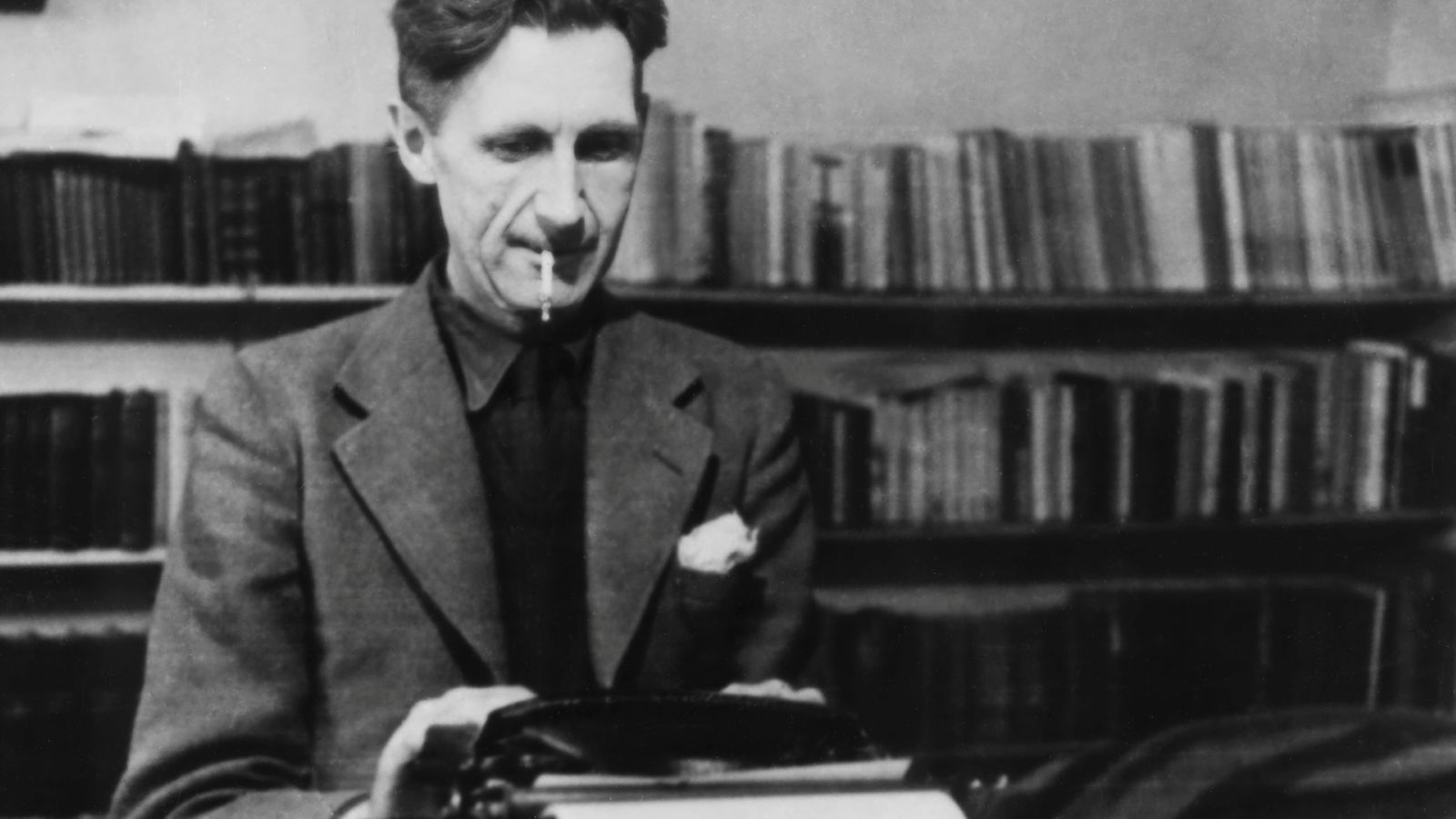

There was a time when Raoul Peck wasn’t very impressed with George Orwell. Before he made his stimulating documentary Orwell: 2+2=5, he had dismissed the famous British author as a one-note anti-Stalinist with a Euro-centric vision.

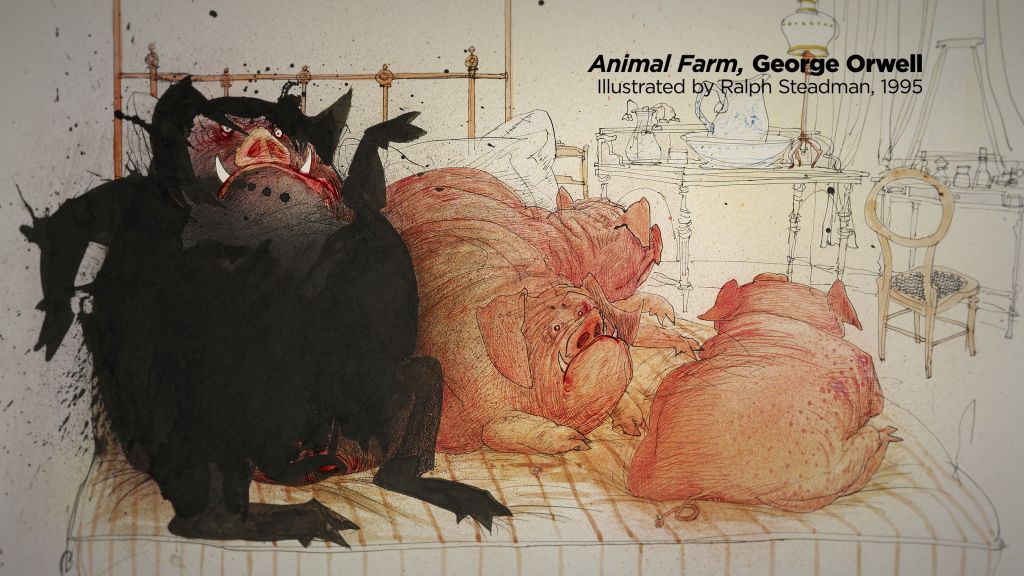

He doesn’t feel that way anymore. His new film mines Orwell’s work, film adaptations of it, the author’s letters, and essays for nuggets – read in voiceover by Damian Lewis – and images from around the world to argue that Orwell’s voice not only reflects his own era, but also resonates in situations all over the planet today.

“What I knew of him is what I learned in school: 1984,” Peck says, when I asked during an interview at the Toronto International Film Festival in September, whether his attitude towards Orwell changed while he was making the film. “There was a polemic around his name: he was used as an anti-Stalinist instrument when his analysis was more fundamental than the boxes people around the world have tried to put him in. When I reread most of Orwell, I rapidly discovered a fundamental relationship with him. I discovered him as a brother. His analysis was much more universal.”

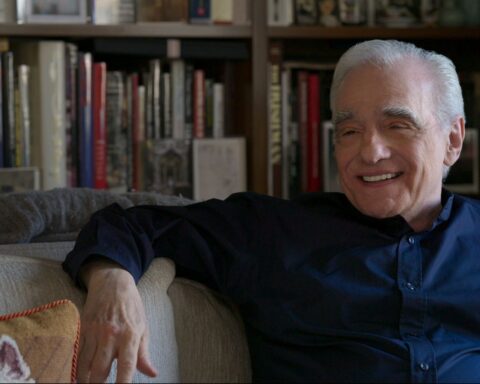

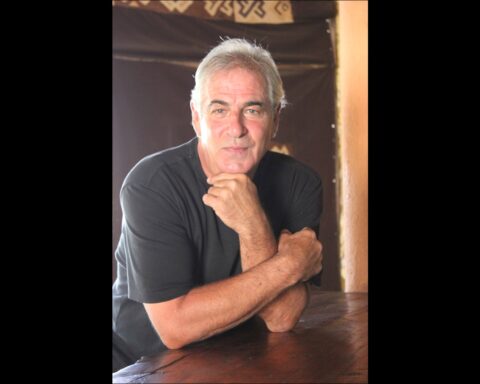

Haitian-born Peck has made dozens of works in film and television, including the Oscar-nominated I Am Not Your Negro, about the writer James Baldwin, and Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, on the titular photographer’s career in South Africa and America. Peck’s works are not biographies per se. Rather, they use his subjects’ images or words to probe memory and to challenge conventional attitudes towards history and the people who make it. All of his films are profoundly and pointedly political, which is not surprising. Like Orwell, Peck believes that all art has to be political, not just an individualistic expression.

“There’s no way that I can just say to myself, ‘I’m an artist now. I can do whatever I want,’” he says with conviction. “No, you live in a society. Society allows you to be an artist because others are working hard to give you the benefit of time and, potentially, of some money to make it possible to be an artist.

“So this is the way to give back to that society,” he continues. “The art doesn’t have to have militant words. Beauty can be enlightenment. Art can help any citizen to understand his life better and to feel better. It’s about understanding your role. It’s your duty to think about your world. [Art doesn’t exist] for your own little purposes.”

That self-centred attitude of some artists, he says, is reflective of the loss of collective values, which, in turn, he connects to the impact of social media in the digital age.

“Today we live in an individualistic world. People are inventing themselves on social media as if the purpose of all this is [their] own little self,” says Peck. “When you stand on the shoulders of people who fought for democracy and you pretend you’re alone in this world and that it’s all about you? That level of individualism around us today is insulting. You must never lose the collective part of you. We not only have rights in our society, we have responsibilities.”

In conversation, Peck is always this passionate, adamant even, insisting that the art of film should not only entertain, it should provoke. He never wanted to make Hollywood-style films. He has always been more interested in justice and content, a fact that puts him in sync with Orwell.

Some might argue that those values get in the way of nuance and complexity. But Peck insists that an obviously political film doesn’t have to be didactic and predictable. Finding the compelling narrative is the key to avoiding didacticism and predictability. He read all of Orwell to find that story.

“I write stories. I write screenplays. I always did both,” he says. “Learn your character and you’ll find the moment where there is a story.”

Peck found it in the last year of Orwell’s life when the author was trying to finish 1984, his influential dystopian novel about surveillance under the eye of Big Brother By then, Orwell understood that authoritarianism was not just about Stalin. He had seen it everywhere he had lived. He sensed that authoritarianism was not the only phenomenon to worry about – what was going in the world was not that simple – and he saw all the systems. Whether capitalism, classism, or fascism, he saw them in action.

“He analyzed what was going on through himself as a person – as a white police officer in Burma, as a fighter in the Spanish civil war, as a British journalist with the BBC,” says Peck, explaining what he learned from Orwell’s personal story. “He was always reflecting about the world around him and his world was not just Eurocentric. He was born in India, after all.”

Peck’s film makes the point that Orwell’s work is not all about then, it’s about now. Everything Orwell saw in his lifetime, everything that fed his perspectives and, definitely, everything that inspired his portrait of a totalitarian regime in 1984 can be applied all over the planet: in Myanmar, Haiti, Russia, Israel and, especially, in the U.S.

“We are in a world we have all the signs of an authoritarian regime. Make a list and you can check everything off,” says Peck. “Starting with the admiration of the incredible leader. When you see the [American] cabinet meetings, you could be looking at the Soviet Republic.”

Hitler, Peck implies, gave the current U.S. president the blueprint. Just as Hitler wrote everything he was going to do as the Fuhrer in Mein Kampf, Donald Trump signalled all of his plans on the campaign trail. Hitler’s adversaries thought he was a fool they could control. Trump’s antagonists called him a buffoon.

“And then when Hitler came to power, he attacked the media, the schools, the justice system, all the institutions,” Peck observes.

Trump has done the same, and at breathtaking speed. He’s also adopted 1984’s totalitarian regime’s strategy of Newspeak: in Orwell’s fictional Oceania, war is peace, freedom is slavery, and ignorance is strength. And two plus two equals five. As president, Trump just lies and lies, and his lies are called alternative facts. Taken as a whole, Trump’s is the kind of strategy that makes it hard for citizens to think straight, let alone organize effectively against his regime. Peck says it’s the political equivalent of carpet-bombing.

“When you’re carpet-bombing, you don’t let your enemies take a breath. You just derail their potential to resist or the possibility of thinking. Then they isolate you and attack you one by one.”

It strikes me as I’m listening to Peck that someone with his point of view must live a in a constant stage of rage. So I’m looking for something positive that motivates him to keep creating. Could it be, maybe, hope?

Peck wastes no time shutting down that idea.

“I never use the word hope,” he says. “It can’t be about hope. In history, there is no hope. There is only whether you resist or submit. Hope is almost a Christian belief that somewhere out of the sky someone will come and save us. What will make a difference is what [we] do or not do. What will happen depends on what you and the collective do. If you sit on your couch, nothing will happen.”