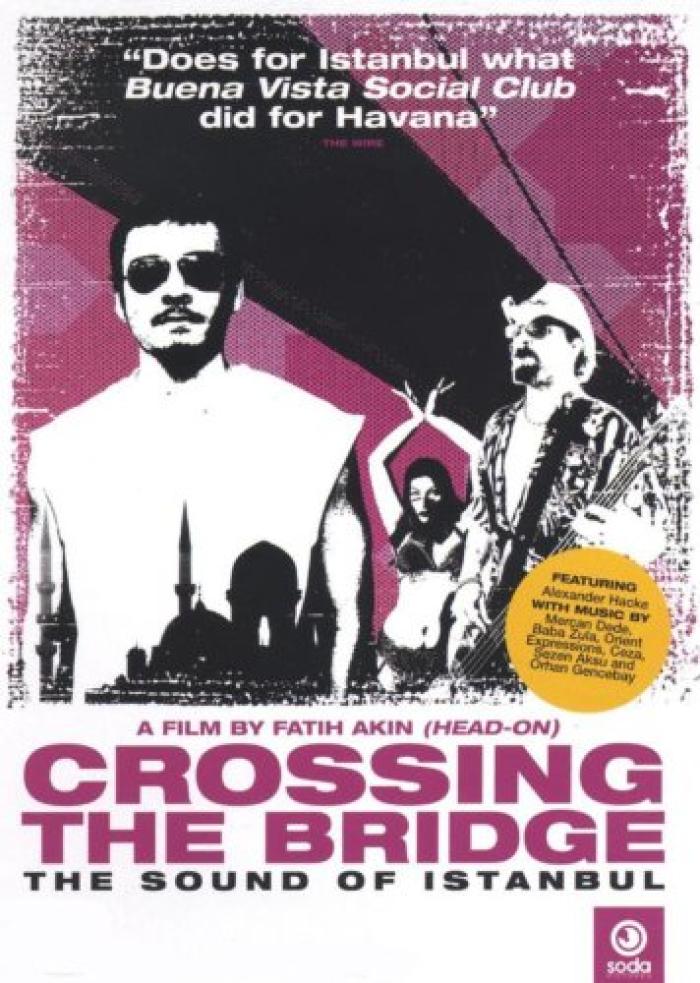

In the mid-2000s, Fatih Akin was at a crossroads. The Hamburg-born filmmaker had just triumphed with Head-On, which explored the German-Turkish community. Its tale of a complicated marriage alliance received raves, including the Golden Bear at the prestigious Berlinale. Financially, Akin was strapped after the film’s release, and he set his eye on fully exploring his Turkish roots, heading to Istanbul along with Alexander Hacke, Einstürzende Neubauten’s bass player, in order to explore the burgeoning music scene of an increasingly liberalized ancient city.

The resulting film, Crossing the Bridge: The Sound of Istanbul (2005), serves as both a remarkable time-capsule and cautionary tale, documenting the sense of optimism in the city that would be trampled by reactionary political forces only a few years later. When it was originally released it was a welcome musical journey, while nearly 20 years later, it’s even more powerful. It’s a statement about how the merging of musical expression from the many communities that make up a storied land can, when given the chance, create a beautiful, harmonious community.

Newly restored in 4K, and soon to be distributed by MUBI with possible theatrical runs, it played in to a mostly foreign crowd at the Red Sea International Film Festival in Jeddah where Akin was also on the Shorts jury. It was clear that the images captured remain both intimate and visually compelling, while the electrifying musical performances showcase a wide range of genres and expressions that speak to the multifaceted nature of the city.

The metaphor of the bridge physically connecting continents and cultures runs throughout the documentary, and while there’s much that makes the modern manifestation of Turkey feel heartbreaking, the film is a witness to a recent time when there was a sense of hope. With this film finally returning to form after being locked in battles between producers and music clearance negotiators, and given all that is going on both in the Middle East and around the word, the sheer joy of free expression captured in the films makes for an energizing, immensely satisfying experience.

POV spoke to Akin at the Red Sea festival following the premiere presentation of the film’s restoration.

POV: Jason Gorber

FA: Fatih Akin

The following has been edited for clarity and concision

POV: It’s back 2004, you’ve just won a little award at some local film festival called the Berlinale, and you’re now this international sensation. You choose to go to Turkey to do a movie about music. Tell me about that journey and what it was like going back at that particular time.

FA: Doing those films in that period – Head-On, Crossing the Bridge, The Edge of Heaven (2007), and later on my documentary about garbage, Polluting Paradise (2012) – these involved my discovery not just of Turkey as my motherland, but discovering The Matrix in a way. I was born and raised in Germany, living and socializing there and very much in the German film world. Doing those films really helped me to discover another universe. Making these films helped me discover different literature, different theatre plays, different movies, and, most of all, different music.

POV: It is easy to think of you living in Germany, growing up in Germany with this idea of what Turkey is. The reality of Turkey during that period is so unique and you articulated the changes that were going on—the brief window of openness. Did you get a sense then that it was something that was going to be sustainable, or did you feel it was going to continue to be fragile?

FA: I got the sense that there was something really powerful, a pioneering feeling of change. I was well aware that the country has a complex history. It’s a difficult global spot, it has a different past, a different religion. Growing up as a Turkish child, you know all about this.

POV: Yet there’s always an external romanticization of the place, the idea of Turkey. When you’re on the streets of Istanbul, it’s got to be different, but it’s also in some ways got to be more beautiful because it’s real.

FA: It’s not just the beauty of it. What I had discovered was the rock and roll of it all. Rock and roll is not really something that my parents taught me about Turkey, and it’s not something the newspaper taught me about Turkey. In that period, rock and roll just came out of the underground. I think it was 1999 that was the first time I was in an Istanbul rock club. For me, it was so beautiful to see people who looked completely different. When you went into a rock club in Germany in the mid ’90s or early ’90s, the period of grunge and stuff, you only saw Caucasian people. I would not see Middle Eastern people at all. But coming into this world in Turkey, a world celebrating rock and roll, and they all look like they’re from the Middle East? That’s different, man. That’s something else. There were Middle Eastern women listening to Helmet, right? Or Jane’s Addiction. That was something else.

POV: The central metaphor of a bridge is so redolent of everything the film is. It’s literally bridging the Bosphorus, seemingly between the two different worlds of Europe and the Middle East. As obvious and overt as that metaphor is, it’s almost easy to underplay how the deep levels of bridging take place. At a time when we talk about authenticity, about appropriation, about these words as if culture somehow is from one place alone and was birthed there without any influence from anywhere else. You go to a place that has “appropriated” rap and rock and roll. For you, musically, how did it reshape the way that you listen to music? These bands that you heard, did they change the way that you hear beauty in a way that you didn’t experience it before?

FA: Of course. They blew up my mind. They had parts of Western music and tunes I knew about, I’d grown up with, through the radio, through my records, which were, almost all of them, Western music, American music.

POV: Which music were you listening to when you were in high school?

POV: Which music were you listening to when you were in high school?

FA: I was listening to Prince, and I still do, you know.

POV: Another guy obsessed with bridges, I will point out.

FA: When I discovered Prince for the first time, it was during the Purple Rain era when I was 10. I heard it on the radio and I recorded it on tape. I would listen to the songs I recorded again and again. The first record I bought was two years later as Parade on vinyl. That is a very electric album for someone who’s 12. My classmates were listening to different music, British pop like Stock Aitken Waterman. For them, Prince was very foreign and very annoying. But when you discover the world of Prince, you discover metal music, hard rock music, Little Richard, African American soul, rhythm and blues, and all of that.

In the ’90s, of course, like anyone else in my generation I was listening to grunge, and then started listening to stuff like Helmet, Jane’s Addiction, Suicide Tendencies, and Soundgarden.

POV: 10 years after that, you’re in Istanbul listening to people who are influenced by those same things, but also influenced by more “traditional” sounds of the region. You actually have people on camera talking about non-Western time signatures, the skipping of beats because the dances are different, the rhythms are different because the physical movement is different in that region.

FA: Yeah, which is a groove. And it’s a completely different groove than the groove Bootsy Collins had. The Bootsy Collins groove is all on the first beat and it makes you dance. But in Turkey, there’s is a completely different sense of musical mathematics. It’s still funky and it’s still groovy, and it still makes you dance.

POV: How much did you know about these particular musicians when you got there, and how much of it was discovery in the sense that, when you were there, one group led to another group and led to another group?

FA: The first Turkish music I really was consuming by myself, was the music of Sezen Aksu who is the climax of the film. Ceza, the rapper, says she’s like a childhood memory, like Mickey Mouse or Jackie Chan. Her music was always there. When I was a teenager, and like every rock and roller unhappy in love, and that my love was not accepted, it was the music of Sezen who could console me the best, sometimes even better than Prince. For even the hard core rappers or the metal people, or the traditional people, or religious people, Sezen Aksu was like the connecting point: She was the bridge.

POV: In the movie, you have these 20-something kids who are listening to hip hop, doing rap, and they’re talking with nostalgia about her music and about how much her music means to them. You capture a moment where people were not afraid to do something that maybe might cynically be thought of as “old people’s music,” or the parents’ music. Do you think that’s still the case? Do you think that people who are doing hip hop or listening to them are simply referencing music of the last 20 years?

FA: I think it’s shifted. The music of 20 years ago is the music of crossing the bridge. The musicians of today have to be influenced by the musicians of crossing the bridge and I’m sure they are. I think Ceza created a whole scene. He was one of the first hip-hoppers who was that successful. You hear the influence of bands like Replikas, who were influenced by and produced by Sonic Youth.

POV: Who themselves were influenced by The Stooges, who were influenced by the Ramones, who were influenced by The Beach Boys.

FA: Right, and by Little Richard.

POV: We’re all on bridges! Just as Turkey has become conservative politically, musical expression has become conservative because exploration is minimized, and you are allowed to live in a silo now where you listen to what is fed to you by a custom algorithm. When young people come up to you, do they have the same sense of exploration, the same sense of making the effort to cross bridges?

FA: I think they do, and they do it on a very different level. Turkey and Germany are very different systems. The technical progress I have witnessed since Crossing the Bridge is dizzying, with AI and that stuff. My children consume music very differently. I try to teach them the record player. For them it’s too complicated, all of the vinyl shit.

POV: What is their connection to the old?

FA: They don’t have it. I am their connection.

POV: The rappers in the film speak reverently about their parents’ music, and accept that their music is influenced by what came before. I think, in some ways, that has diminished in newer generations.

FA: Let’s give it some time. My kids listen to stuff that is very different from what I was listening to. The hip-hop has changed. There is this kind of trap beat, and it sounds so different. There’s a genre in Germany called Cloud Rap – people do it by themselves on their iPhone, and it’s just silly music, but it’s their culture. It’s their sort of Beatles. When I say, “What are you listening to, what is that crap?” I think the parents of people who were listening the Beatles and Elvis Presley said the same thing. I don’t want to be like that. I want to stay young in my mind, and I actively try to understand it.

POV: So how have things changed from the music scene in Turkey since your film was made?

FA: A conservative force took over. They closed clubs, and they closed off concerts, and they forbade sponsorship from alcohol companies because beer brands cannot support bringing in Iggy Pop and The Stooges anymore. When you have such a censorious force, an underground is automatically building up as a form of resistance. And it is there in Turkey right now.

POV: If you put up a boundary, somebody’s going to want to put a bridge over it.

FA: They are there, they have to hide more. They have to go deeper into the underground. That’s why it’s called underground, because it has to be hidden.

POV: Let’s talk about the difference between fiction and non-fiction. How different do you see making a documentary versus making a fiction film?

FA: Documentaries are more fun, by far. The greatest thing about doing a documentary is that you are not the chief of it all. The randomness, the destiny, the momentum is in charge. You don’t create a reality, you try to catch it. You’re more like a hunter. You need a lot of patience and time, a small crew, and be quiet, and at the right moment, you have your material.

I truly love editing documentaries. I love also editing films, and maybe that’s the most fun part of the whole thing, in both genres. But documentary is like a piece of a puzzle, and when you do a fiction film, you have 1000 pieces, and when you have the puzzle of a documentary, you have 10,000 pieces. And if you like puzzles, you enjoy it more.

POV: Hypothetically, with a fiction film, you know what the front of the box of the puzzle looks like because you have a screenplay, but in a documentary, you’re trying to put puzzle pieces together and you don’t know if any of them are going to fit.

FA: Right. So, in a way, I love jazz and listen to a lot of jazz, and it’s always inspiring. If you compare filmmaking with making music, documentary, for me, comes closest to jazz.

POV: What jazz do you listen to?

FA: I like world jazz, jazz from Africa, jazz from Asia, Indonesia, but the thing I can always listen to is, of course, Miles Davis – early recordings, later decades, it doesn’t matter.

POV: Like with your love for Miles, this documentary is about eclecticism. We have an idea of what Istanbul is: We think Istanbul is going to be X, and you show us that it is not only A-Z, but sometimes Z is playing songs from B, and C is playing with songs from F.

FA: Exactly. The documentary is a deep reflection of me. I chose to focus on these musicians, not just in terms of whether I like their music more than other music, but because all of them were expressing different parts of myself. Duman is the hard rock inside of me, which is more the commercial side of me. Replikas is more the avant garde rock, which is also inside of me. Hip hop is strong in me. But Müzeyyen Senar as well: that was the music my mother was singing while she was cleaning when I was a child.

POV: It is strange that this film has been not seen for many years, you talked briefly about rights issues, restoration. We have a brand new restoration: MUBI has it?

FA: Yeah, MUBI. It’s a great company.

POV: I’m personally grateful I saw it now. Because I think at the time, I would have been too close to it, and now, by looking back at it, I get a better sense of what was taking place there. How has the film changed for you?

FA: I was surprised how well it still works. The other day, I saw Head-On, and it’s still ok, but I would do it differently today. It’s old. But Crossing the Bridge still works pretty well. I was surprised. Dome parts even work better.

POV: I understand there was some turmoil that lead to you even making this film in the first place.

FA: I had a fight with the producer of Head-On and, like the Turks divided Cypress, I had to divide the rights to protect it. I founded my company, and put all my fees from Head-On into it. I had to use my own money to finance it, and that ended up being my share. So I was completely broke, and the company was broke, and we needed desperately a film, so we came up with this idea of a music documentary.

POV: Your film exposes the futility of criteria, the futility of creating gaps when everything could actually be brought together. For me, this is why it’s actually extraordinary. What does it feel like when you watch it now after all of these years? What was your emotional reaction?

FA: I don’t feel sad. I don’t feel nostalgic. And I expected to feel like that.

POV: You are not mourning a lost period from that country?

FA: I learned so much watching it right now about everything: about biology, physics, society, sex, whatever. You have a society or an individual and it’s growing and it’s rising and it’s hopeful and it’s shining and it will flow and everything will become better and, suddenly, it’s collapsed so hard. Anything can happen. That’s what I felt on the one hand: Look where we are going and where we end.

POV: We’re in Saudi Arabia…

FA: Yes, we’re in Saudi Arabia. When I did the remastering, I said, “This has to be shown here.” I could have waited for a different film festival. I could have waited for Thierry Frémaux to show it because it originally had its world premiere at Cannes in 2005, a year I was also on a jury. Given its subject, I had to show it here. I was a bit upset that so few Saudis came. Last year, when we were here together, this pioneer feeling I had reminded me of what Istanbul was like back when I made the film. I thought I had to show it here as a kind of warning.