On a cold day in December 2016 in Toronto, I headed into the apartment of Mandi Gray, carrying a used camera from Craigslist, a tripod, a borrowed lavalier microphone and a Zoom recorder. Gray was a month away from testifying against the man accused of raping her. She was frustrated and worried and wanted to document her struggles with the judicial system and law enforcement.

I agreed to come by and help her film herself talking about the trial, not realizing that this shoot would be the first of many over two years of chronicling her fight for justice, an effort that ultimately resulted in a groundbreaking human rights settlement. Nor did I realize that this would be the beginning of my first feature-length documentary film, Slut or Nut: The Diary of a Rape Trial, premiering this May at Hot Docs.

Gray, who likes to be referred to as Mandi in articles—“to show I’m a real woman and not just a color,” she jokes—greeted me at her front door in an old sweater and yoga pants, with no makeup on. Her fluffy, golden puppy, Cece, squirmed in her arms and nibbled at her clothes.

The day before our meeting, the Victim Witness Worker handling her case had called to let Mandi know that the accused had filed a motion in court to obtain all of Mandi’s therapy records to be used as evidence. The motion had been filed weeks prior, but no one had told Mandi.

“I’m always the last to know about anything,” she told me.

After being sexually assaulted the year before, Mandi enrolled in counselling for sexual assault survivors. Now she faced the risk that her deeply personal conversations with her therapist would be released into the public domain, read over and analyzed by the man who assaulted her and his lawyer, entered into evidence and possibly read back to her aloud in the courtroom. It could be used as an attempt to discredit her, and to prove that she was mentally unstable, that she was a “nut.”

On top of the therapy records, the Defense had also applied to question Mandi on her sexual history, to prove she was a “slut” and not a credible witness.

Mandi was tired and worried. Hospital records and legal books scattered the coffee table in her small apartment, as she searched for clues about what she might face in the upcoming hearing. I too had reported a sexual and physical assault to law enforcement, seven years prior. Mandi and I commiserated over shared negative experiences with the police, who treated us more like suspicious criminals when we reported than women in need of help. Unlike Mandi, I backed out of the case, fearful that moving forward would destabilize my already fragile home and work life. Mandi’s bravery to press the judicial system for justice floored me.

She planned to hire her own lawyer to challenge the motion for her therapy records. “It feels like I’m the one who is on trial,” she said.

“Women don’t know what they are getting themselves into when they report their sexual assaults to the police,” she continued. “If they knew, probably no one would ever report.”

We both understood the statistical chance of conviction in a sexual assault case was very low. Widely cited research by the YMCA of Canada showed that only three out of every 1,000 sexual assaults would result in a conviction. Mandi also knew that the chance of her assailant receiving a sentence longer than 18 months was close to impossible. Still, she wanted to press forward with the trial and waive her right to a publication ban so that her story could be heard.

Impressed with her openness, I suggested that I come with her to the trial days and record her experience. I did not know where the footage would go, but I knew the act of documenting would embolden her sense of agency in the process. Maybe we could eventually put it into an instructional YouTube series for other women to watch if they were facing trials themselves.

Mandi recorded her thoughts and feelings in written diaries, as well as video diaries she made on her laptop. I asked if she would let me see the video diaries and she agreed. These video diaries and her collages are now sprinkled throughout the film.

Shortly after our first meeting, Mandi introduced me to another activist, known only as Jane Doe due to a publication ban on her real name. Doe was raped at knifepoint by a man known as the “Balcony Rapist” in the 1980s. She learned that the police knew all along that the Balcony Rapist was targeting victims similar to herself in her community, but did nothing to warn her. She sued the Toronto police and, after 11 years of trial, she won and was awarded $220,000. Her case changed the law and mandated that police must issue public warnings of sexual assault predators.

On our first meeting, Jane Doe baked Mandi and I chocolate chip cookies and we sat around her fireplace chatting about what our footage might become.

“You have to make this a film,” Jane Doe said. “A radical feminist film.” She adjusted her black-rimmed glasses. Petite, but powerful, Jane Doe allowed us to video-record her and Mandi chatting for reference, but explained that we could only use her voice, not her image.

“You have to find a different way to show me,” She said. “Not some dark shadow. I don’t want to be a dark shadow.”

Mandi, Jane Doe and I brainstormed about what her image could be in the film:

“Maybe an alien? Or a space traveler from the future,” Jane Doe suggested.

“What about a white male cop?” Mandi said.

“We could have an actor play you.” I brainstormed.

“Ooh ooh.” Jane Doe said, “A fox. I could be a fox and I’ll wear a fox mask, because the media was always saying I looked foxy or cunning like a fox.” Indeed, I too thought Jane Doe looked somewhat fox-like with her auburn hair and angular features.

I filmed Jane Doe and Mandi for almost five hours, talking about the ins and outs of sexual assault, the criminal justice system, the media and the police. I quickly realized that Jane Doe was right: we should make a film, and Jane Doe’s writings and advice could narrate the story, helping to explain the more nuanced legal processes that Mandi was going through. I set off to figure out the best way to turn Jane Doe into a fox. We eventually settled on using a program called FaceRig, which created voice-activated animal characters. And so Jane Doe the Fox ended up narrating Slut or Nut, prepping Mandi for trial.

As the first trial date approached, nerves ran high. I warned Mandi that if word got around that we were filming, I could be ordered to provide the footage to the court. Mandi was willing to take the risk.

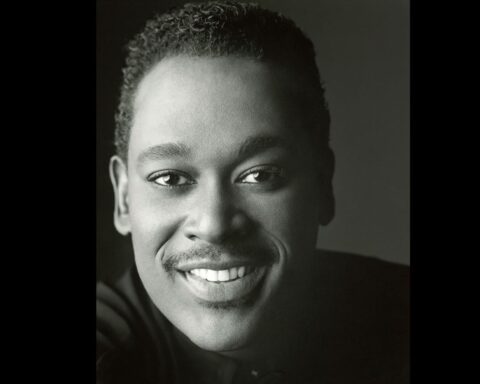

The high-profile case of talk show host Jian Ghomeshi started on the same day, in the same building as Mandi’s case. Suddenly the city of Toronto was obsessed with sexual assault, especially the Ghomeshi case. Hashtag justice movements like #WeBelieveSurvivors mushroomed. Protests erupted and supporters gathered, demanding justice. We filmed around the Ghomeshi trial as well and talked with the complainants.

Shortly after, however, Ghomeshi was acquitted from all charges laid against him. Meanwhile, Mandi’s accused’s trial continued for months.

With Ghomeshi acquitted, we ran into legal obstacles to using footage of him and his lawyer. I had to cut the Ghomeshi trial out of the film. Then, another woman we filmed extensively withdrew her consent to be shown in the film. She decided to report her assailant

who had begun stalking her and was now herself under a publication ban. Not wanting to lose her important story in the film, we decided to give her an animal avatar as well, like Jane Doe—a black cat, who we named Another Jane Doe.

I continued working closely with Mandi, in more of a partnership than a traditional director/subject relationship. We watched other documentaries on rape, like The Hunting Ground and Audrey and Daisy, and decided that we wanted Slut or Nut to steer away from any dramatic reenactments of the physical violence itself and focus on the survivor’s experience within the legal system.

As a survivor of assault, sitting through the trial and listening to the defense grill Mandi about what happened to her was exhausting. Creating the trial re-enactment in the film, reading the trial transcripts and watching the cuts over and over again drained me mentally. Rape myths from the defense attorney’s mouth echoed in my head before I went to sleep at night.

Not only did it trigger memories of my own experience, I also fretted about the possible repercussions of making the film. Would I walk down the street one day and see the accused following me? During a trial lunch break, he confronted me. He told me to stop filming. Another day he clenched his fists and growled at me outside the courtroom door. He was angry, whether outside or in the room with us. It was tense on the trial days, which stretched out for over a year.

I also worried for Mandi’s physical and emotional wellbeing. Facing someone with the knowledge that they are capable of violence, and that you are now a legal threat to them, is nerve-wracking.

As Mandi became better known and more visible in the media, our concerns for her safety during filming grew. A man ran up to us on the street and shouted obscenities. Comments online streamed with hatred for Mandi. YouTube videos with thousands of views popped up, calling Mandi a liar and insane and showing pictures of her over and over again. Mens’ rights activists sat in on the trial. People sent Mandi social media messages telling her that she deserved to be raped.

After gruelling days in court, we would come back to Mandi’s apartment together, eat chocolate cake and talk, share hugs, and discuss what dailies might make it into the film. Making the movie together made us function like a support group. Following in the tradition of participatory female documentarians like Barbara Kopple and Katerina Cizek, I wanted the survivors in the film to shape their own stories as much as possible. It was a way to shift their unpleasant experiences into something positive that other women could learn from.

Mandi suggested we add the art of Instagram illustrator Hana Shafi, AKA @FrizzKidArt. Her illustrations contained short messages that spoke to survivors of violence, urging them to persevere after abuse and to love themselves. Frizz Kid’s affirmative art is featured throughout the film to remind the audience that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to coping after a sexual assault.

The number of women working on Slut or Nut grew and we organized an Indiegogo campaign to finance the post-production process.

During gaps in the trial, I showed Mandi, Jane Doe and Another Jane Doe cuts of the film at my house. We bounced ideas off each other and talked about what was working and what we wanted to add to the story.

“We have to take this further,” Jane Doe said. “And add more about toxic masculinity. That is the real problem.”

Another Jane Doe commented after watching the final edit, “I love how you changed my voice. People think I’m a man in the film, and that is good, because this could happen to anyone and it can happen to men too.”

With Frizz Kid’s illustrations, the DIY-feminist collage imagery, and the animal avatars, Slut or Nut looked like young women had made it, and I wanted it to sound like young women too.

We met with Lora Bidner, an award-winning composer in her mid-20s to make the score for Slut or Nut. Over coffee in a small café on the west end of Toronto, Mandi and I gave Lora a list of Canadian female-led bands and songs we each liked.

“The music should be complicated and introspective, but not overly sad or sappy.” I said, “And we need anger. We need to feel Mandi’s rage against the system. The audience should walk away from this film pissed off.”

Lora tracked down nine different Canadian women musicians to add to the original score she composed for Slut or Nut.

Hailing from Winnipeg, Mandi’s hometown, female punk rock duo Mobina Galore opens the film with a raging anthem, “Spend My Days.” As the trial draws to a close, Vancouver singer-songwriter Willa wails,

“I’m not a trophy, a little Miss Bo Peep.

I’m not a sweet treat dropping from my feet to my knees for ya…

I’m not a swan, pretty in a pond.”

The music is angry and so are we—especially as the film ends and the audience realizes that hashtags like #MeToo and #WeBelieveSurvivors do not change the law, or the minds of judges, and that almost ten times out of ten, perpetrators of sexual assault still walk free.

Visit SlutorNut.ca for updates on additional screenings.

Read more about Slut or Nut in the feature “Docs and #MeToo” in our current issue.