A Compassionate Spy

(USA, 101 min.)

Dir. Steve James

Even documentary wants in on the “Barbenheimer” craze. The summer phenomenon of Barbie and Oppenheimer taking the box office by storm gets some non-fiction counterprogramming with A Compassionate Spy. The latest feature from Steve James (Abacus) explores a compelling love story with a secret rooted in Oppenheimer’s Manhattan Project. The film tells an extraordinary element of the story about the USA’s rush to make a nuclear bomb that Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer only hints at. Audiences might not hear the name Ted Hall in Oppenheimer. He doesn’t appear as a credited character, but his part of the tale is worth knowing. Now he’s the star of his own movie.

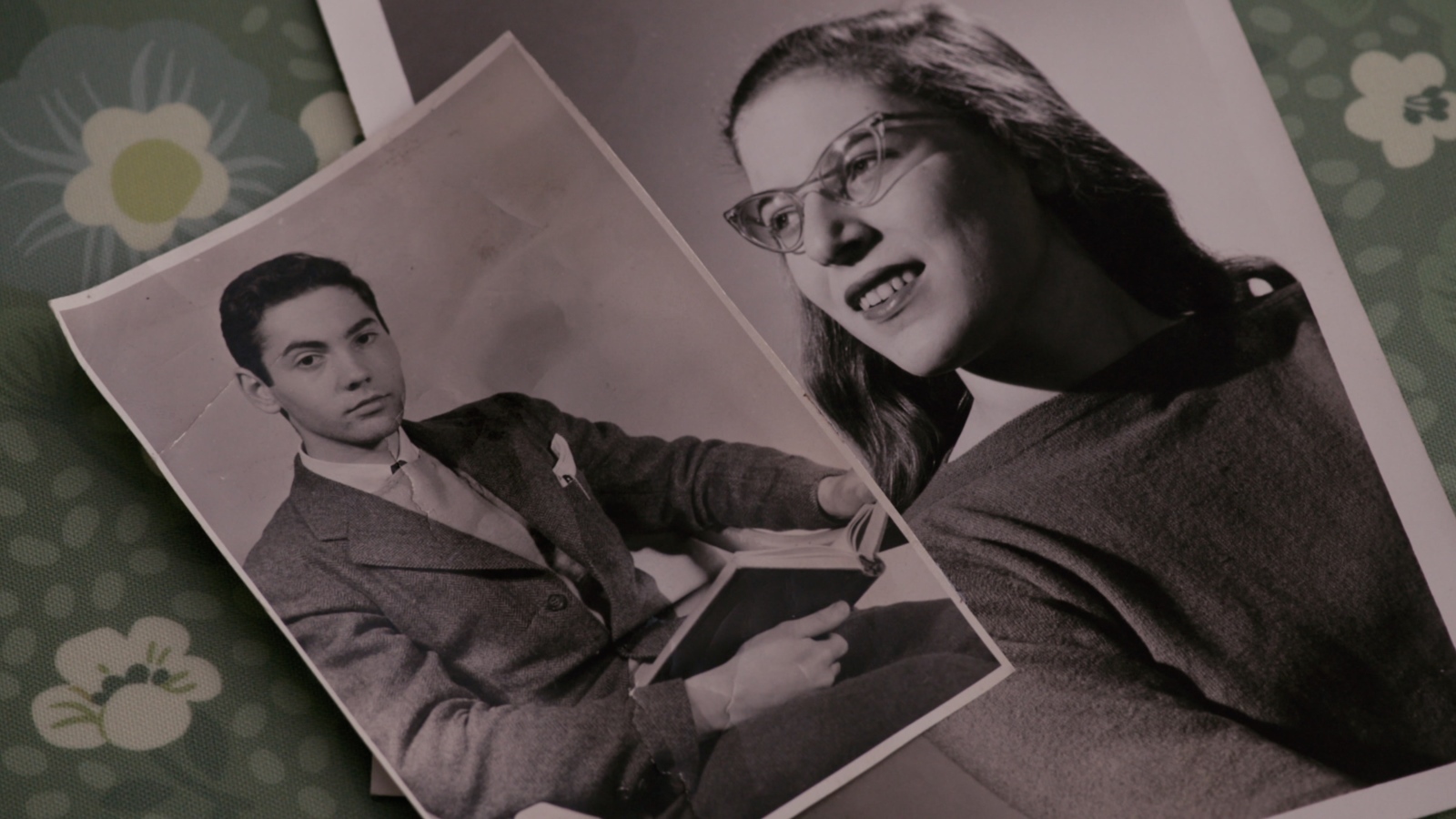

A Compassionate Spy shares Hall’s secret: during his time in New Mexico, he leaked details of the bomb to Russia. Hall explains how information he shared with the Russians was corroborated by fellow spy Klaus Fuchs, who does appear in Oppenheimer. However, with Fuchs being German, suspicion didn’t fall on the 18-year-old American. Hall died in 1999, but James’ film includes the interviews that the scientist taped to ensure that his story went on the record. His wife, Joan, also happens to be a great storyteller. She recounts in contemporary interviews the history of how her husband played a small hand in saving the world.

The film provides an extraordinary account of the moral complexity of the Manhattan project. Hall tells how he quickly realized the implications of the assignment. Recognizing the disastrous potential of the bomb’s might, Hall explains why he shared information with the Russians. The reason, he says, was to prevent the USA from having a monopoly on the most powerful weapon of all time. Once the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, his fears proved correct. The film appropriately does away with the backslapping that makes Oppenheimer an uneasy watch.

Safeguarding Against the Machine

Spy makes the case that President Truman dropped the bomb simply to make a point. This idea percolates in Oppenheimer, but A Compassionate Spy argues that Japan was days away from surrender. Instead, the bombs were a show of force to Russia and there’s fascinating insight here to the makings of America’s military industrial complex. Some might blame Hall for the Cold War (and James admittedly doesn’t really give much, if any, time to the other side), but the muscle-flexing with peoples’ lives lets Hall rationalize his betrayal of his nation’s confidence. Viewers might rightly agree.

The film features strong archival footage from the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, but those sights are eclipsed by the chilling reels from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While these images aren’t new (see: If You Love this Planet), they’re great windows into the psychology that compels someone to spy. His empathy for wartime opponents rings clear in the devastating images of two cities annihilated by the bombs. Similarly, images of scarred and mutilated Japanese civilians speak to the gravity of the newly-built killing machine.

While Oppenheimer adroitly handles the moral weight of building the bomb, A Compassionate Spy does the same with a twist. Besides wrestling with the idea of using his scientific aptitude to build something that kills people, Hall carries the weight of secrets. James clearly understands that viewers might object to Hall’s espionage. One character, for example, fiercely insists that Hall should have been executed for treason. Ted and Joan, however, share their experience of living in fear for years under surveillance by the FBI. Joan recalls strange visits from the “telephone repairman” and frenzied housecleaning binges to remove any incriminating materials. Re-enactments illustrate the secret meetings they had with friends, like Saville Sax, while navigating folks on their tail.

The Spy Who Loved Me

Among the surprises in Hall’s story is that the FBI interrogated him but never pressed charges. Joan shares how the fear of detection grew twofold when Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were tried and executed. She partly evokes wonderment if the Rosenbergs took the fall for her husband’s efforts, but observes that Ted thought they probably did “something,” albeit a deed that hardly merited death. But the Rosenbergs loom heavily in A Compassionate Spy as Joan explains that she and Ted were card-carrying Communists. Their participation adds another layer of vulnerability to the story. Like many people in the Los Alamos tale, the Halls are unabashed lefties. But amid political witch-hunts of the 1950s, their activities were another avenue for the FBI to pry into their lives.

While the film shares Oppenheimer‘s burden of pacing issues, it nevertheless offers a relevant story about the necessity of sharing information for public interest. Hall’s tale has contemporary echoes in the plights of publishers like Julian Assange and whistleblowers like Chelsea Manning. The film asks how long one should hold the burden of guilt when the passage of time validates one’s actions. It’s clear from Hall’s accounts that he stands by his actions, but bears damage from a lifetime of secrecy.

At the same time, A Compassionate Spy is a tender love story. While Ted’s taped testimony provides the whats and the whys for his narrative, Joan’s accounts are the heart of the film. While Joan says that Ted only told revealed his espionage after they became engaged, she would have made a good spy in her own right. She shares with James a message of sticking together through thick and thin as co-conspirators for life.

A Compassionate Spy opens in Toronto at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on August 4.