This article originally appear in POV issue #122 (Fall/Winter 2024). Subscribe today to read all articles in print as issues are published.

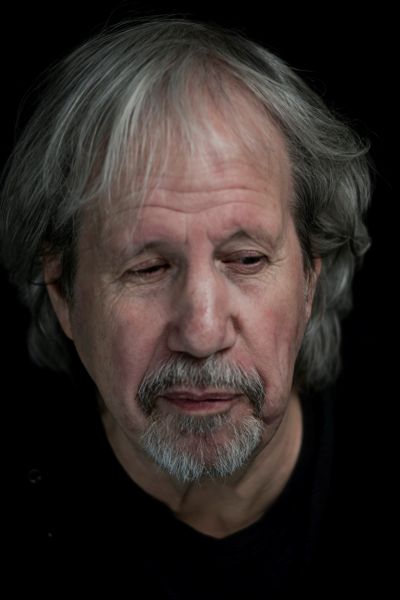

Alan Zweig has great hair. Watching his “Mirror Trilogy” (Vinyl [2000]; I, Curmudgeon [2004]; and Lovable [2007]), you can see the different eras of his hair. Short and cropped, long in the back. Side part, center part; clean shaven, goatee. His hair colour has also spanned the decades, from light brown, to mottled, to salt and pepper. Today, he sits across from me, showing a grey-to-white trajectory. He still has enough hair that he can decide where to part it.

“I have been dreaming about my film for weeks now,” he says as I’m still fiddling with the inputs and microphone placement when we met one warm July afternoon in Toronto between deluges. “It’s driving me crazy. But compared to the last couple years of doing nothing, going crazy over my film is an enjoyable place to be.”

On the wall behind him I recognize a piece of art from his documentary legacy. I ask him about it and his answer illustrates how his projects, his friends, his subjects, his research, and his epic email-writing and Facebooking overlap to create his process.

Casey McGlynn, a well-known surrealist collage artist from Toronto but now based out of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, had been in touch with Zweig, distraught by the sudden passing of his friend, the much-loved gallerist and artist Katharine Mulherin.

Zweig was beginning to work on his new film, about suicide, when he heard from McGlynn.

“I ended up interviewing Casey. I saw his art, and I asked him to make the poster for the film. And he, of course, not being a poster maker, didn’t really design a poster. He made a painting, which we cropped a little bit, and made a poster, and then I bought the original painting from him.”

The piece now hangs over his dining room table.

I’m here today to discuss his twelfth film, Love, Harold, still in rough cut during this conversation that took place in summer 2024. [The film began screening on the festival circuit in fall 2025.] It’s a film about those left behind by suicide. I was surprised to learn this is his first film with the National Film Board (NFB). A full hour would pass before we rounded the corner to that topic.

After decades working as a filmmaker, where Zweig has sat behind the camera interviewing famously grumpy people like Fran Lebowitz, Walter Rooney, and Harvey Pekar for I, Curmudgeon, and famous Jewish comedians like Marc Maron and Howie Mandel for When Jews Were Funny (2013), or followed famous complicated and multi-layered people for years, like Steve Fonyo, in Hurt (2015), and its sequel, Hope (2017), for the first time, Zweig sat behind the microphone and acted as host for Canadaland’s The Worst Podcast, which premiered in September 2024.

“It’s a celebrity show, except the host barely knows and certainly doesn’t care about what his guests have gotten up to,” said Julie Shapiro, executive producer. “[I] wouldn’t say [it’s] negative, maybe more pessimistic, or dyspeptic… that’s a word he likes a lot.”

There are a few notable things about Zweig taking on this role. For one, he calls this “a job.”

“The last time I had a job was when I drove a taxi cab. But as a filmmaker, I’ve almost never been hired,” says Zweig.

I pressed him on this question. Was it that he didn’t really want the job, or just that he hadn’t actually tried to get a job? No. He was clear. “I’ve tried to get work, but I’ve been told I don’t think you can make our show about cooking because you would bring in a mirror, start talking, and be self-indulgent.”

This time, it’s not a job he got because he’s a veteran documentary filmmaker with decades of ground-breaking films. It’s a job he got because of who he is, and what he stands for: an older man who’s not an obvious fit to speak to celebrities, who is sort of grumpy, a bit negative, and appropriately nosy. And he’s really good behind a microphone, talking to anyone, about just about anything.

How did it all begin?

“I wanted to be Ira Glass, like everybody else. But it’s an interview show, and that’s okay,” says Zweig.

Season one will have six episodes. And after its launch, Canadaland will do the internet calculus to decide if it will continue.

Is it less work, I asked? Yes, he says, but not monstrously less work. There is something different about it for him. “I’m never nervous when I interview somebody for my films; if I get nothing, that’s okay. But for the podcast, I’m always nervous, because we’ll talk for an hour, and the show will be a half an hour.”

And then there’s the delivery method that’s different. “The thing that’s interesting to me is that it didn’t even occur to me that they wanted to [air] it in the States. I just thought it would be a little Toronto show,” said Zweig. The internet, it turns out, goes everywhere.

As you watch Zweig’s film catalogue as I did in preparation for this interview, you repeatedly see him get people to open up about their darkest moments. He gets dark and he goes deep, and his interviewees follow suit. I realize this is the entire premise of the podcast, getting celebrities to open up about their worst moments.

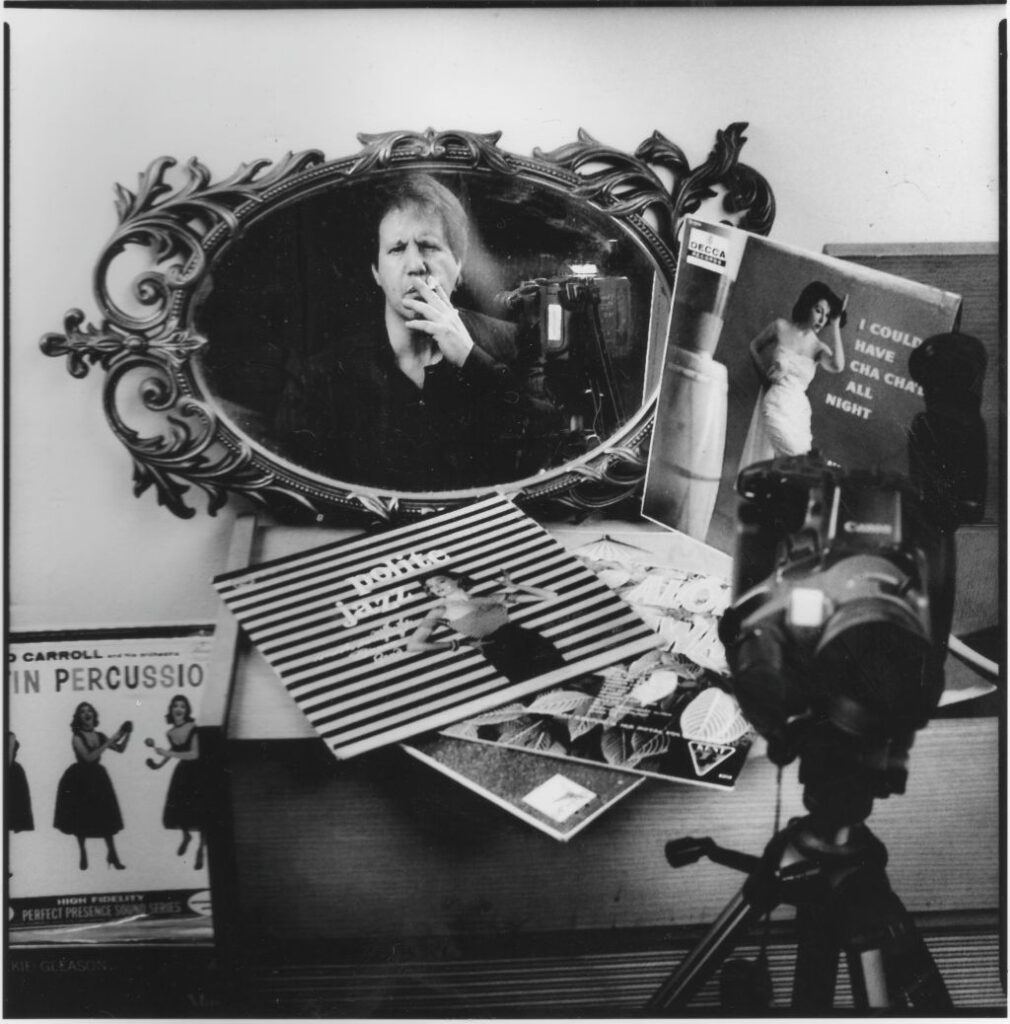

Zweig is always in his own films. His signature camera shot is him narrating his inner thoughts to a mirror. Even if he is not on-camera, he instructs his sound person to mic him so that his questions are included on the voice track of the films. This allows the viewer to ‘see’ the interaction between him and his subject.

In Hurt, we ‘see’ him as we listen to him interact with the fallen Canadian hero Steve Fonyo. Zweig prompts him to frankly break down the various chapters of his life, between addiction and homelessness, taking us through various courtrooms for domestic disturbances, to his shining moment when he ran all the way across Canada, despite having lost a leg to cancer. Zweig talks to him straight. He does not adore him, nor revel in his glory days. Instead, he reconciles the public hero with the private man, hero, and villain.

But the podcast seems to be bringing out a different side to him. Part of that is his role: Instead of being the director/producer/cinematographer, as he is with his films, for the podcast, he’s the on-air talent; the host, which the production team packages into a show. Yes, he gives notes. No, he does not edit.

It’s a show that expects Zweig to show his charming, connecting side. And connect his grumpy side to his funny side.

Kattie Laur, the Worst Podcast producer, booked the famously upbeat sports broadcaster Ron McLean to speak with Zweig. He speculates that “she thought this is the least negative person in Canada, and it’ll be funny. But I was flailing… and I’m guessing they liked that; they think the audience will enjoy hearing me flail. So if that’s true, then I think I can do this podcast. But if it’s not true, if they really think that I can make Ron McLean tell me a negative story, they’re wrong. I can’t,” admits Zweig.

This new job humanizes his flailing. But he does not fail. “I think this show is going to be very entertaining. I’m hoping that it’ll cast a wide net and it’ll resonate with lots of people,” says Shapiro.

There are crossover skills between the documentary film world and the audio world of narrative podcasts on my list of questions for Zweig. His ability to weave together an immense number of storylines into one narrative is one of them; it’s a ten-finger chord to hit in films, and he does it.

I called his ability to weave together multiple storylines his “secret sauce,” which immediately charmed him. For a moment, a gold star hung above his dining room table. In 15 Reasons to Live (2013), he wove 20 or so interview subjects on various couches, rarely identified with a name card or text, with stories that move laterally, not obviously. But still, I said, “You’re able to create a coherent storyline, even though you run through multiple characters and subjects.”

He disagreed with me and the glitter from the gold star sprinkled down to the floor. “Right. I would say it’s not,” he corrected. “It’s definitely not a coherent storyline, in the sense that it’s a story. I would say [it’s] more that you have to keep the balls in the air. You have to end in a way that makes it seem like everything that came before was leading there. It’s a bit of an illusion, but it’s a very enjoyable illusion.”

He jogged his memory of how this has played out in his various films throughout the years. The way he was able to intercut all of these different ideas, the different voices, and random conclusions, he explained, was by using the jump cut, a film technique he embraced early.

“When I made Vinyl, I worked with Chris Donaldson; it was his first film as an editor. By the time we made the third film, he was feeling his oats. Chris went on to be possibly the best editor in Canada.

“It was natural that we found this way of cross-cutting people talking. That was as much a gut feeling [as] my theory: If on the cut, you go to the next person, it doesn’t matter if he was talking about apples, and he was talking about oranges, at the moment that it switches, you’re not going ‘what?’”

Zweig went on to explain how this jump-cut approach will be different in his new NFB film: “I don’t want to put too fine a point on it, but there is grief expressed in the film, and sometimes when somebody expresses grief, I feel like the audience needs a moment. So, I can’t just cut to the next person, like I normally would have.”

As he spoke more about his film, he called it a “bad idea,” but one that he could uniquely wrestle into something. I asked him to explain further.

“People ask: What’s the film about? [I want to say] it’s about puppy dogs and rubber balls. I always almost say it apologetically: It’s about suicide. And then they get that look. I want to be conservative, but 50 percent of them, three beats later, say: ‘My uncle killed himself’ [or] ‘my brother.’ Obviously, you can’t say that suicide is common because, statistically, I guess it isn’t. But it’s common enough. Why aren’t people talking about this?”

As we talked through this layer of conversation, the tone became delicate and nuanced. He moved his hands from the table to his lap. His tone became calm. Was this the podcast host Zweig? By this point we were riffing. For ten minutes we spoke about people who had lost various family members to suicide. About different people we both know who have been lost to toxic drugs, or mental illness, and where the line gets blurry between all of these terrible things.

What happened next was a taste of what it must be like to be interviewed by Zweig. He had been watching my face as he described his film and the layers he went through while making it, and what it might uncover in others. And then he abruptly stopped. He looked up at me and said: “Now, I have to ask you, the way you’re reacting, I feel like you have a suicide story.”

Suddenly I was being interviewed. I honestly answered: “I don’t not have a suicide story, but I also don’t have one very close to me. Nothing in my immediate family or friends. But as you were speaking, I was doing the mental checklist in my mind: there’s this person, there’s that person. I don’t have to look very far.”

I took a deep breath and attempted a lane change. I wanted to talk about his interview style and technique, but to get there, I first asked how he got all these interviews for his new film. Was it a lot of research and pre-interviews? Had he chosen 20, and then funneled them down to a dozen?

No, in fact. It was none of those things. Nothing about his recent film came to him through typical research channels. They were all personal connections, or a personal connection of someone else, one way or another. And don’t even get him started on pre-interviews. That is not his thing. The Worst Podcast is designed around cold interviews.

As we did a number of times throughout our conversation, we went back to the beginning.

“When I made Vinyl, I knew nothing. And over the years, people would tell me interesting things about rules that I was breaking. But the other thing is that people would tell me what they did, and sometimes it didn’t make sense to me.”

For example, the idea of following a subject for six months to hang out with them without the camera until they’ve earned their “trust.”

“You couldn’t pay me enough. I would go out of my fucking mind,” he begins. “As soon as they’re about to say something, I tell them: Fuck yeah, shut up. Don’t tell me anything interesting when the camera’s not running. Do you have a couple hours and I will get my crew? Isn’t that cheaper than taking them out for coffee for six months?”

Zweig took a pause. If he still smoked, it was where he would have taken a long drag on his cigarette. “I love that word: [trust]. Because you don’t have their trust. I don’t care how many times you went out for coffee with them. You don’t have their trust.”

Then he draws the point closer to me.

“I don’t trust you. I’m just talking because I like talking. People will tell you things if you get out of their way. That’s all I can say. Did they trust me? No, not really. They trusted me enough to sit in front of the camera for two hours. And they talked about what they wanted to talk about, and that was good enough for my film.”

There were still my questions. Was the podcast chapter his new thing? Had he indeed pivoted? Would the podcast also keep him up at night?

“I can’t make enough just making my little films every few years,” Zweig admits.

“I don’t think [the podcast] will be a steady gig,” says Zweig. “There will be five or six episodes in season one, and they will decide if the show will continue.”

But then he followed up with a self-concluding thought, very on-brand: “I’m kind of a prima donna, in my own way, and I’ve been allowed to be one. For all I know, I’m not capable of not doing what I do.”