Canadian Icon? Isn’t that an oxymoron? Is it possible this country has been the birthplace to great novelists, astronauts, scientists, filmmakers, athletes, poets and actors? And that we should celebrate them? Don Dixon thinks so. A photographer by trade and a patriot by inclination, Dixon’s slightly nerdish passion goes far back to his youth in a very exciting early Seventies Montreal and well into his many years as a go-to shooter of jazz musicians in downtown Toronto and actors at the Stratford Festival. Many years of commercial work in a studio in Toronto’s then-hip Queen Street scene reinforced his sense that Canadians can produce wonderful au courant work while also having a good time.

Then, Dixon had a revelation while having a family disagreement with his American sister-in-law about the birthplace of William Shatner. She said to him, “You know, William Shatner is from New York City.” Dixon recalls replying, “No, no. He’s from Montreal.” But she insisted he was a New Yorker. So Dixon just thought, “Oh well, she doesn’t know.”

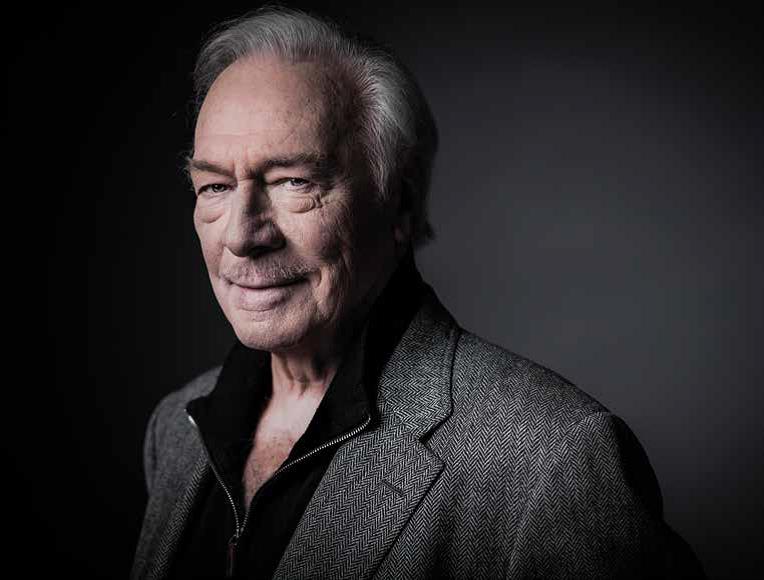

Dixon continues: “I came back to Canada and started telling friends about this conversation and was really shocked to learn that even a lot of Canadians don’t know that Shatner is Canadian. I thought everybody knew. When I had been talking to my sister-in-law, I had said ‘Well, what do you think about Christopher Plummer?’’ She said, ‘Well, he’s British’ and I said, ‘No, no. He’s Canadian too. His great-grandfather was prime minister of Canada.’

“She had no idea, but then I told the same story here and everybody I talked to thought Christopher Plummer was British too. Nobody knew his great-grandfather, John Abbott, was prime minister either. I thought this was really a sad statement about Canadians. We don’t even know who our stars are.”

Dixon thought long and hard about Shatner and Plummer and the ignorance of Canadians about their stars. Imagine if Matt Damon’s great-grandfather was another New Englander, President Calvin Coolidge. Wouldn’t everybody in Boston know? Canadians, he realized, needed to be cajoled into an appreciation of their stars.

The photographer approached his favourite coworker with his idea. “I’ve worked with the same makeup artist for over thirty years—Meliase Paterson,” recalls Dixon. “I said to her, ‘Meliase, why don’t we start a project where we’ll photograph famous Canadians and do an exhibition or something?’ She loved it and that’s how it started.”

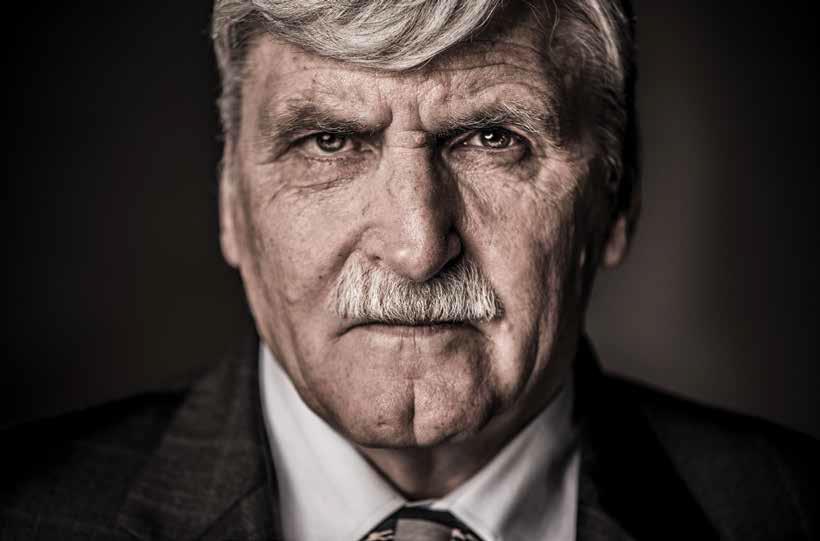

Dixon began shooting Canadian icons in the entertainment field, his field of expertise. Quite soon, he expanded his choice of subjects to include astronaut Roberta Bondar, marathon runner Donovan Bailey and General Roméo Dallaire, acclaimed for his role in trying to stop the Rwandan genocide. Eventually, he found another collaborator, Jenny Wells, who came on as executive producer, to bring in more Canadians deserving of the Dixon celebratory photo treatment.

His shooting is thorough; you can see profiles of his subjects in poses ranging from full face, staring into the camera’s eye, to a shot from a distance, offering a full body to express an icon’s personality. Dixon doesn’t choose one style. His artistic practice is one of exploration: he wants to know what makes people tick. His work is based on discovery and when he catches someone’s soul, he stops.

“I try to find that picture that sums up who they are in a true way,” says Dixon. “Sometimes I get it and sometimes I don’t. With Robbie Robertson [whose shot by Dixon graces our cover], his people said, ‘We’re going to give you twenty minutes,’ but after we started talking, it stretched out and Robbie said, ‘Well, I can hang around for an hour.’ The session went on for about forty-five minutes when I said, ‘OK, Robbie. I’ve got it.’ And he said, ‘What?’ I said, ‘Well, I got the shot. I’m not going to keep you hanging around here and just shoot for the sake of shooting. I got what I’m after.’”

Dixon’s favourite camera is the Nikon, famously used by Steve McCurry in his Afghan Girl portrait and by Nick Ut in the shocking picture of the young girl running, burnt by napalm, in the Vietnam War.

Says Dixon, “I’ve been a Nikon shooter for most of my career. They just keep getting better. I’ve had the bigger ones that I’ve used for advertising, but usually I use the small, compact ones. Really, it doesn’t matter what you take a picture with. It’s what you see that counts.”

One of Dixon’s finest subjects was Christopher Plummer. “I read Plummer’s biography just before he came to the studio,” recalls Dixon. “He described the view from his great-grandfather’s cottage, looking out on Lake of Two Mountains, which is across from Hudson. I’m from Montreal and realized, ‘I know where that cottage is.‘ I asked Christopher, ‘Was it on Île Bizard?’ and he said, ‘Yeah.’ Then I said, ‘I used to ride my motorcycle out there and sit on the edge of your grandfather’s house and watch the sun go down.’ We were buddies from that point on.”

Plummer loves dogs and made friends with Scruffy, Dixon’s dog. “Plummer invited us—my wife was with me—to his show that night,” says Dixon, “and put us right in the very centre. At the end of the show, he invited us back stage, and when we got to the dressing room door, his wife opened it and said, ‘Oh, you must be Scruffy’s parents!’”

Dixon and Dallaire had “an instant connection,” according to the photographer. As army brats, says Dixon, “We both knew what growing up was like for each other. Conditions are all the same—the schools, the places you live in. You’re constantly moving.

“When we got into the studio, Dallaire felt very fragile, uber sensitive to everything around him. He was just so alive and focused on every single thing, which was really inspiring to see.

“I got him in front of a camera and I didn’t ask him about Rwanda. Instead, I asked what he was doing now. I could see there was a big sense of relief when I asked that. He said, ‘My goal is to get children off the battlefield.’ And I said, ‘How do you do that?’ He replied, ‘When you put a woman on the battlefield, they’re the last person that will get shot. Children will not shoot at a woman. The idea is to get more women, visually with these children, and then if they’re not shooting them, we can take them off the battlefield, deprogram them and de-escalate.’ I thought, ‘Wow! What a great thing to be doing, especially after what he’s been through!’”

“Margaret Atwood is very inquisitive. She pulls no punches. She’ll look you dead in the eye and ask questions. It seemed that Atwood was actually more interested in interviewing me than being shot. I finally said, ‘Hey, wait a minute. I’m supposed to be taking your picture.’ I found she went from hot to cold instantly. She’d be very friendly and engaged, and then you’d hit on a subject that she was not so keen on and she’d get angry right away.”

“From the start, [Alanis] was so composed and very elegant. I found that in her speech as well. I asked, ‘What kind of films do you make?’ And she said, ‘I make documentary films about First Nations life.’ I asked, ‘What aspect?’ and she said, ‘All aspects!’”

***

“D’bi is a powerful lady. She started a program to raise money for grandmothers of children whose parents had died from AIDS. She’s also an actress and a poet. She’s very witty, very intense and very warm. When she came in to the studio, the first thing she did was hug me. She’s a little person with a big bear hug. She’s a big supporter of transgender youth and Black communities.”

“Measha and Meliase hit it off, big time. I just put a little stool beside the makeup chair and listened and watched. I like to see a character developing when I’m not engaging directly. Meliase is so engaging and people trust her right away. By the time Measha was on the lounge chair, we were friends.”

Dixon had shot Chuvalo ten years before the Icons series. After the shoot, he offered to take the great boxer to get his passport renewed. “We’d had a great interview and shoot. He’s had such a tragic life,” recalls Dixon. “We got to the passport office at 1:30 and there must have been a hundred people waiting in line. An hour later, we finally got up to the lady at the counter. She said, ‘You’re George Chuvalo! My son’s a boxer. Could I get your autograph?’ He says, ‘Yeah, do you have a piece of paper?’ So she gives him a piece of stationery and he starts writing a letter to her son. I was saying, ‘C’mon George, we’re holding up the line.’ But he kept on writing until he finished the letter and she said, ‘We love you, Champ!’ Then she asked for his birth certificate and George put his hands in his pockets—his hands are like Christmas turkeys, the biggest things I’d ever seen—and he tried to pull out his wallet but it’s the size of a softball and he can’t get it out. I said, ‘George, let me get it.’ I pulled out this giant wallet, and it’s got so many pieces of paper, it looks like kindling for a fire.” But the certificate wasn’t there. “So I said to the lady, ‘Well you know it’s George, can’t you just do this?’ and she said, ‘No, I’m sorry, but he’s going to have to get his birth certificate.’” After an adventure finding an Internet connection to verify his certificate, Chuvalo got his passport. And Dixon had a friend for life.