Ernest Cole, Lost and Found

(France, 105 min.)

Dir. Raoul Peck

Programme: Cannes Special Screening

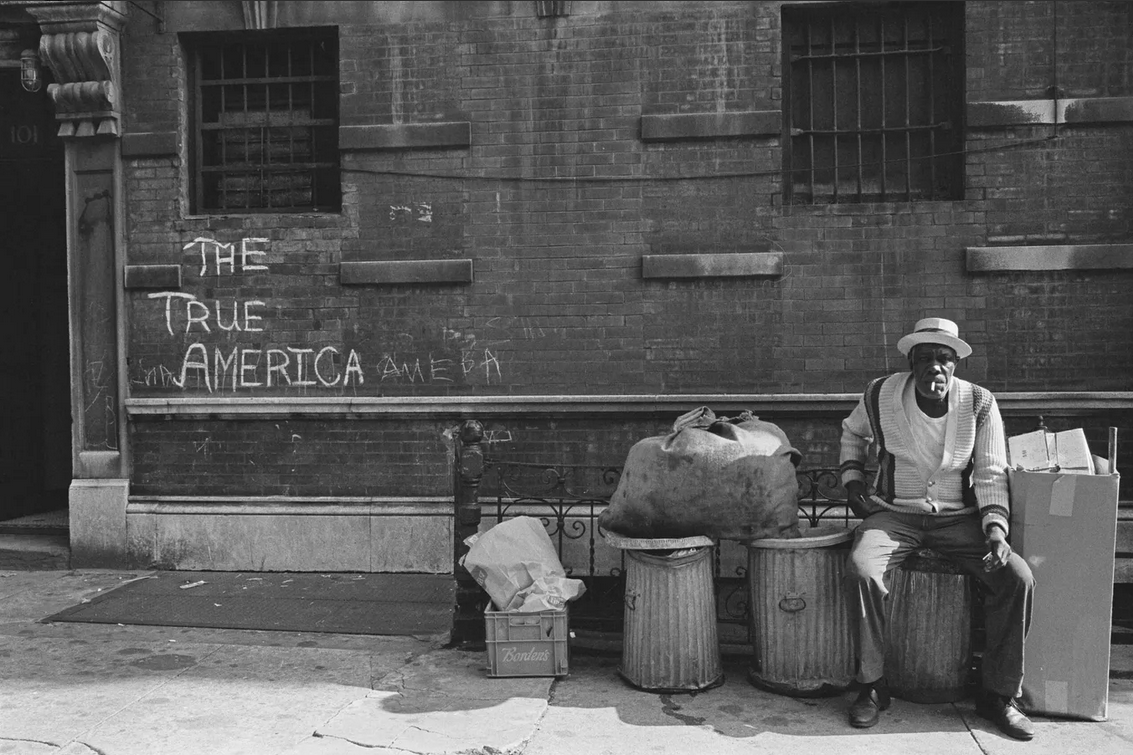

Raoul Peck, the legendary Haitian filmmaker (and recipient of an Outstanding Achievement Award this year at a different festival that seems to be taking a nap for a few months), has returned with another carefully assembled, beautifully composed and realized portrait of an artist. For his latest film, Peck turns his focus to Ernest Cole, a prolific South African photographer who helped document lives under Apartheid rule and the underclass in his adopted cities like New York.

Cole seems a perfect subject for Peck. They mirror each other in both the precision of their gaze and the way that even the smallest relevant details are given space and context to be resolved. Told with the assistance of interview footage shot for previous documentary, the primary source for Cole’s telling is Cole himself. (The photographer died in 1990 at only 49 years old.) From his own astonishing photographs, through to the eloquent articulations drawn from his writings and read in an almost soothing way by Oscar-nominated actor LaKeith Stanfield (Judas and the Black Messiah), Cole’s journey is exposed frame-by-frame, seen through the eyes of his myriad subjects and where he chooses to direct his eye.

Peck is no stranger to bringing to life remarkable figures for figures of African descent. His Oscar-nominated I Am Not Your Negro, a sublime telling of James Baldwin’s story that uses the subject’s own words and ideas, or his 1991 work Lumumba, Death of a Prophet and its 2000 dramatic sibling, both telling the tale of Patrice Lumumba and the struggles to achieve Congolese independence.

Cole proves a fascinating figure in contrast to these other two subjects, which says a lot, and is perhaps more akin to Peck himself. Cole’s gift was to be loud while being quiet, a paradoxical state that gave him access to shoot without compromise, but his results captivated the world’s attention towards the horrors of his native land and the oppression of the regime. Where Baldwin and Lumumba by definition took center stage, Cole almost reluctantly became the focus of the stories, centering as best he good what he was capturing versus who was documenting the story.

Similarly, Peck’s own voice is both overt and sublimated into that of his subject, the film presented in a way that feels at all times to be the vocalisation of Cole’s own private and public thoughts. Only a few external voices are heard from, including a relative who helps run a museum showcasing the photographs, and even he defers often to what we know of Cole’s intentions.

For not only is this a film that brings these images to a new generation, it’s also a bit of a mystery, if in the end an unsatisfying one. Tens of thousands of Cole’s negatives were stored, catalogued and preserved in a Swiss bank vault, rescued in ways that other images summarily disposed of from New York rooming houses were not. The benefactor(s) may remain anonymous, and answers frustratingly left hanging, yet there’s still a sense of almost bemused celebration that this cultural legacy wasn’t allowed to be erased.

The music, mixing Ellington-era jazzy swing with thumping Township jive from southern Africa, proves another major ingredient in the film’s success. The images by Cole themselves are remarkable when situated on the large canvas of a movie screen, the grainy black and white in particular benefiting from detailed examination right to the corner of the frame. The shift to colour film later in Cole’s career does make some of the images softer and seemingly less “artistic,” but the gaze is still there, the riot of colours remarkable, the subjects themselves staring back at us all these decades later.

While Cole had success during his lifetime, his later years were plagued by economic uncertainties and deep cynicism about the communities he called home. Being unable to return to his native country for so many years ate away at his confidence, and this instability and inability to continue his work provides a noticeable gap in his timeline. The thought of such a great talent forced to pawn off the very tools of his trade is heartbreaking, but Peck never revels in this tragedy in maudlin or manipulative ways.

Additional context about the Apartheid system, from books detailing specific required behaviours, to footage of Biko, Mandela, and so on, provide not only the examination of the man, but also the society that birthed him. Like Cole’s photographs, in just about every frame of the documentary, there’s more to see in Peck’s telling. This combination of the aesthetically rich and the politically nuanced sets the film apart. Ernest Cole, Lost and Found truly is a treasure beyond the images that miraculously survived, and none is better equipped to tell this complex yet revealing story than Peck himself.