“WE NEED TO UNDERSTAND THE DARKNESS. ESPECIALLY WHEN WE FACE THE LIGHT. IF WE TURNAROUND, THERE IS ONLY DARKNESS.”— Anonymous female voice

Delivered sombrely, the opening quote of Velcrow Ripper’s new feature documentary ScaredSacred, sets up beautifully the overriding theme of the film: to move ‘towards’ the darkness rather than running away. Just as effectively, it nails down the underlying metaphor, with ‘scared’ being shrouded in darkness, and ‘sacred’ illuminating a possible pathway out. The subtext is implicit—humanity will not evolve by turning away; only by coming to terms with the depths of darkness can the potential exist to evolve to the ‘light’, a spiritual place of enlightenment and hope.

ScaredSacred takes viewers on a unique pilgrimage, seen through the lens of its maker, who starts the film off lightly then builds to more disturbing scenes before culminating in a cathartic denouement. There have been numerous docs about poisonous gas leaks, bombs dropping, wars, human loss and monumental suffering, in places like Bhopal, Hiroshima, Cambodia, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Israel and New York; but Ripper brings the tragedies of all these places together in one film. It’s this collective approach that offers viewers a fresh perspective, one of hope, which is the film’s great strength.

Ripper has documented his pilgrimage to dark, ‘ground zeros’ of the world by weaving provocative first-person journal entries into a penetrating cinematic rendering of light and goodness emerging from the omnipresent brown clouds hanging over these places of human disenchantment. His resulting planetary travelogue is stunning, affirmed by a Special Jury Prize from the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), an Audience Prize at the Vancouver Film Festival and inclusion on TIFF’s 2004 list of Canada’s Top Ten films.

The idea for ScaredSacred didn’t suddenly emerge in Ripper’s consciousness. It started fabricating in his subconscious from the age of nine, when young (Steven) Ripper was taken by his parents on a pilgrimage to Israel, the Holy Land, to study the Bahá‘í faith. The Faith of Bahá‘u’lláh calls for the transforming of human life and society. It addresses both the individual’s search for spiritual understanding and the human race’s need of unity, direction and hope. Unlike the typical darkness of most cathedrals, Bahá‘u’lláh uses ‘light’ as a reality and metaphor of spiritual illumination, with the Shrines being well lit by windows and lamps. Bahá‘í pilgrimages, like those of all major religions, are meant to evoke in the pilgrim a spiritual response. When he went to Israel as a boy, Ripper still had complete faith in the universe, and he remembers being deeply moved by his experience there.

Fast forward to the mid-80s. Ripper, a young Montreal Goth enrolled in film studies at Concordia, attends a Rainbow Gathering, an annual event hosted by the Rainbow Family of Living Light, who offer attendees a set of rituals to help them reach a state of social consciousness. This one, held in Michigan, has Ripper meeting folks named Feather, Flower and Rainbow. His surname was a keeper with this crowd, but his given name didn’t cut it with them. So he dropped ‘Steve,’ adopted ‘Velcro’ and added the ‘w’ to honor his nickname, ‘Crow.’

Flash forward ten years. Ripper is deep in the forests of British Columbia, his camera trained on loggers and environmentalists for Bones of the Forest, a feature length study of the B.C. logging industry, which garners him and his sometime collaborator, Heather Frise, a 1995 Genie award. The filmmakers employ an arresting alternative experimental approach that heightens the film’s moral and spiritual message. Jim Gillespie is a 75 year-old logger-turned-environmental-activist who opens the film by pondering the absurdity of receiving just one hour of wages for taking down a fifteen-foot wide tree that would have taken two thousand years to grow. Bones of the Forest concludes with this thought—trees and the planet are no different in consideration than people and humanity. “All of creation is sacred.”

The final word uttered in Bones of the Forest, ‘sacred,’ and the same word with two letters inverted, ‘scared’, began to play on Ripper’s mind. The collision of scared and sacred propelled him to mount a “New Age preacher” performance piece in the Vancouver art-world, and then a website that he created during a residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts. Finally, after decades of spiritual contemplation, and five solid years of conceptual consideration, the appropriate film approach formed in Ripper’s mind and he set off to make ScaredSacred.

Ripper started shooting in 1999, on the eve of the millennium, with a digital camera. Carrying out his filming mission for roughly four years, he visited thirty ‘ground zeros’, of which nine made it into the film.

Rhythmic world-beat music mixes with the filmmaker’s steady voice, guiding the viewer to Bhopal, India, the site of the world’s largest industrial disaster. Eight thousand people were killed on December 3, 1984 when the Union Carbide pesticide factory leaked gases into a sleeping community, and thousands more have subsequently perished. A survivor recalls a fruit tree outside her window turning completely black on the night of the accident. But from these black ashes and yellow clouds of poisonous smoke, the collective spirit of the people emerged, asserting their power, to set up a free clinic where they could treat victims of chemical exposure. The clinic workers believe that “There is possibility if there is compassion.” The tragedy of Bhopal gave rise to tremendous compassion, and the ‘sacred’ emerged from the lost lives, lost livelihoods and lost souls who needed to reinvent their purpose in order to keep living.

Fifty-five years after the first atomic bomb was dropped on the people of Hiroshima, Ripper shows up to witness the anniversary ritual of a generation who, silenced by shame, can now tell their stories and express their sorrow publicly. It is astounding that studious attempts have never been carried out to confirm the human loss in Hiroshima. A single grave marker in one park claims the burned remains of some 10,000 unidentified victims. Many estimates indicate that roughly 80,000 people were killed instantaneously, and modest calculations declare at least 60,000 more lives were lost to burns, radiation and other after-effects.

A surviving woman recalls that while the city was burning black and red, and people were calling out for water as they were dying, she was a scared little girl who tried to bring water to the helpless, only to watch them perish before her eyes. Now she sets lanterns of light afloat on the Otagawa River. The water that could not save people then, the water that swept dead bodies away that day, is now the ceremonial water of remembrance, where lighted paper lanterns, bobbing in the night breeze, express the ‘sacred’ that has emerged from this atomic graveyard.

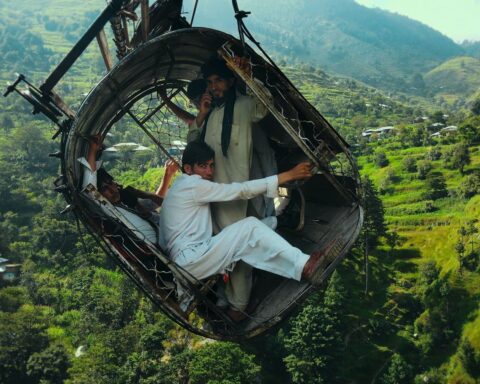

The Revolutionary Afghanistan Woman’s Association (RAWA), an outspoken force against the Taliban, takes to the streets in Pakistan to protest the fundamentalists who have been responsible for enormous amounts of violence against innocent people. RAWA regularly organizes these political demonstrations despite the great risk involved.

In Afghanistan it would be far too dangerous for them to carry out their mission; the idea of a publicly outspoken women’s only organization is a concept beyond comprehension in the conservative climate of their country. RAWA members work underground to educate girls, and to cultivate an environment where four million Afghani refugees around the world, and another million in their country can reclaim their lives. Although these women have organized to seize their power, they are in hiding and won’t be completely happy until the day they can be free in their own country.

While Ripper was overseas filming the war torn Middle East, he began to feel alone and unsafe in such a volatile environment. That’s when he got a call from home. North America had experienced its own devastating ground zero.

Arriving in New York, Ripper becomes one of many ‘tourists’ showing up in droves, needing to be close to this place of great suffering, and trying to steady their own fears of vulnerability. Filming in New York, Ripper starts to bring all the sequences of the movie closer to home. No longer an ‘over-there’ problem, he has the chance to look at the senseless and sudden loss of thousands of lives in our own yard, and to respond accordingly. How will the privileged West respond to the thousands of lives that were suddenly taken away and the burned ashes left behind where there once were towers of affluence and power?

Ripper captures the vulnerable veneer of the masses breaking down as he prowls the streets with his camera, visiting Washington Square, where mourners silently hold candle vigils and angered men debate the impossible, trying to understand what has happened and why. Emotions are raw, wounds fresh, and shock abounds that the attack happened on American soil. It’s clear that any hope to escape from the troubles of the world no longer exist: the troubles are right here and the time has come to face them.

Halloween falls seven weeks after the 9/11 attack. Ripper sticks around to capture the colourful throngs of New Yorkers celebrating, and he finds the ‘sacred’ when he becomes an ‘angel-hunter’ chasing after flashes of luminous wings. On the heels of a devastating tragedy, of monumental loss, New Yorkers are outdoors, dressed as angels—the motif serving as a visual reminder not to retaliate with mean-spirited hatred and revenge, but to respond with kindness and love.

This section mirrors a powerful moment from another remarkable feature doc, The Times of Harvey Milk. After openly gay San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and gay-rights supporter Mayor George Moscone are gunned down by an off-balance, homophobic City Supervisor, thousands of San Franciscans take to the streets with candles. It is hard to assimilate acts of violence, but from them, what we are able to evaluate is our method of response.

The evolved ‘sacred’ pathway to light that Ripper alludes to in his film’s opening is further seeded in New York, in the aftermath of 9/11. Unlike President Bush’s threats that he is “going to hunt the terrorists down,” ordinary citizens respond in kind by fluttering through the streets with feathered wings on their back. It’s a beautiful sight, gorgeously rendered by Velcrow’s camera, an extension of his discerning eye, and of a worldly soul.

Sensei Enkyo, a New York Zen teacher, eloquently summarizes the feelings being expressed by the ‘Angels’ of New York. “If ordinary people can see their own suffering and feel their own vulnerability, then they can begin to feel the vulnerability and suffering of others.” Her theory is further confirmed by an ancient Tonglen meditation mantra Ripper uses throughout the film—to “breath in suffering, and breath out compassion.” Tonglen meditation imagines that all forms of suffering, causes of suffering and bad karma gets drawn into oneself with the inhalation of breath, in the form of black rays. The exhalation of the breathgoes out in the form of white light rays, to touch all beings, and offer them temporary happiness.

From here the film intensifies, taking viewers to the depths of dark ‘scared’ places and some of the worst human atrocities, situations that one must come to understand, as stated in the film’s hypothesis, as the necessary prelude to evolving towards the ‘sacred.’

Ripper sets off overseas once again, landing in Kabul, Afghanistan, where bombs are dropping on buildings that have already been bombed, time and time again. He finds children running around in the bombed out rubble of a former cinema theatre, using the shattered brick as their playground, sporting toy guns, with old crumpled strips of movie film fluttering around them. Ripper’s narration guides viewers all the way through the film, blending his personal journey with documentary discoveries, and at this junction, the personal and the documented start to blend seamlessly. Ripper has us consider that films could be shown here if one wanted, except that there are no projectors and no projectionists and no audiences.

Contemplating the absence of ‘their’ cinema, while experiencing the privilege of ‘ours,’ we’re shown shots of young boys, holding discarded filmstrips in hand,playing inside a bombed out warehouse rather than an outdoor field of sand or grass. It makes you realize in a flash whois most affected by war. It’s bad enough that there are dead soldiers, and civilians, resulting in plenty of lost lives to mourn, but what about the ‘living’ children who are thought to be doing OK because they’re alive? You have to ask yourself if this is any way for children to grow up. Is this wasteland of war what young eyes should be seeing daily? Should children be deprived of movies and the availability of playing in fields? What will the generation of war children grow up to be? The thought of how many nurturing things they’re lacking is scary. This one section of Ripper’s film sends a louder anti-war/anti-Bush message than the entirety of Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11.

Having touched upon the absence of arts and culture in the midst of war, Ripper finds Sarwar Jan, a Sufi musician who recounts going to great lengths to keep his lute safe when he was forced to flee Afghanistan. Before fleeing into hiding in Pakistan, and leaving all his worldly possessions behind, Jan hurriedly wrapped his beloved lute and buried it in the ground. When he returned after four years in exile he was able to retrieve it, in good condition. It is not lost on the audience that the ‘lute’ and ‘loot’ sound the same. That the burying of ‘loot’ in the ground is commonly associated with criminal activity, while the burying of the ‘lute,’ a sacred musical instrument, is an act against the criminal. The safe recovery of Jan’s lute from the ground holds meaning that is far beyond any form of monetary value.

The concepts introduced in Ripper’s efficacious opening are further confirmed by Rabbi David Zeller, a pioneer in Jewish spirituality and psychology. He says,“There is a teaching that sees a person or people going to a dark place, seen as a preliminary fall for a subsequent, much higher rising than you were at before you fell. Not by seeking out suffering, or making others suffer, but in there cognition that it takes a system breaking down for something totally new to breakthrough. It’s like dancing backwards.”

In the final segment of the film we meet three parents who have lost their children to war. An Israeli father’s daughter was bombed on a bus, a Palestinian couple witnessed their daughter being shot in front of them, and a mother lost her peace loving military son to a Palestinian sniper. These parents have all had to grapple with the most difficult of losses, in the most tragic of circumstances, and despite their heartbreak, they have had to carry on with their lives.

They have all joined a remarkable group of people called the Bereaved Family Circle, inclusive of Palestinians and Israelis. It has allowed each of them to transform their personal loss to a ‘sacred’ inspired place of hope where they can reach out to others who are grieving loved ones. They have miraculously replaced negative thoughts of revenge with a desire to help others, and moved beyond their cultural differences to consolidate human similarities, expressed through the common gift of compassion.

These are all unforgettable stories of survival and resilience, and they act to inspire. Ripper continues to develop skills, seeking out engaging characters who are comfortable opening up to him. He has invested the kind of time that is necessary for finding moving stories, and he’s constructed a convincing personal narrative.

As his epic film journey concludes, Ripper is struck with a lasting realization: there is one thing that people cannot lose, and it’s the freedom to choose how they respond to whatever comes their way. Most of what lands on our doorstep will likely be beyond our control, and it becomes increasingly important to make conscious decisions about what to do with such uncertainty. When we inject positive energy into situations, we hold them in a sacred place, and when we invest in worry, we allow ourselves to remain scared. We are scared when we resist transition, and transitions are sacred when we enter them. Being scared closes you off, and being sacred opens you to possibility.

Bones of the Forest is about the planet while ScaredSacred is about humanity. They both address the spirit. The next topic Ripper wants to take on is the conscious evolution of humanity, tentatively titled Evolve or Dissolve; it will be about the necessary leap of consciousness we need to make in our relationships to each other and the planet. It is about mankind finding a place of hopefulness.

When Ripper interviewed Professor Cornell West, he asked the eminent cultural theorist to define the difference between hope and optimism. West replied that “Optimism is based on a notion of there being enough evidence to say that things look pretty good and are going to look better; it is rational. Hope considers the evidence and although it doesn’t look good, goes beyond what’s there, and takes a ‘leap of faith’ to create new possibilities.”

Hope is found within the sacred, and from the sacred hope evolves. Gathering stories from ‘ground zeros’ doesn’t sound like an uplifting way for a filmmaker to spend his time, but in this case it has paid off with a renewed sense of optimism. ScaredSacred is a masterful illustration of Ripper’s hypothesis that spirituality can rise from the ashes of world destruction.