Like many Indigenous people, the distinguished Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin grew up in a society that was taught to hate her and people who looked like her. When she was younger, she realized that was something she wanted to change. “I think I was 12 years old when I decided that. I was fighting against the educational system that for so many generations taught children to hate us. It’s as simple as that,” explained Obomsawin. “For many generations, those [school] books taught the history of our country, and the basic reason was to take [it from us] and to make sure that people would dislike us and hate us.”

As a young adult, she went on to speak with children in classroom settings about the true history of Indigenous people across Canada. “First, I was working with scouts. After that, I started going into classrooms. I got lots of invitations. I was a part of many tours across the country that included residential schools at that time,” she said. It was through this advocacy work that she was first exposed to the power of filmmaking.

In the ’60s, she appeared on the primetime CBC documentary series Telescope. “I was doing a campaign to build a swimming pool in my community because our children were not welcome in the next-door community. That became a very difficult thing to do, when I thought it would be easy,” she explained. “From there, the [National] Film Board, producers and directors saw it and invited me to talk to them like I did in the classrooms. I learned and I realized how powerful film is. And this is why I’ve remained here all these years.”

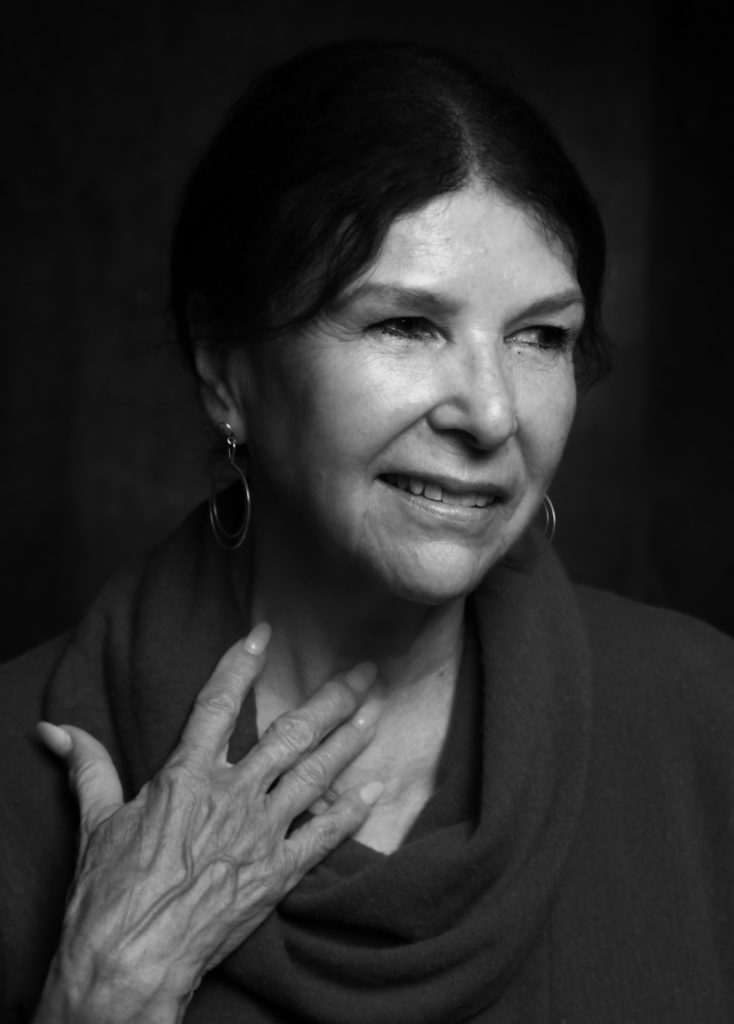

Last year, Obomsawin was honoured and celebrated at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). During the TIFF Tribute Awards ceremony, she received the Jeff Skoll Award in Impact Media for her work in highlighting and raising awareness of Indigenous issues through documentary filmmaking. Many of her films covered historical events that caught the public eye not only in the Canadian media landscape but on an international level as well. Most importantly they were told through an Indigenous lens. A special screening programme, “Celebrating Alanis,” was also dedicated to some of the landmark works she directed. Over the past five decades, Obomsawin has directed 54 documentary films—the vast majority for the NFB—chronicling the struggles of Indigenous people, yet also showcasing their resilience and strength. Looking back at some her films shows how politically resolute and courageous she has been as a filmmaker.

Incident at Restigouche , Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

One of her first prominent works, the groundbreaking Incident at Restigouche (1984), documented the police raids on Mi’kmaq fishermen, carried in order to impose new government restrictions on their fishing practices. This was the film that won her more autonomy in her filmmaking decisions at the NFB. At first, the Film Board was more controlling over who she would interview, even requiring her to only interview Indigenous subjects, not white ones. After interviewing Minister of Fisheries Lucien Lessard, the man who ordered the raids and who was not Indigenous, she stood her ground. She secured the right to finish the film with little interference from the NFB.

Perhaps her most notable film is Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), which covered the historic confrontation between Kanien’kehá:ka land defenders, Quebec police, and the Canadian army. This was also known as the Oka Crisis. Obomsawin spent 78 days filming the standoff that started off as a barricade and turned into an armed confrontation bringing international attention to Canada’s treatment of Indigenous people. The film itself made history by becoming the first documentary to win the Best Canadian Feature award at TIFF (then called the Festival of Festivals).

In Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger (2019) Obomsawin profiled the short life of young Jordan and his medical needs, which initiated a political battle over equitable access to health, social, and educational services for Indigenous children. This struggle resulted in Jordan’s Principle, a legal ruling which states that Indigenous children must have access to all public services when they need them and that those services must be paid for by the first-contacted government agency, with payment jurisdiction being worked out later. As an Indigenous person myself, it was hard for me to watch Indigenous children be treated with such callousness over money, which just happens to be another extension of Indigenous genocide. In the film, lawyer Julian Falconer sums up the situation quite honestly by saying, “we perpetuated the oppression, we are the beneficiaries of colonialism, we are racists.”

Obomsawin again proves the power of documentary filmmaking in her recent short film Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair, which made its debut at TIFF this year. In the film, we see Sinclair give a stirring speech about the effects that residential schools had on the hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children who attended them. Obomsawin interweaves footage of past testimony from survivors, creating an impactful and at times tearful narrative. “I would tell you that every word he said was important. It’s hard to part with any of the words. He is such an important person in our lives. You learn so much history just by watching this film. Every word teaches you something. It’s incredible,” said Obomsawin about Sinclair’s speech. “To see all of those people who are part of it, who have gone through that terrible experience of the residential schools. It’s so sad, but it’s also very beautiful to hear directly how they feel and what they went through.”

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Since making that fateful decision at the age of 12, Obomsawin has made a profound impact on the Canadian media landscape. She has inspired a new generation of Indigenous filmmakers to carry on the work she started into the future. Most recently, some of her recordings were used in the short film Mary Two-Axe Earley: I Am Indian Again (2021) to tell the significant story of the Kanien’kehá:ka activist who challenged the sex discrimination law that stripped Indigenous women of their “status” if they married a non-Indigenous man. Jeff Barnaby was strongly influenced by Incident at Restigouche for his 2019 zombie flick Blood Quantum. Some of the imagery in the film also resembles the faceoffs seen in Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance. “That’s just an explicit metaphor right there,” Barnaby says. “It’s taking the behaviour that you saw during that time in Canada’s history and calling it out as the kind of behaviour you would expect from a mindless zombie that doesn’t do anything but consume everything in front of it.”

Most importantly, she has cultivated a legacy of responsible representation of the communities and people she documents. One Anishinaabe teaching about “teacher and learner relationships” is that the learner must take life-long responsibility for carrying the knowledge they gain and use it for good. One major piece of advice she leaves for new filmmakers is to listen. “You just have to sit and listen to the people. This person is their story and will tell you what the story is,” Obomsawin has said. “So, it means you have to love what you do. You have to be patient and you have to respect who you’re working with. Give them time because time is the best present you can give to somebody who can trust you. They will tell you how they feel and what the story is.”