The dance doc has made significant leaps in capturing and controlling a moveable art form, from modern to ballet to the folkloric movements of a nation. As Danish filmmaker Boris Bertram discovered while making his new dance film, Tankograd, directors must become choreographers of sorts…and the best shots come from learning how to dance along.

“I wanted to tell a story about a Russian dance company in the most radioactively polluted city on earth,” says Bertram about the initial seedling of Tankograd, his latest documentary film. The film is set in Chelyabinsk in West Siberia, home to one of the most hazardous nuclear disasters on earth—20 times worse than Chernobyl! And at the centre of this omnipresent danger, a passionate modern dance company is coping with their city’s devastation through their art form.

In Tankograd, Bertram tells two stories, maintaining a rhythmic balance between history and art, with themes from the latter connecting with the facts about growing up in the ill-fated city of Chelyabinsk. What does art mean to the young Russian generation of artists and workers? It means an escape. It means staying focused on their form to distract from the realities of what is potentially a risky and short-lived life. In the film, one dancer accounts for Russia’s three major setbacks: poor roads, idiots and drunks. “All countries have problems,” she says, “but as long as you ignore them, life is beautiful.”

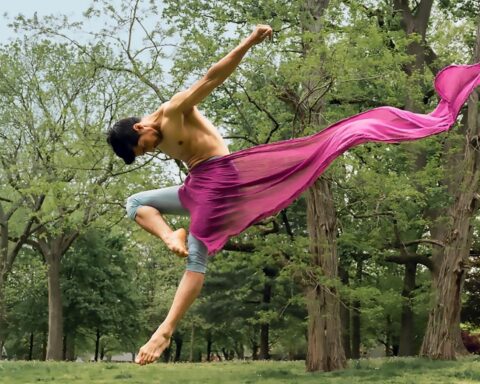

Ignore them, or perhaps interpret them. Previous performances from the Chelyabinsk Contemporary Dance Theatre have opened under such titles as The Dying Generation — considering the history of the Soviet Union, by abstractly conveying the particular themes of destruction and corruption. Tankograd’s final dance performance is a weightless piece called Celestial Bodies, which explores the notion of an absence of gravity, both conceptually and as one who lives in Russia. As Bertram sees it, if a person loses his footing in Russia, he falls hard and, without a defined support system, might face tremendous difficulties rising up again. Celestial Bodies incorporates themes of attraction, free fall and flight, while using motifs of rocket ships that mirror atomic bombs, thus reflecting their city’s history through conceptual movement.

By the time we see the final staging of Celestial Bodies, after scenes of rehearsals and discussion, we sense a pang of solemness in the performance that comes from knowing the private lives of the dancers. In other words, their realities have seeped into their art, becoming serpentine in both their flow and communication.

Dance Grozny Dance

In 2002, Dutch filmmaker Jos de Putter made The Damned and the Sacred, also known as Dans Grozny Dans, a documentary that follows a Chechen children’s dance troupe on a cross-Europe tour. Like Tankograd, the film is a testament to art as salvation. When a youthful Muslim generation must confront a life-threatening situation, they rely on a perfected and expressive tradition to guide them out of darkness. The Damned and the Sacred tackles the ferocity and precision of traditional Chechen dance amidst a landscape of Russian missiles, used to crush and dismantle terrorist attacks by Chechen rebel forces.

Following the troupe on tour in Europe, de Putter’s camera is never evasive, toggling between the bedazzled audience and the performers’ confession box. Intimate interviews with the young dancers and coach reveal a mission to show the world, through graceful steps, that Chechens are not bandits and terrorists. As their coach explains, Chechens have been taught from a young age that they must be controlled by an imperial European power.

Nowadays, control does not offer a solution or an escape when people are sick from powerlessness. How does one gain control? Where does one feel empowered? On stage, of course, where the goal is to convince the audience that each performer has a volcano within him or her that can be controlled with mind and body. Among the dancers, some hail from refugee camps, while others are average school children; either way, like Tankograd’s dancers, their drive to dance the pain away, or at least their current reality, eclipses the stage and leaps into the camera’s eye. Both Bertram and de Putter have isolated and made beautiful the fiery spirit— the antidote, the cure—at the centre of political and historical tragedy. As a self-proclaimed non-expert in the field of dance, Bertram says his decision to make Tankograd was not to merely make a dance film, but to tell the strongest story. What interests Bertram the most about filming dance is the moment that the performance becomes an emotional thread or story unto itself. To him, dance has the potential to be a mood or metaphor that articulates the grander environment offstage or outside the studio doors.

Dance for Dance’s Sake

Other documentary films of the dance genre have steered away from the background noise and headed straight for a visual and logistical study of the art form. Fredrick Wiseman’s La Danse, for example, is an opus doc that follows the prestigious and gruellingly demanding rehearsals of the Paris Opera Ballet in the opulent Palais Garnier. Infamous for his cinematic grilling of institutional systems, Wiseman employs a similar approach in La Danse, by simply letting the camera eavesdrop on every step in the creative process of one of the most renowned ballets in the world. Wiseman’s film does not attempt to show dance as a means of coping. If the Paris Opera Ballet holds any historical reflection, it is of the stubborn ballet tradition itself and how it develops within the walls of its discipline, without trying to stretch its function beyond its place in culture.

In 2009, London-based artist Tacita Dean chronicled three days of rehearsals by the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in her film Craneway Event. The dance, which would be Cunningham’s final piece, is a site-specific performance staged at Craneway Pavilion in Richmond, California, overlooking the San Francisco Bay. Craneway Event toggles between sequences of hard-silhouetted dancers against wafts of soft window light and Cunningham’s quiet observations and direct commands to his ensemble.

Since the 1950s, filmmakers have been recording Cunningham’s work, but it was not until the ’70s that the choreographer took an interest in more experimental ways of shooting his craft. Known for his tendency in the past to direct the filmmakers who captured his choreography, Cunningham gave way to Dean’s camera in Craneway, which is very much a document of her own supervision. Shot primarily from wide angles, the film does not favour particular dances but rather observes the process of individual performers absorbed in the preparation and exploration of movement. And in both its sonic and visual tones, Craneway Event succeeds in emulating Cunningham’s penchant for open space and stillness.

Two Generations, One Story

Cutting between dismal landscapes, intimate glimpses into the private lives of the dancers, interviews with experts at the Movement for Nuclear Safety, and expressive dance sequences, Tankograd fluidly balances art and history onscreen. Two voices are heard—those of the older and younger generations, who have either witnessed a disaster or suffered their whole lives through the consequences. According to medical professionals, the health of each new generation in Chelyabinsk has deteriorated to the present point where no more healthy babies are born. Radioactivity advances deformation and cancer, while the city remains a dumping zone for nuclear waste from both Europe and North America.

Bertram says his interest in the modern dancers of Tankograd was triggered by black and white photographs his ex-girlfriend, a dancer, had taken of go-go dancers in Western Siberia. These dancers would be the focus of his film—contemporary artists by day and nightclub entertainers by night. The fact that Chelyabinsk was the birthplace of the first Soviet nuclear bomb, the base of a Soviet Union nuclear weapon program during the Cold War, and the site of the 1958 Mayak Accident where a massive nuclear reactor exploded, leaking radioactive waste into the river and soil, only made the story more complex and politically resonant.

Not just a document of dance rehearsals, Tankograd examines the psychological block of the people of Chelyabinsk, who collectively suffer from its hazards, and the coping mechanisms of the young dancers who stay afloat in the heavy atmosphere. Bertram says the story of the dance company and the city’s Cold War history belongs to one thought. “I like the idea of making films like literature, with several layers and complex stories, as in real life. You have love, dance and politics in one mix. You zoom in to where it’s very intimate and you zoom out to the macro perspective. I think that’s what creates the dynamic of the film.”

Remixing

Capturing the essence of the dance form also involves many layers and cuts that, in a sense, work to re-structure the performance, to essentially interpret another person’s choreography. A filmmaker who shoots dance must also think of himself as a choreographer because he chooses what to capture, then controls the cuts in the editing room to assemble an entirely new perspective of the initial art piece. Well-executed dance can stand alone as an emotionally charged story, thus touching upon the very psychology of film, apropos of Kuleshov, where images are cut and ordered to create a relationship among separate elements.

For Boris Bertram, learning to use the camera to coincide with a dancer’s style is key when expressing the art form. He remembers a moment while filming one of his central characters, Masha, where he literally had to dance alongside her in order to capture her improvisation. It also eases the process if the filmmaker has an open dialogue with the choreographer. During the Tankograd shoot (which took place over four years and six trips to Siberia), Bertram discussed a great deal with choreographer Olga Pona about the ideas behind each piece to further understand her vision and bring it back with him to the editing room.

Thinking rationally about the logistics of shooting 13 dancers in a studio also helps to form the sequences. Bertram’s approach was to isolate the dancers and only use two or three in a scene to gain more control over the movement. Ultimately, at such close proximity to the performance, we recognize the precision and skill of the dancer. From a seat in a theatre, modern dance can often feel distant, abstract—sometimes, frankly speaking, just plain boring.

On film, the director can literally move into the scene and create more dynamics through a variety of angles and cuts, while recording subtleties that can be lost when watching from a distance. Whereas Tankograd offers short scenes of fluent movement in close-up—sometimes captured in studio mirrors to frame both dancer and choreographer — The Damned and the Sacred lingers longer on dance performances, in both rehearsal and on stage before a large audience. Jos de Putter often encompasses the whole ensemble in wide angles, narrowing in on solos of young boys spinning, kicking, kneeling and throwing knives.

For Bertram, it makes sense to ease in and out of visceral body movements that never vary from the tone of the outside world, whereas in de Putter’s film, Chechen dance is more difficult to segue on hard cuts due to the nature of its fast pace and rigid formations where momentum is gained by the dancers as a unit. Chechen dance should be absorbed as a grand noble picture, where all elements weave together as fractals; whereas modern dance, when interpreted through a camera, can be literally walked into and stepped around, with the intent of the dance revealing itself slowly, intuitively, singularly.

Bertram’s approach to singling out dancers also lends itself to Olga Pona’s theory about the tradition of ensemble dance in Russia. Pona makes a point that Russian dancers need more ego, more self-respect, without a fear of standing out. Bertram has done a graceful job of letting specific dancers radiate on camera. As Pona sees it, the spectator should be able to sense the individual value of each dancer, as each is his own planet that influences all others, as equal personalities with mutual respect.

The Angel

One such planet in the Chelyabinsk Contemporary Dance Theatre is dancer Masha, who orbits among her peers more as an angel. Masha is battling cancer due to the radioactivity of her city, although Bertram was careful not to address this directly in the film, so as not to dampen the spirit of her work or draw too much attention to a reality she shares with so many in her city. As Masha says herself, she loves dance so much she forgets about the state of her own body. And that is exactly the idea Bertram succeeded in expressing.

Tankograd is a tribute to the passion for the art of dance, which can be found in such devastated places as Chelyabinsk or Grozny—cities that have been consumed by invasion and illness. Bertram and de Putter, in their own unique approaches, have investigated the most poetic means of body language possible and managed to identify cultural stories through the physicality of movement. Bertram recalls Plato’s words, “Dance is God’s magic to humankind;” and at the beginning of his film, de Putter shows us a tapestry that reads, “The light-footed graceful dance is a joy to himself and to others.” Both are mantras for an art that transcends its choreography and ultimately takes a new shape in the lens of a camera.