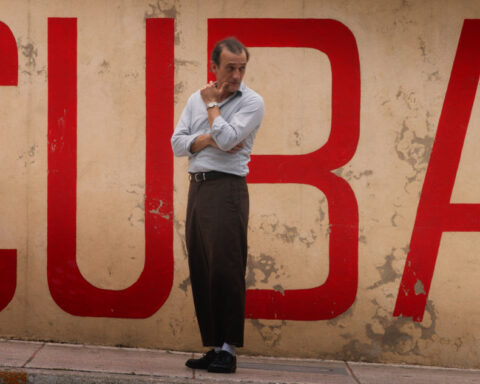

Art and culture invite individuals to think outside the boxes that limit our imaginative lives. One can thrive on the margins and occupy the space in between conventions and forms. Active engagement with art takes us to better places and there’s no better example of this than in the new Abbas Kiarostami retrospective The Winds Will Carry Us at TIFF Lightbox, co-presented by TIFF and the Aga Khan Museum. The Kiarostami showcase features several titles that illuminate the fluidity of hybrid filmmaking and the wonders of innovation that arise when a filmmaker defies categories.

Kiarostami’s films draw upon elements of documentary, neo-realism, and dramatic filmmaking, but the fine line between the forms is often imperceptible. (Except when the director uses it to smack the audience in the face, which most often happens at the end of his films.) TIFF Cinematheque senior programmer James Quandt suggests in his essay on the retrospective that the work of Abbas Kiarostami embodies the form of “Persian meta” by straddling the worlds of fiction and non-fiction. This approach more broadly situates the films of Kiarostami in the elusive realm of hybrid docs—that poetic branch of documentary filmmaking in which form itself is under inquiry. Every peculiar turn in the oeuvre of Kiarostami forces the viewer to adopt a philosophical inquiry: Is what one sees onscreen fact or fiction? Is the delivery drama or documentary? Where does one end form and the other begin?

In her essay “Hybrid Film” in Issue #100 of POV, Zoë Robertson defines this approach to documentary, saying, “Hybrid film draws on the stylistic and narrative traditions of both documentary and fiction film to varying degrees, at one time distancing its audience from objective truth while illuminating a kind of concentrated reality. It is problematic in that, by incorporating traditional elements of narrative fiction film—staging, framing, and even scripting—it shakes our understanding of truth and objectivity that the documentary genre generally strives to preserve.” A hybrid film (to borrow some examples from Robertson’s article) can be anything from Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing, which arrives at truth through performance, or an outright scripted drama like Richard Linklater’s Boyhood, which finds an element of documentary by capturing the twelve-year aging process of actors Ellar Coltrane, Patricia Arquette, and Ethan Hawke. As with the films of Oppenheimer and Linklater, Kiarostami knows that the true poetry of his films lives in their form.

Take, for example, two of his “road movies” screening at the retrospective. Taste of Cherry (1997) and Ten (2000) both employ the similar ruse of crafting a drama around the purportedly “authentic” conversations between the films’ protagonist and the random passengers who enter their cars. Taste of Cherry, which won the Palme d’Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival, features a man, Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), who drives aimlessly in search of someone to bury him underneath a cherry tree following his suicide. The film poetically meditates upon a person’s right to life—or death—as Kiarostami invites non-professional actors, often people playing something akin to their real selves, to hop in the car and chat philosophically with Badii.

Similarly, Ten sees a woman (Mania Akbari) drive around town talking with a cast of characters, such as her son, a woman en route to prayer, and a prostitute, who collectively give voice to Iran’s women by sharing their stories or actively listening to others. In the case of her son—an exasperating presence—the film uses his language and sense of entitlement to reveal how much society embeds patriarchal ideologies into boys at an early age. The son speaks candidly to his mother while frequently acknowledging the camera either with distracted glances or through explicit concerns that his mother changes her behaviour when the camera appears. Even if the mother plays a role, the young child speaks volumes with his outbursts and responses.

The more artfully composed Taste of Cherry features superb cinematography and an evocative use of its settings as Badii traverses the countryside and explores his final resting place. However, the aesthetic of both Taste of Cherry and, especially Ten suggest a direct resemblance to documentary—particularly cinema verité—through the deliberately limited coverage of the conversations that form their core. Kiarostami composes the films almost entirely from a plain exchange of shot/reverse shot angles from the driver’s seat and the passenger’s side. Save for a few obligatory pans around the countryside, which also figure prominently in his looser hybrid film The Wind Will Carry Us (1997), the films are almost unbearably claustrophobic. These conversations are long and talky with few breaks to let the viewer breathe. Ten, shot in no-frills digital, features especially protracted stretches of dialogue that border upon insufferable as the driver interviews her subjects. One remains aware of the formal element at play in which the director forces the conversations to create these character studies, but the largely unscripted dialogue—Kiarostami frequently creates loose scenarios for his films—lend a grain of documentary truth through their natural dialogue.

Taste of Cherry and Ten resemble contemporary reality television, like Cash Cab or Carpool Karaoke, with their improvised conversations mediated by the presence of the camera. The films are obvious precursors to Jonathan Glazer’s 2013 drama Under the Skin, which famously sees Scarlett Johansson’s man-eating alien drive around Scotland picking up unsuspecting random men and engaging them in conversations. The candid nature of the dialogue benefits the unprofessional actors in Kiarostami’s films and, much like it does it Under the Skin, the element of reality adds a subversive element to the exchanges. The conversations in the two Kiarostami films encourage a sense of discomfort, which puts the viewer as a third party in the conversation, like a witness left to offer the answer to an open question.

Taste of Cherry and Ten are most profoundly engaging when they draw attention to their construction, which unfolds in the gray area between fiction and non-fiction. Taste of Cherry most provocatively—and, one could say, defiantly—plays with hybridity in its famously self-reflexive finale (or cop-out of an ending, depending upon whom one asks) in which the film cuts from the handsome film stock to low-res behind the scenes footage as the director and his crew shoot the film’s final scene. This move away from the drama (intentional or by happy coincidence) suggests that the choice between life and death is to be preserved and respected. Ultimately, the film resists judgement and instead opens the audience’s mind to contemplation about philosophical and moral issues.

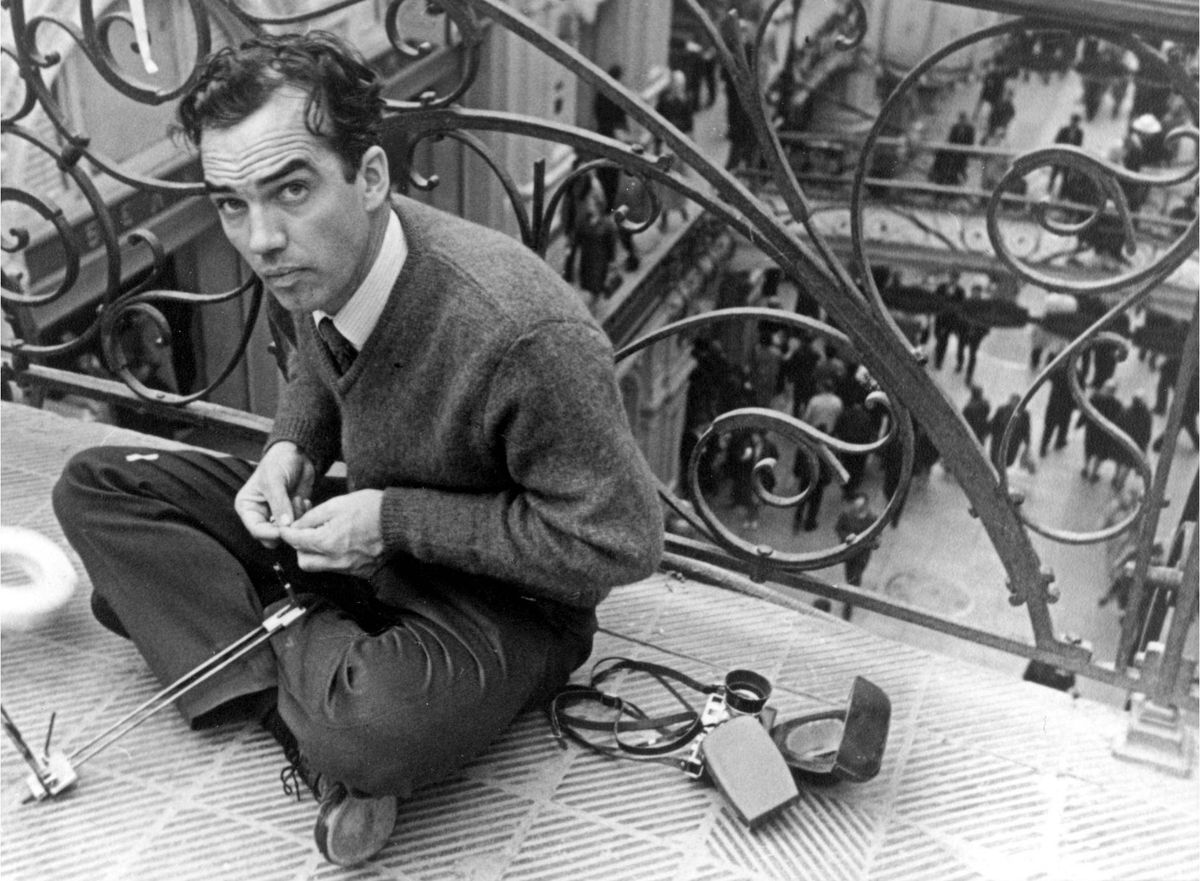

The must-see of these films is Close-Up (1990), arguably Kiarostami’s most playful and audacious experiment with form and meaning. Close-Up innovatively shows that truth can be stranger than fiction as Kiarostami takes a story that he discovered in the news and makes it into a movie.

The subject suits cinema perfectly since it considers a man named Hossain Sabzian who posed as Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf and exploited the filmmaker’s image and personality to gain access to the home of the well-to-do Ahankhah family. The conceit, however, is in the film’s ingenious casting: the director hires not actors, but the subjects of the story themselves to re-enact the drama that put them in the headlines. What ensues is in many ways a dramatized documentary, or a verité-style film made entirely with reshoots.

The approach to Close-Up challenges notions of form and filmmaking, for the players, story, and, presumably, the key facts jive with the events as they happened. The film suggests that non-fiction filmmaking doesn’t need to be in the present tense to be authentic. Something like the truth makes its way to the screen in Close-Up in this ingenious experiment in reality-based filmmaking.

The film’s observational style blurs doc and drama imperceptibly as Kiarostami retells the story from its beginning as one watches a reporter visit the scene of Sabzian’s arrest. In a bold move that rejects the immediacy of documentary—a more conventional film might show the arrest at the outset—the film contemplates the dramatic elements of space and time with one lengthy and playful shot. As a taxi driver waits for the journalist, he kicks a can of spray paint, which rolls down the street. The coverage and continuity indicates that this scene is, on some level, staged.

What follows resembles a more tangible documentary—but not really—as Close-Up shows Kiarostami going through the process of gaining access to Sabzian’s trial. He attends the proceedings, but his camera hardly plays the role of an observer during the testimony and questioning. As Kiarostami films Sabzian listening to his charges, he becomes an active player in the trial, like a third party or mediator. The film notably sees Sabzian speak more comfortably and openly to the director than to the judge. Sabzian, aware of the presence of the camera and of the opportunity to star in his own film, adopts a performative manner and ultimately defends himself by playing the part of a misunderstood victim.

Close Up intersperses re-enactments throughout the film to contextualize both Sabzian’s performance and those of the Ahankhahs as he invites them to relate their story for the camera. As the players convincingly adopt their roles and assume a game of art imitating life, Close-Up intoxicates the participants with the aura of the camera. As everyone colludes in Kiarostami’s cinematic hoodwink, the film lets the viewer appreciate film’s ability to manipulate a person with the allure of stardom, for even the Ahankhahs seem keen on lending their talents to a movie, just as much as Sabzian reaches for the perceived benefits of celebrity by stealing Makhmalbaf’s identity.

Other moments, such as the appearance of Makhmalbaf as he meets Sabzian, have an air of espionage while they signal the unscripted nature of documentary filmmaking. For example, Makhmalbaf misses his mark while parking his motorcycle and then the mic drops during the scene while Kiarostami and company fret that they have only one take to get this shot. For a film shot almost entirely with scenes composed of “second takes,” Close-Up challenges the audience to question the authenticity of images even when they seem most perceptibly real.

The hybrid films of Abbas Kiarostami reject categories and find life in the malleability of their forms and subjects. By creating a new space in which to play, they open the boundaries of cinematic freedom and draw the viewer into a conversation that lingers long after the films inevitably cut to black. Kiarostami, filming outside the box, dissolves the borders of cinema and lets them flutter in the wind.

The Winds Will Carry Us: The Films of Abbas Kiarostami is a co-presentation between TIFF and The Aga Khan Museum.

It screens at TIFF Lightbox Feb. 25 – Apr. 3.

Close-Up screens March 1 with an introduction by film scholar Kaveh Askari, while Taste of Cherry screens March 11 and Ten on March 18.

Please visit tiff.net for more information.

In conjunction with the retrospective, Aga Khan Museum offers the exhibition Seeing Beyond the Visible: The Films of Abbas Kiarostami, which runs until March 27.