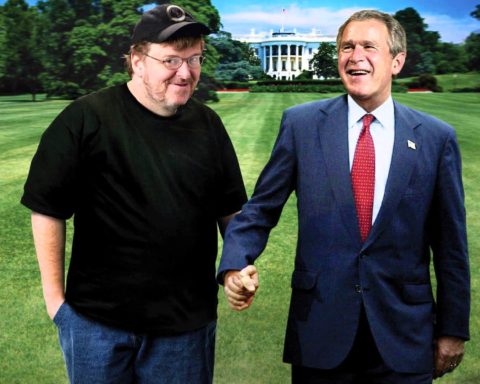

People kept asking us after seeing our exposé of Michael Moore in Manufacturing Dissent, “Are you still going to watch his films now that you’ve done this film about him and his documentary techniques?” Our reply was simple: “Of course we’re going to see them. In fact when we see Sicko we’ll have a bag of popcorn in one hand and our Ontario health cards in the other.”

We honestly thought we’d be able to watch Michael Moore’s films and still enjoy them, but we were wrong. After doing our film, we now had the key with which to follow Moore’s docs. We found ourselves analyzing Sicko and wondering what he had manipulated in each scene. We remain committed progressives nevertheless. You don’t have to believe in Michael Moore to maintain leftist ideals.

We were fascinated and horrified by the first half of Sicko when Moore talks to doctors and HMO (Health Maintenance Organization) administrators who admit that they were given financial bonuses to reject patients’ treatments and surgeries. We were equally stunned by the story of the uninsured man who accidentally cut off the ends of his two fingers and had to choose which one to reattach since he couldn’t afford to reattach both of them. One cost $60,000 and one cost $12,000 and he chose the $12,000 option.

But then Moore turns up the Hans Zimmer symphonic soundtrack and one shocking anecdote after another is shown of middle-class Americans who are denied health care. By the fourth example we were starting to feel manipulated and wonder about the truth of these stories. We can’t help it. After examining Moore’s films for over two years we know he changes things and fudges the truth for greater dramatic effect.

In Sicko we never get to hear from the insurance companies regarding any of the cases that were denied coverage. We suspect there is no excuse for the behavior of the insurance companies but we would like to have heard something from them, even a “no comment.”

The second half of the film we found more problematic. After painting a bleak one-sided portrait of the American health care industry and the callous and greedy insurance and HMO companies, Moore takes us to Canada, Britain and France, all portrayed as utopias where the health care is more or less perfect. Broadsides and broad strokes are his stock and trade, as we know.

In Canada, or at least London, Ontario, which is where Moore shot the Canadian portion of Sicko, the longest wait in the emergency ward to see a doctor is 45 minutes. This doesn’t quite jive with the five hour plus wait Debbie had with her mother at the emergency wards in both Toronto and Montreal. Long before we knew the reality first-hand, we were troubled by Denys Arcand’s remarkable Les invasions barbares, which unfortunately was both an accurate and dramatic portrayal of the extended waits and all-too- frequently substandard treatment in Quebec hospitals. This is a result of a great idea being starved of adequate funding to deliver on the promise of world-class health care for all.

Free is a word we hear a lot in Sicko from this point forward in the film. Moore uses two half-truths to convey what he sees as the whole truth. One half truth, and it is true as far as it goes, is a sequence where numerous ill-informed American right-wing pundits are seen on TV using the Canadian universal health care system as a whipping boy to spread their conservative political agenda. Then he cuts to Canada and shows a near perfect health care system. Again this is true as far as it goes but to pretend two partial truths comprise a whole is a mistake.

If Moore was interested in the reality of the Canadian health care system he could have sought information from either informed Americans or concerned Canadians. The problem is the argument is so dumbed down and black & white, that that there isn’t any analysis here. What we are led to believe is: Universal health care—good; Private, for profit, health care—bad. For those of us enjoying both the benefits and pitfalls of universal health care, the argument is not insightful and lacks subtlety.

In Britain, Moore talks to a doctor who owns a $1 million dollar home and can afford an Audi on his National Health Service salary. We can only think this was included in the film to get the support of American doctors, and their well funded lobbying interests, who are terrified that a national health system will reduce their salaries.

But do the nurses in the United Sates who are rallying around Sicko realize that the systemic changes Moore is agitating for will mean both a lower salary and higher taxes for them?

The French system comes off the best. In fact, after watching Sicko, we want to move there. The government not only covers health care, it supplies home aides to new parents to do the laundry and clean, and French patients are given free vacations to recuperate from illnesses. Where do we sign up? But we still have reservations as does France apparently. France’s last election, which brought conservative Nicolas Sarkozy to power seems to be a rebuke of some of these more generous policies which has lead to unprecedented taxes and economic stagnation, regrettably causing some of France’s best, brightest and most affluent to flee the country.

Having left France, Moore presents us with one of his silliest stunts of his career: he takes volunteer 9/11 rescue workers who can’t get affordable medical help from American health insurance companies to Cuba. Having seen American officials on TV saying that the prisoners at Guantanamo Bay are being given first-class free medical treatment, Moore goes by boat to Gitmo, brandishing a megaphone to demand free medical treatment for his fellow American heroes. We keep wondering, isn’t this the same place where prisoners are complaining about being tortured by the Americans? Moore can’t have it both ways. We get it that he’s being satirical with his interpretation that the 9/11 heroes are worse off than prisoners at Gitmo, but it’s a callous and insensitive comment.

When the siren wails outside Gitmo’s prison walls, Moore takes his rescue workers to a Cuban hospital where they welcome him with open arms. The Cuban doctor we see is grinning from ear-to-ear as if he can’t believe his luck. He’s getting free publicity for Cuba compliments of Michael Moore who has landed on his doorstep. Of course, no one is able to walk into a Cuban hospital, camera in hand, and interview doctors about the Cuban health system. All of this was set up in advance. Apparently Moore and his 9/11 workers went to a hospital for foreigners and dignitaries where patients usually pay. We’ve been to Cuba, as tourists, and in all our travels, we never saw a pharmacy as well stocked as what is shown in Sicko.

Admittedly, Sicko has kick started the universal healthcare debate in the US and Democratic candidates have jumped on the bandwagon. But the one thing that Michael Moore doesn’t stress is that the only way to get universal healthcare is through higher taxes. It’s a simple solution really, but one that isn’t discussed at all in America—the third rail of US politics—since no candidate in a tight race can afford to publicly declare their intention to raise taxes.

How are the likely nominees handling the issue? Democrat Hillary Rodham Clinton proclaims, “America is ready for universal health care,” while her rival in the party, Barack Obama agrees, promising, “Quality affordable health care for all.” Mitt Romney, representative of the Republican position, believes in tough love when it comes to “socialized” health care. He highlights this have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too stance on his campaign web site. “We can’t have as a nation 40 million people—or in my state [Utah], half a million—saying, ‘I don’t have insurance, and if I get sick, I want someone else to pay.’ It’s a conservative idea insisting that individuals have responsibility for their own health care. I think it appeals to people on both sides of the aisle: insurance for everyone without a tax increase.”

It’s not unusual for politicians to make promises and then not deliver. It may be too much to expect of filmmakers, too. We were thrilled when Moore touted Fahrenheit 9/11 as promising to get Bush out of office, just as he said that Bowling For Columbine would change the gun crazy culture in the States. Now, with Sicko, he promises to change US health care. Pardon our skepticism. The film has done astonishingly well at the box-office, but it seems unlikely that free health care will be coming to the United States any time soon.

It’s our belief that people haven’t listened to Michael Moore because he has abused the unspoken bond between documentary filmmaker and audience. Those going to a doc have a right to expect that what they’re being presented is the truth and if either then or later they discover they’ve been intentionally lied to, they have every right to turn on both film and filmmaker. American indie guru John Pierson, who marketed Roger and Me wrote an open letter to Moore in IndieWIRE: “You’re on the side of the fucking angels with Sicko and no lapses, omissions or oversimplifications can detract from its contribution to the greater good. But please baby please, let the movie, which you have so beautifully made, do the talking.” We wish it were as simple as that but we believe the root of the problem is the lapses, omissions and oversimplifications that undermine and thwart Moore’s stance. Moore is hard to ignore but easy to dismiss. Of course it’s good to raise the health care issue, forcing the debate. But what’s it all about? Is this real commitment to long-term social change or is it about selling some movie tickets this weekend? As with the other Michael Moore films, we predict it won’t change a thing in America. Universal health care will remain out of reach for the poor and downtrodden, who really do need it, unless they go to that utopian socialist country to the north, Canada. So thank you Tommy Douglas, but please America, regardless of what you do (or don’t do), we’d still like our doctors and nurses back.