The lush, green serenity of the forest envelops Silvicola, a new documentary about people who spend their working lives amongst the trees. The film, at once stunning and sobering, taps into the paradox of being both a forest worker and a forest lover, capturing the sadness that comes with witnessing—and participating in—the over-harvesting and destruction of forests with complex ecosystems and dwindling old-growth trees.

Director Jean-Philippe Marquis knows that his feature can only capture a fragment of the complex conversation around forestry in British Columbia. But, by foregrounding the people who dwell in the day-in, day-out reality of the industry, he hopes to contribute first-hand insights. He says he set a strict rule for the film: Every person in it had to be a forestry worker.

“For an NGO spokesperson at a desk to say that there’s very little old growth left, we hear that all the time,” says Marquis from his homestead in rural B.C. “But to have a mill owner look at the camera and say that, in 10 or 20 years, all his equipment is going to be in a museum because there’s just not enough wood left to supply it—that really hits home.”

Marquis initially became acquainted with the industry working as a tree planter, first in the northern reaches of his home province of Quebec, but soon across Alberta and B.C. as well. For ten summers, he laboured under the sun and rain, churning out seedlings into the dirt, a physically intensive gig that often pays per plant. Gradually, his gears started turning and he came to an understanding of his place in the forestry industry at large. It was hard to ignore the signs around him.

“I found a huge stump that was big enough that you could park a pickup truck on it,” says Marquis. “I was having my lunch on it, and wondered, ‘Isn’t that weird that we’re allowed to cut that?’”

Often at lunchtime, he’d cross paths with other forestry workers, like loggers, and get the chance to chat about their work and hear their reflections on it. He’d ask them about the emotional journey of cutting down a big tree, and a small door of understanding would be cracked open for Marquis to peer into as they’d talk about their near-death experiences on the job.

For Silvicola, Marquis “wanted to revisit those areas with cameras instead of my shovel.” The resulting film is a very intimate sit-downwith a handful of workers who let his camera tag along as they open up candidly about the emotional weight of it all. From loggers to sawyers to tree planters, the film gathers together the whole web of workers that make up the forest industry. Marquis stresses that the level of access and honesty he was able to tap into would not have been possible had he not done his own time in the forest, making connections along the way.

Trees themselves are intricately connected to each other through underground fungal networks, as Erik Piikkila, a forester and ecologist, explains in the film. “You talk to a logger, and many know about the whole ecosystem: the way trees communicate underground, and the bugs and the fauna and the flora,” says Marquis. “They often know as much as biologists because they’re just in there all day.”

That’s why Silvicola, a title roughly meaning “of the forest” in Latin, is so fitting. The people who work in the woods have an intimate relationship with it that is palpable in the film. You can hear in their voices that they belong to the bush, not the other way around, although the lines of business and profit complicate how they act and feel. At the heart of the film is a paradox, a sense of aching regret and resignation, particularly from the older workers who had a hand in the destruction and mass-harvesting of forests, sometimes old-growth ones in particular.

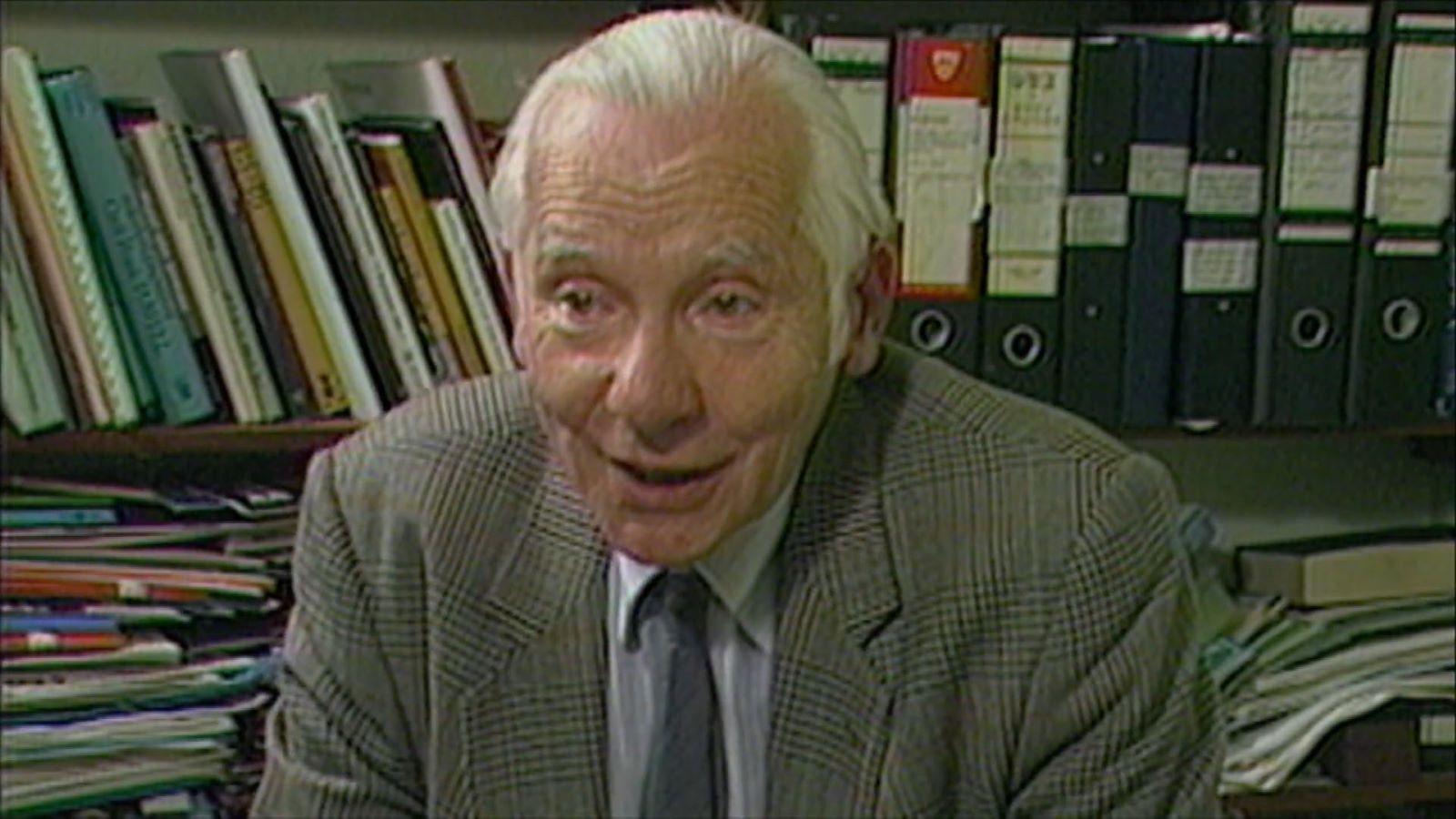

Joe Saysell, a retired faller, says in the film, “The cracking is so loud. To me, it’s that tree actually crying out…a horrible noise.” He calls it a “funny feeling,” with a resigned sadness in his eyes. He tries to explain all the ways he’s justified it to himself over the years, how he had to make a living, and even how some of his peers tried to implement more sustainable harvesting practices years ago. “We failed, because there weren’t enough people doing it. You look back on it all and say, ‘I wish it’d been different.’ But it wasn’t,” he says with finality.

Long before it dawned on white workers that sustainable practices were necessary, Indigenous communities had been practicing responsible harvesting and forest maintenance for generations. The film hears from two Indigenous experts about their ancestors’ legacies of forest-keeping, in particular, a practice called culturally modified trees, or “CMTs” for short. This careful stripping technique is not only a way of harvesting from trees without killing them, but, as the film shows, it also leaves behind a traceable legacy of generations past. In a revealing sequence, Todd Giihlgiigaa, a cedar bark weaver, demonstrates the peeling of a segment of bark.

“Our ancestors were foresters, and there was a lot of thought put into managing the forest,” says Don Svanvik, Namgis Hereditary Chief and CMT expert. In Silvicola, we walk with him through the bush as he examines the scars on old-growth trees, showing how the rings can be counted back hundreds upon hundreds of years. He explains how his nation participates in the industry, but doesn’t cut old-growth trees. It means losing out on money, but Indigenous workers know that it’s the right thing to do. With the rate at which machines have accelerated the irreparable destruction of ancient forests, Svanvik says, “If we destroy it all, I don’t think there’s any coming back.”

The film oscillates between scenes of the remaining peaceful, sprawling brush and the jarring movements of industrial machinery. The sound design heightens the contrast between the quiet of nature and the hums and cries of the machines. There are ones that plant the seeds for new trees and ones that chop down the old. The metal monsters are remarkably efficient at birthing and killing trees, but the one thing machines can’t do is speed up time. Many old-growth forests have existed for thousands of years, so the death of that kind of tree is irrevocable. The growing desire to preserve the last of these elder giants in the face of mounting machines is the beating heart of the film.

The industry has changed rapidly, and many jobs are being automated and going extinct. Silvicola closes on scenes from a logger sports competition where competitors demonstrate skills, such as rapidly climbing up trees, that were once the keys to a livelihood, but are now almost completely useless. Machines have eclipsed manpower. But no matter who is doing the killing, man or machine, it is clear that something needs to change quickly. The voices of protest from conscientious forest workers are crying louder and louder.

“When I was sharing meals with loggers, I would sense this internal dilemma. Often, those forestry jobs were the only ones that were available in these small, remote areas,” says Marquis. “They loved the forest, but they needed to feed their families too. The film is about this vulnerability.”