Creem: America’s Only Rock n Roll Magazine

(USA, 75 min.)

Dir. Scott Crawford

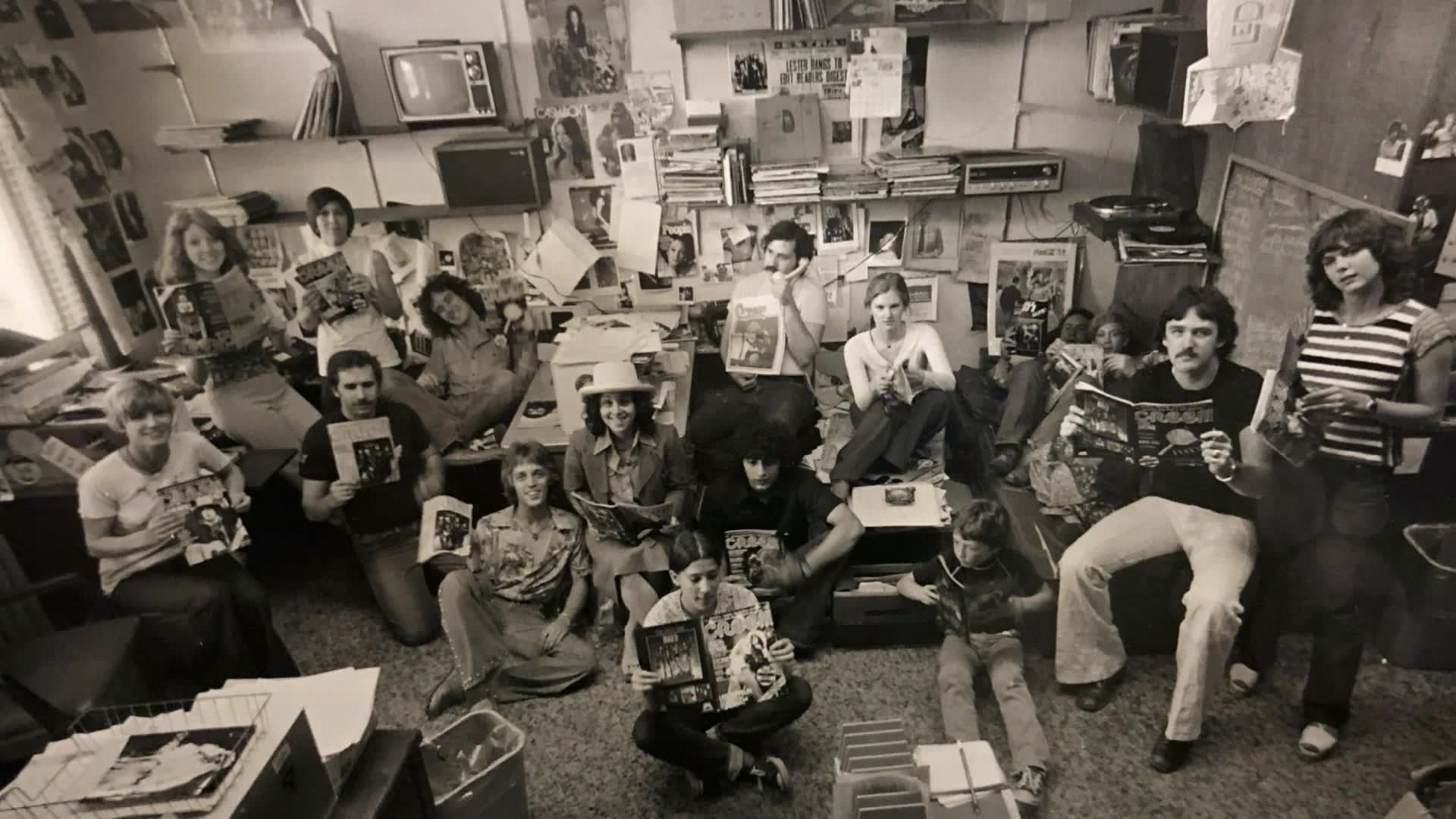

My goodness, do the offices of CREEM magazine ever look different from the creaky workspace of POV! This raucous doc from Scott Crawford whisks audiences back to the glory days of the now-defunct rock ‘n’ roll mag that inspired piss ‘n’ vinegar from music critics across the USA. The doc offers oodles of archival footage to give audiences a peek inside the dank and sketchy offices of CREEM. The liquor flowed freely while largely unqualified young folks slept on scuzzy couches, smoked reefers, hung out, and occasionally worked. Actually, the CREEM offices look a lot like the “hip” workspaces of start-ups across North America. Only now, the overqualified and under-experienced Millennials sit around on beanbag chairs while guzzling prosecco and micro-brews. At least the CREEM crew produced something beautiful—an odd word choice, perhaps, but this quasi-publisher of a boutique arts mag appreciates the energy that goes into making something that lasts.

Creem: America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine completes the circle of nostalgic Baby Boomer docs electrifying theatres lately. After celebratory portraits of Robbie Robertson, Gordon Lightfoot, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, the Canyon crew, and (groan) Linda Ronstadt, Creem offers a conversation about the artists who found their voices writing commentary about the musicians of the day. Crawford’s film recounts CREEM’s rise from its inception in 1969 by publisher Barry Kramer. The film recalls a scrappy and defiant origin story as Kramer assembled his motley crew, which included 19-year-old Dave Marsh, who rose quickly on the masthead despite being fresh out of school. Interviewees recall how CREEM gave voice to the misfits by nurturing countercultural vibes through edgy commentary and saucy designs. One interviewee likens the experience of buying CREEM to discreetly picking up a Playboy as rock and sex were equally wicked in the eyes of parents with lame musical tastes.

Audiences expecting a larger probing of the state of publishing won’t find it here, but Crawford crafts a freewheeling essay on one outlet’s role in shaping the social history of popular music. Crawford notably assembles many surviving contributors and editors from CREEM’s history, including Marsh and Connie Kramer, who ran the magazine alongside her husband and assumed the publisher role following his death. Crawford notably features many interviewees in multiple settings, demonstrating that the documentary results from extended conversations that unpacked the history of the magazine with key players, rather than merely aiming for greatest hits.

Anecdotes about CREEM’s first office in Detroit evoke nostalgia for a music scene where a generation found its voice. The doc also features a who’s who of rock ‘n’ stars, including Alice Cooper, Joan Jett, Gene Simmons, Chad Smith, and filmmaker Cameron Crowe, who immortalised CREEM’s most rambunctious voice, critic Lester Bangs, in the character played by Philip Seymour Hoffman in Almost Famous, which drew upon Crowe’s career as a rock journalist. Bangs, long dead, is the film’s implied provocateur as his spirit survives in the archival photos and memories of others. His rivalries with Marsh, Kramer, and fellow critics illustrate how writers and artists thrive through competition, challenging themselves when they see the inspired work of their peers. However, the interviewees recall how the nature of the magazine shifted with its migration away from Detroit and into the suburbs, and, eventually Los Angeles. The doc credits the magazine itself for retaining its edge, but shows how the machinery fell apart behind the scenes as CREEM struggled to gain the proper foothold between artistic integrity and commercial sustainability.

Part of the film’s charm is its frequent reference CREEM’s claim to be “America’s only rock ‘n’ roll magazine.” The slogan is a clear shot at Rolling Stone, which the interviewees say cheapened its authority as a music mag by wasting space on movies, TV, celebrity news, and (groan) politics. Dave Marsh, on the other hand, explains how CREEM confronted the politics of the day by talking about the music, and arguably shifted arts commentary from rote conversations of style and aesthetics to analysis of context and meaning. The CREEM crew laughs that the mag further flipped the bird to Rolling Stone by also stealing a name from a band—named after Cream, the favourite group of the magazine’s first editor, Tony Reah.

Especially fun are sequences that pull quotes from the CREEM archive that resurrect the voice of the magazine. Columns where contributors could cuss, ramble, and provoke reactions illustrate how the magazine “spoke” rock where other outlets used the square language of the establishment. A hilarious letter to the editor from Joan Jett, meanwhile, demonstrates how rockers gravitated towards the magazine as much as fans did. Crawford affords CREEM a sort of authority on the art form that a magazine like Cahiers du Cinema had on film: commentary drew from critics who really knew their shit, while the creators respected the words on the page—but weren’t afraid to hit back.

The fact that Rolling Stone still exists today and CREEM does not might have been topic for further examination. However, Crawford mostly keeps the conversation to the history of the mag itself. The doc nevertheless invites a conversation about the role of alternative publications as mainstream media either closes or sells out to the establishment—a fact that admittedly comes into play with CREEM’s demise—but the film overlooks how the spirit of CREEM endures in zines and blogs around the world. Readers and publishers of today can’t change the past, but they can look for echoes of CREEM in outlets that deserve a bigger platform. This rebellious spirit didn’t disappear. It just migrated online.

Creem: America’s Only Rock ‘N’ Roll Magazine is now streaming in select cinemas and virtual cinemas