Fiddler on the Roof. Then in 2017, when we were in production and we heard that they were blocking refugees again, I kept thinking of my mother being blocked. I try to understand what the difference when you look at Tevye as a hero trying to protect his family from the pogrom in Russia and Czar Nicholas, who was very anti-Semitic, and then look at a mother trying to protect her child from the violence in Guatemala or Honduras. What’s the difference? There isn’t any. They’re just trying to escape to give their children a chance.

I began to say, “Why is there so much hostility towards these poor people who are trying to just survive?” I realized that this film had to be a bigger story than just the show. It had to relate to today. In 2017, we completely built in the elements to connect to the modern story fairly easily. For kids who are performing Fiddler in schools today, I want our film to help them understand what they’re doing.

POV: As the musical has enjoyed renewed relevance in the age of Trump, it’s received reactions from people who feel inspired, while others say it makes them fearful to see Tevye’s resonate today. After making the film and looking at the response and the current context, do you feel optimistic or fearful for the state of things?

ML: I’m a born optimist. I always look at the glass half full and I believe things have a way of changing. I think art continuously pushes against evil and mediocrity. It may not be instant, we always want instant gratification, but positive that good people will pop their heads up, push things ahead, and constantly focus our eyes forward. As much as there are dark forces try to pull us back, like the people in Charlottesville who were marching with burning torches like they did in Nuremberg in 1933, there’s still enough people that turn against that. But then you get hit with tragedies like the mass murders in Dayton and El Paso. But we as human beings have to keep struggling. I believe good will beat evil but it’s a long and difficult struggle.

Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles opens in Toronto on Aug. 23 at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema.