Claude Lafortune was everyone’s grandfather, wrote Tanya Lapointe in Le Devoir while paying tribute to the artist earlier this year. “For nearly three decades, he was a stable and inspiring figure in the lives of many generations of children.”

Lafortune, who passed away in April at the age of 83 after contracting COVID-19, entranced children young and old with his gift for creating worlds and characters with little more than a sheet of construction paper and a pair of scissors. He is Quebec’s distinct reassuring figure like Mr. Dressup or Mr. Rogers who was the first teacher for many children as their parents plopped them in front of the television to be entertained and educated. His series Parcelles de soleil (Parcels of Sunshine) and L’Évangile en papier (The Paper Gospel) sparked children’s imaginations with deceptively simple creations that engaged with stories of faith and humanity—welcome lessons for kids to grow up with a sense of responsibility to their neighbours regardless of their religious beliefs.

The artist’s story is the subject of the documentary Lafortune en Papier – The Paper Man by Tanya Lapointe. The film marks the first solo directorial debut by Tanya Lapointe following her doc 50/50 with Laurence Trépanier and over 15 years as a journalist with Radio-Canada. The Paper Man, which premieres at the Whistler Film Festival on December 10, is a love letter to Lafortune and his timeless art. Lapointe joins Lafortune as he readies his paper creations for displays at exhibits, which bestow upon the veteran new levels of artistic recognition that he sometimes struggled to receive as a television personality. (The nature of being a children’s performer and engaging with questions of faith arguably limited appreciation for his craft in some eyes.)

At the same time, the film culminates with Lafortune receiving greater recognition within the artistic canon. Throughout their journey together, though, Lapointe and Lafortune encounter many people, now adults, who were inspired by the paper creations that fuelled their youth. Lapointe engages with both the man and his work as The Paper Man observes the exquisite details and craftsmanship behind Lafortune’s surviving body of work that endures for generations. (Many of the figures created during the series’ runs were destroyed when the shows went off the air.) The doc also finds affinity for Lafortune’s hand-crafted method of creating tactile figures in an age of avatars and computer wizardry—a point that is especially novel given Lapointe’s other body of work on Hollywood mega-projects directed by her partner Denis Villeneuve, including the Oscar-winning Blade Runner 2049 and the upcoming Dune, which credits her among its producers.

POV spoke with Lapointe by phone ahead of The Paper Man’s premiere at Whistler to discuss her experience with Claude Lafortune, bringing these childhood memories to life, and, of course, what one can learn while juggling two projects of wildly different scales.

POV: Pat Mullen

TL: Tanya Lapointe

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: Did you know Claude Lafortune before beginning the project? You seem to have quite a rapport with him in the film.

TL: I grew up watching him on television, so that was the start of the relationship, so to speak. When I became a reporter in 2000 for Radio-Canada, I interviewed him a few times. He was still able to amaze me with his paper and scissors, but nothing came of it at that time. Then in 2018, he sent me a Facebook message since he had created a profile and was connecting with fans from the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, and so on.

POV: That must have been a surprise. How did that lead to the film?

TL: He told me that he was doing an exhibit. I usually don’t invite myself to people’s houses, but I said, “I would love to see your workshop. Is this something that we can do?” He said, “Sure, come on over.” The connection was instant. We spent an hour and a half just talking away. At the end of that conversation, I asked Claude if he ever thought of opening his paper world to someone for a documentary. He said, “I’m not Céline Dion. It wouldn’t be a very glamorous documentary.” I said, “I know that’s true to you.”

POV: With your background in journalism, how is making a documentary different from pursuing a story journalistically?

TL: When you’re a reporter, especially doing television, you’re always working on a deadline. You’re always writing the story in your head as you’re doing it. Whereas with this project, I allowed myself to do a formatting process in my head and just let go to see where this journey would take us. It was a wonderful adventure in the sense that, although I knew when it started, I didn’t know when it was going to end. I was essentially digging for gold. I kept finding gold and I would follow it. There was more freedom, more adventure. I knew that I had some wonderful puzzle pieces, but I didn’t quite know how I would put them together. In that way, there was much more freedom than in the traditional journalistic format.

POV: The archival materials are such nice puzzle pieces. Were there challenges in obtaining this material after some of Claude’s figures from the show were destroyed?

TL: Claude had thankfully taped a lot of his shows. For Parcelles de soleil., and L‘Évangile en papier, we had all of those on DVD. Radio-Canada still has most of Claude’s work in their archives, so it was just a means of accessing those files and getting them transferred. For events like the fête nationale [the 1981 parade, which featured 15 paper floats created by Lafortune], we reached out to TVA, and they had kept only 10 minutes from the entire parade. It was a beta tape, so I had to buy a beta machine and transfer that into digital format. I wanted to leave no stones unturned. It was fun to find these things where Claude had left his mark in Quebec, in Canada, and the world. The bigger challenge is once you’ve assembled the movie. I have 250 archival elements that had to be cleared.

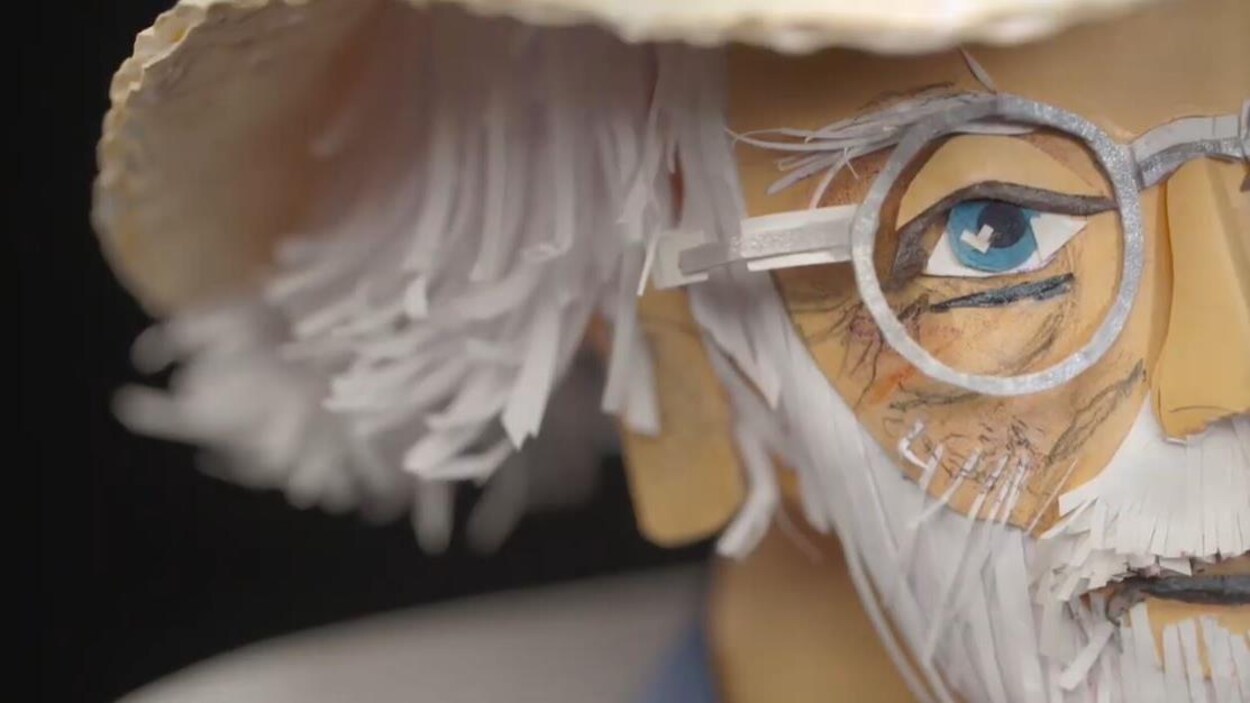

POV: What was your approach to filming the paper figures? Paper is flat but the film is quite dynamic.

TL: I filmed them in the same way that I approached filming Claude. There’s an element of nostalgia of TV from the ’70s and ’80s. I wanted people to feel like they’re in the 21st century and with someone who’s still passionate. That led to the idea of this road trip and being very dynamic with handheld [cameras] and moving around with Claude. I am fascinated with what Claude created and I wanted to create that sense of awe and wonder on screen. For me, that was being really close to the sculptures.

My DP, Hugo Duford-Proulx, and I had a dolly, so we created the sense of three dimensionality by having the camera move a little bit so you feel like you have your nose right next to the paper figures, and that you can see every little detail that goes into the work. When I was a kid, that’s how the shows were filmed: the closer you got to those paper figures, the happier you were, because you got to see all those details. That was important because Claude was a very meticulous artist and his art was become more refined over time

POV: Do you have a favourite figure of Claude’s?

TL: My favorite is probably his self-portrait because there’s a story behind it. One year in [to filming], I asked Claude, “Have you ever considered doing your own portrait?” He said that people asked him that all the time and he always said no. I said, “What if I asked?” He said he’d think about it and, two weeks later, he called me and said he made the portrait. Even though he resisted the idea of immortality, he became immortal. Despite the fact that we think that paper will be thrown away in two years and won’t be any good anymore, he’s proven the opposite: paper can outlast our expectations of it. When he passed away in April, I was obviously devastated because I was speaking to him a few times a week by that point. His self-portrait is a symbol of our collaboration because it was made specifically for the documentary.

POV: How far along in production were you when Claude passed away?

TL: It was exactly two years after we started filming that he passed away. The last shoot was a year ago with the kids in the school. At that point, Claude had some pulmonary problems, but he was getting better. I thought he’d be fine. He had such vitality. We were thinking of doing another shoot in June. The kids who had participated in the workshops were going to present their paper creations, and Claude would be there with a big reveal with his self-portrait. That was, for me, the culmination. I was hoping to interview other participants from Parcelles de soleil, and then everything just stopped. Claude wanted to see the film before he passed away, so I felt a responsibility to finish it as soon as possible. Claude brought so much light to people’s lives and I hoped the film would bring some light in these dark times.

POV: This pandemic has disproportionately affected the elderly, and we see some dismissive attitudes towards our elders with the way people talk about COVID. How did losing Claude affect how you saw the pandemic unfold?

TL: It was important that we didn’t just finish with a statement that Claude was dead. Claude was a celebration of light and art and creativity. What saddens me is that when we talk about people passing away, we’re always talking about stats: how many people have it, how many people died. There are no stories of the people who die. People sometimes say they’re tired of being in quarantine or people complain, but when someone has passed away from COVID, you realize how difficult it is for the families. The losses people are experiencing are harder. I hope that Claude can be a reminder that even though people have passed away or will pass away, we remember their stories and we keep telling their stories. When he passed away, I wrote an article in Le Devoir saying he was everyone’s grandfather. I think his loss resonated with a lot of people.

POV: In your article in Le Devoir, you noted that Claude never taught his craft to anyone. Do you worry this will be a lost art?

TL: Jérôme Cloutier, the artist who did my colour grading, watched the movie just before Halloween. He came back the next day and he showed me pictures of paper kittens and pumpkins that he had cut out with his kids and put in the window. He did that himself, like Claude taught himself. I hope that this isn’t an isolated case and that the gives people the desire to start expressing themselves creatively with papers or with any materials, really.

POV: For your previous documentary 50/50, as well as your work on the Hollywood films Blade Runner 2049 and Dune, you’ve made books to complement the films. Are there plans to do a book with Paper Man, and how do you choose to approach a work in different mediums?

TL: Later on into 2049, Dune, and even 50/50, which is an exploration of gender equality, [the books] are more my own exploration of those movies and that subject matter. But for Claude, it doesn’t feel like it’s my place to tell that story. I accompanied Claude through the documentary process and I told his story in that manner with these archive images. Visually, there’s something about these archives—how fascinating the colours, the images, and the haircuts are—that you can’t translate back to paper. It would be someone else’s project to do. For me, there’s a delight in finding new projects and new ways of expanding a film. For this film, the soundtrack by Viviane Audet, Robin-Joël Cool, and Alexis Martin will be on Spotify. The music is such a strength and accompanies our journey on screen. It’s not a book, but it’s a way of expanding the movie onto another platform.

POV: Can you tell me more about your work as a producer on Dune? On one hand, you have this small, artisanal, intimate project, and on the other, you have this epic Hollywood blockbuster with CGI and a giant world.

TL: I think the two complemented each other. Working with Claude was a very intimate and personal journey and storytelling process. It was just the DP, Claude, and me. I wanted to be a fly on the wall and I thought that was a strength for telling that story. Whereas working on Dune, obviously no one’s a fly on the wall—you have hundreds of people on set every day and the logistics are much more complicated. It’s an adrenaline rush to be on these sets, to be working with so many people, and to be resolving problems or preventing problems from arising. I think those two were perfect with each other. The truth is that my main occupation is to be a producer on Denis’ movies. We were shooting Dune in Budapest, so I would come to Montreal for 52 hours to be with Claude, and then go back to Budapest and work full time on that. There wasn’t a week that would go by where I wouldn’t be in touch with Claude.

POV: How did the projects feed off one another?

TL: I feel that I take away as much from the documentary as the large scale movies in terms of producing or directing. The two of them are about storytelling. Sometimes I’d be on set and think, I’m taking this from my experience with Claude and bringing that psychology into my work on a larger scale, and with Dune, the opposite is also true. You’re learning from different people and feeding a sort of a cross-culture production experience.

Lafortune en Papier – The Paper Man premieres at the Whistler Film Festival on December 10.