British Columbia has been at the heart of a devastating public health emergency for many years. Before COVID-19, there was the drug poisoning crisis. Fentanyl and other lethal-drug-related overdose deaths claimed 2,236 lives in 2021, more than any other year on record and nearly 10 times the number in 2012. Ground zero for this crisis has been Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES) neighbourhood, an area many drug users call home and that has weathered issues of poverty and government neglect for decades.

New York-based Canadian filmmaker Colin Askey spent 10 years working in this community, with drug users, social service providers, activists, and harm-reduction organizations. Witnessing the critical grassroots work that was being done in the DTES, he wanted to shine a light on the frontline responders that had been largely ignored by media coverage. After several years of making educational videos about harm reduction, Askey decided to use the principles of observational cinema to allow viewers a different entry point into a community he knew and loved.

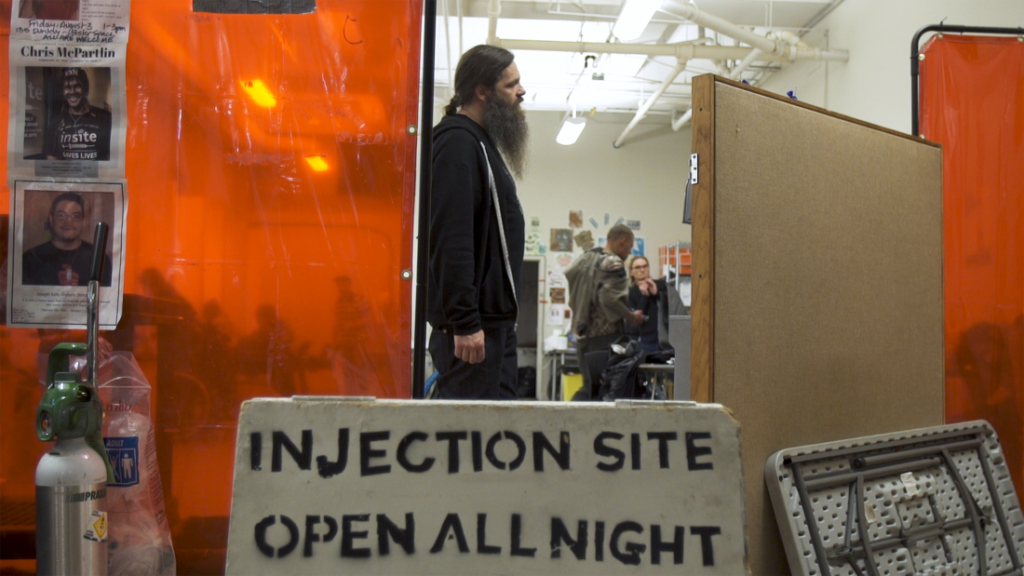

His 2019 short film Haven followed two trauma survivors and heroin users as they accessed medical-grade heroin (part of a harm-reduction approach called safe supply) at Vancouver’s pioneering Crosstown Clinic. In his first feature doc, Love in the Time of Fentanyl, Askey again uses an observational style to document the daily goings-on at the Overdose Prevention Society (OPS), a citizen-run site that helps drug users in the DTES inject safely, monitor drugs for toxicity, and learn about reversing overdoses. Love in the Time of Fentanyl follows OPS staff, volunteers, and community members as they discuss the radical power of harm reduction, demonstrate the care they hold for the space, and support each other through the burnout and grief of the overdose crisis. Shot largely in medium- and close-up shots, the film is intimate and revealing—quietly but firmly humanizing drug use and the people who engage in it.

Colin Askey spoke with POV about his intent in making Love in the Time of Fentanyl.

POV: Paloma Pacheco

CA: Colin Askey

POV: When did you begin making this film, and what was the impetus behind it?

CA: I began shooting it in 2018. When I moved to New York in 2016, it was right when fentanyl overdoses started going off the charts. I was going through the immigration process in New York and had to listen from a distance to what was going on [in Vancouver]. I’d worked in the DTES for many years. It’s a community that I care deeply about and really felt a part of, so learning what was happening was very difficult. Hearing about people being lost every week—people that I’d known and seen on the street every day passing away–and the friends that were working there, what they were going through, made me want to shine a light on what was going on.

The media was also coming out and talking about [the crisis] from the position of how hard it was on the paramedics—it was incredibly difficult and still is—and all the frontline workers. But no one was shedding light on the real first responders, the community members themselves, who were training themselves in how to use Narcan and oxygen to reverse overdoses. They were really the ones screaming and trying to raise awareness about what was happening down there and the effect it was having. So as soon as I was able to travel and to leave the US, that was what I wanted to capture.

For many years I’d done videos for the community and the harm reduction world in general, but they’d always been more educational videos to help amplify voices or raise awareness about harm reduction. I wanted to do something that could reach a wider audience. Having worked in [places like the OPS], I knew that not only do they save lives, but there’s just a beautiful kind of magic that happens inside them, where people who aren’t welcome in any other place in society are allowed to not feel judged and be themselves. It’s hard to describe the effect that has on people, and the relationships that are built inside these places.

For me, the original plan was to kind a fly on the wall and to do a study just on the space and what that space means to people. I knew lots of people that worked there and used the site, so I started following them and eventually it became more about a smaller group of people than the space. But mostly I just wanted to shed light on the scale of grief that was inflicted by this crisis in the community and the bravery of the response.

POV: You said that you wanted to be a fly on the wall and you’ve made that, an observational film. Having done previous work that was more educational, can you tell me more about the choice to make a film like this, and why you thought it might be more accessible to a wider audience?

CA: What I was doing before, they weren’t really films in the sense of things that would be watched in festivals. They were easily digestible for online, about one specific issue or a program that was at risk of losing its funding and needed a video to get funding. I reached out to [producers] Marc Serpa Francoeur and Robinder Uppal about a short film called Haven, asking how I could get the message out to a wider audience. Learning from and working with them opened my eyes to how to make this kind of films.

I think the observational approach was helpful because I’m so close to this issue and this community and feel very strongly about harm reduction and the availability of these services, so I didn’t want it to feel like [merely] a propaganda educational video. [Drug use] is still a very controversial issue to a lot of people and I think it’s misunderstood. I think the best way to combat something like that is to just allow an audience to walk beside, in a space that is rarely seen. Some of these sites are seen in news clips but there’s never really been a film that’s a day-in-the-life-inside-an-injection-site before. Because of my relationships with these people I had that access.

I’m hoping that an audience feels like they’re allowed to have their own thoughts and hopefully question their reactions to what they’re seeing; that it might shift the way people look at this issue and question the misconceptions they may have about drug users. And that they may be able to see that ‘hey, this is something that happens.’ People using drugs isn’t going to be comfortable for everyone, but they’re also going to see these same people saving lives and doing more for their community than I think most of us do on a daily basis. I knew I didn’t have to preach that. Because I’d worked in these spaces, I knew that would come across—or I hoped it would.

It was also a way of capturing [the life] and not being in the way. If I’d been running around trying to get people to say things or do what I want, it may have hindered the program. It was a lot easier to give people the idea of what I was doing and then allow things to happen naturally.

POV: A lot of the film takes place in a very intimate frame, with close-up shots of people’s faces. What kinds of conversations did you have with people about their comfort and consent to being filmed in these environments?

CA: There were a lot of conversations that happened before filming, and a lot of people that I’d known for many years before this. They were on board because of the work I’d done before. A lot of the close-ups that you’re seeing aren’t just because it’s important to see the beauty of these people and know that these are amazing human beings that we’re looking at it, but also to avoid others. There are a lot of cameras [in the DTES], so people are definitely not always cool with being on camera. A lot of it was actually about that—containing and making sure that we were not pointing towards anyone who didn’t want to be on camera.

Before I would enter any room—it was tough, because there were always people coming in and out, so I was coordinating a lot with the volunteers and staff—I would just make sure that anyone coming in, once I’d already started filming, knew what was happening. Before I started filming, I would go to each person in the room and say, ‘here’s what’s going on, and you’re not going to be on camera, or are you comfortable with your back?’ Those kinds of things. Just getting the full idea of what their comfort range was. And making sure that if anyone was uncomfortable entering that space with me, with the camera in the room, that that came first, and nothing would be happening that made anyone uncomfortable.

But I’ve worked in the community for probably 10 years, so I’d say that with half the people in the film, there’s a face recognition when they see me. That goes a long way. I never had any issues with anyone that didn’t want to be there because I was filming. Everyone was really collaborative and welcoming. It’s not easy, obviously, having a camera on you in such a stressful environment, but people were amazing. Not only just allowing me to be there but with sharing such vulnerable sides of their lives.

That’s the thing at the end of the day, what’s really going to help the audience—the risk and vulnerability people are willing to take to say, ‘I’m a drug user and that doesn’t make me a bad person.’ The willingness to show that and the bravery to do that is what will hopefully change a few minds about this issue.

POV: At one point in the film an OPS staff member says that so much of the time, drug users are not given credit when they find solutions. There’s the old activist maxim, “Nothing about us without us.” You’d been involved with this community for many years. Did you make any considerations about how you would include some of the participants of the film in the production of it, or allow them to have some say in how they were portrayed?

CA: One of the things I’d done in the community for a while was teach filmmaking in a place called the Drug Users Resource Centre [another harm-reduction site in the DTES]. At that place, I was teaching filmmaking with community members, so I’d worked a lot with trying to involve them in different projects. [On the set of Love in the Time of Fentanyl] I think just about everybody had a turn at holding the boom mic and helping out in different ways. I love doing that and people love being a part of it. So there were little jobs here and there. But also, at the end of the day, how they were represented was important for me.

It was especially important for me to show the people who were using on the screen how that looked. I never asked anyone to do it; it was always offered, to use. It wasn’t actually something that I was looking for. It’s something I’d always avoided previously but have learned more lately. A lot of people want to show the money shot of someone injecting and just that, which I think is wrong. But when you actually show the person and who they are and then that, it can be important. I think if we’re asking the audience to question their misconceptions and the stigma they may have towards drug use, we also have to be honest and say ‘hey, you may not be comfortable with all this.’ But what I hope is that people will question those reactions.

If someone were to watch someone injecting insulin, if they were diabetic, they may not like to see a syringe, but they certainly wouldn’t have the reactions they have to seeing someone inject heroin or fentanyl. I think it’s important to actually see. We may not like this, and we may not be comfortable with it, but I think it’s important to look at the reality of what that is. It doesn’t change that we also see this person saving a life and saying kind things and doing compassionate things for the community. It changes our perspective. And I hope that’s how audiences may look at it. But it was definitely important for me [and] for people like Dana and Don, who were using on the screen, to be able to see how that looked. Because that’s a very vulnerable, important moment and I wanted them to know what it was going to look like and how it was framed. So they were part of that process.

We also made sure that all the graffiti and stuff that was in the film—anything that the community members had created – was credited, and that people were paid for the work that was done.

POV: What does it mean to you to be exhibiting this film in 2022, a few years after you made it, when we’re still experiencing a drug poisoning crisis? What do you hope people will take away from the film in this context?

CA: The way I see it is that this community has been screaming for years about the solution. I’ll just focus on one of the evidence-proven solutions: providing a safe supply and clean injectable heroin. If you look at the history of, say, Vancouver compared to Switzerland, for example: When Switzerland opened their first safe injection site, they went fully on board with harm reduction programs and moved into safe supply and offering opiate-assisted therapy. Vancouver opened one safe injection site and harm reduction was really stalled. Partly that was because of the regulations Stephen Harper put on opening safe injection sites when Insite [Vancouver’s first supervised injection site] won in the Supreme Court.

We’ve had opiate-assisted therapy, but it’s all been studies on very small scales, which has never really been able to meet the needs of the [DTES] community or this country. In Switzerland, for example, right now you don’t see fentanyl entering the black market because there is no black market, since they’ve been providing clean regulated drugs to chronic drug users. There are barely any overdoses. People that have been using these programs have been able to find work and get their families back and lead healthy lives.

It’s been studied for years, but we as a society are comfortable with saying ‘no, that’s not right,’ and allowing this number of people to continue dying. At the end of the day, [our current] laws and policies are saying that if you use drugs, you deserve to die. The solutions are right there, and the community’s been screaming them for years, but efforts to provide them have been very slow.

It’s allowed it to get to the point now where some people are addicted to fentanyl. They won’t even touch heroin. You may have heard recently that they’re starting to offer fentanyl-assisted treatment, which is giving people at the only safe alternative to using black-market fentanyl. At least they know the dose and people who have been using fentanyl for years are not going to overdose.

We’ve been playing catch-up for years. It’s going to take for the decision makers and politicians to really mobilize and for us as a society to really look at this issue and open our eyes to the degree that it is affecting people. It’s not about fentanyl; it’s about the way that we view drug use and drug users—and our policies—that are killing people. We need to not only look at the way that we view this issue, but we also need to educate ourselves on the evidence and the studies and examples that are out there. I hope this film encourages people to do that.

Love in the Time of Fentanyl premiered at the 2022 DOXA Documentary Festival.

Update (11/14/2022): The film has its US premiere at DOC NYC.