aoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro may be the most ambitious and revealing film ever made about civil rights in the United States. Rather than a narrative history of race relations, it is a meditation on racism and the corrosive effects that threaten to rip a country apart. Told entirely in the words of the author and social critic James Baldwin, using his writings (read by Samuel L. Jackson) and a rich variety of source materials (interviews, Hollywood film clips, archival materials past and present), the film is a narrative and visual tour de force that gives Baldwin’s observations renewed currency nearly 30 years after his death.

Peck is a veteran of documentaries, features, and television work; his best-known previous film is Lumumba (2000), about the Congolese freedom fighter Patrice Lumumba. I Am Not Your Negro is partially based upon an unfinished Baldwin book titled Remember This House, a personal history of the lives and assassinations of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr., all of whom the writer knew personally. Using this and other writings plus extensive interview footage, Peck’s film becomes something much more—a historical throughline from the civil rights movement to #BlackLivesMatter, a reexamination of how the black image has been systematically distorted, and an inquiry into the dark heart of American identity. I Am Not Your Negro has been nominated for an Oscar in the Best Documentary Feature category.

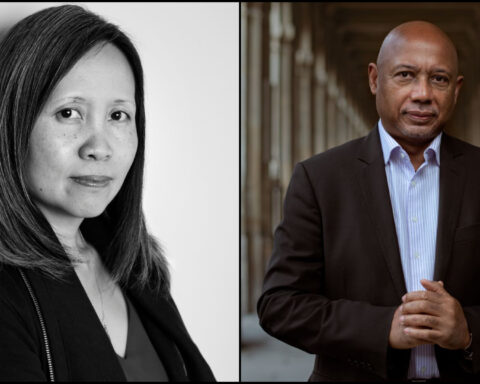

RP: Raoul Peck

POV: Steve Ryfle

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

POV: You were born in Haiti and raised in New York during the 1960s, when James Baldwin was in the public eye and helping shape the dialogue on race in America. How did he influence your development as an artist and filmmaker?

RP: I was very lucky to read him very early on. Probably I was around 16 or 17. It was like discovering a new world and a new way to understand the world. That fit with what I was already experiencing. The insight he was bringing was, for me, a huge revelation. I continued to have him very close to me throughout my life. The way he can analyze a political situation, historical situations; the way he can deconstruct filmmaking, Hollywood, and the whole culture of images, the whole creation of the black image—all these were a fundamental part of my work throughout all my films.

POV: Early in the film, Baldwin says, “I never really learned to hate white people, though God knows I’ve often wished to murder one or two.” His words underscore images of Fay Wray being tied up by black-skinned savages in King Kong. This dichotomy of text and the visual image is established right away. Sometimes it is ironic and sometimes it is literal, but it serves to amplify Baldwin’s ideas throughout the film. It’s something rarely if ever seen before.

RP: That was the creative joy of being able to use those incredible words. You are dealing with an incredible philosopher and…political analyst. And he’s doing that with images. So the choices were so multiple. You had to make sure that you were at least as fine as he was: to find the proper clip but also the proper amount and place it at the proper moment, so that not only the words and the images are strong, but the combination of image and sound and words creates something else, another level. That’s the trick in this film. Everything has a purpose, every single frame—when do you decide to stop it? Do you place it by something else? When do you introduce the music? Et cetera.

You cannot do this with every writer. It’s because [of] the language of Baldwin. It’s very visual, not only through his film critiques—and I think he’s one of the best film critics ever…[but because] his critiques had very strong political consequences. When he critiqued a film like Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, he wasn’t just critiquing the film itself, he’s talking to you about reality, of which the film is just a reflection… [of] a very tragic truth. So that’s why when I’m speaking with film critics about this film I’m in a very comfortable position because I feel like…it’s between Baldwin and you, much more than me. Because he asks you very directly, “Where are you in that picture? What role are you playing?”

It’s very strange; I’ve never had that with my other films…Film, you’re supposed to indulge in it, you’re supposed to abandon yourself in it. That’s what film asks of you. Believe in this story; I am creating character. But in this particular film the character is deconstructing what you are actually watching, and he is confronting you as an audience.

POV: Baldwin talks about the black image on film, a subject still relevant today. But more than how that image has been controlled and orchestrated by whites, Baldwin is concerned with the way he, and the black community, perceived those images of Stepin Fetchit and Uncle Tom’s Cabin and so forth, and the destructive effects they had.

RP: Exactly. Yes, you have both sides. The irony is that the very people who fabricated those movies never [saw] the other side. They never thought that people, in particular black people, could see it a very different way.

POV: How did you arrive at the idea to make this project?

RP: Sometimes people ask me and my response is that it took me 10 years to make the film, but in fact it took me much longer. Because once I knew what film it was going to be, all my knowledge of film and filmmaking, and all my knowledge about this country [the U.S.] or about the world or about being black came up again. All the books I underlined all my life, all the Baldwin books, everything came back. So it was much more than the result of a decision to make this particular film. It was also drawing and taking everything I have learned so far as an older filmmaker. This is the result, the same way the freedom I gave myself to say, in terms of creativity and finding the right form for this film, I wanted to go as far as possible. Even if I had to invent a form, which is what I think is part of this movie because I don’t know any precedent in this approach. I don’t know any [other] example of using exclusively the words of an author. That’s the only words you have in this movie. I don’t have anything I wrote myself; there are no talking heads explaining anything. It’s a direct confrontation with the text. I’ve said it before; I feel like I’m just the messenger. I’m in the background; it’s not about me.

POV: But you definitely had authorship in terms of form and technique. There’s a synergy with the material you’ve chosen, how you tell the story, and the explosion of creative storytelling in documentary films in recent years as nonfiction films have taken a bigger foothold in culture. Do you agree?

RP: Yes, well, partly I would say. Because what I felt I did is also the result of previous experiments I did. The [only previous] moment I remember telling myself, in terms of form, “I have to go as far as possible” was for a documentary I did about Patrice Lumumba [Lumumba: Death of a Prophet, 1992], where I gave myself the same freedom. I remember very clearly that at the time I was one of the few who decided to include a voice that was partly me but was mostly a character that I invented, and who was telling the story. Experimenting in that, that’s when I discovered that I could not use a narrator; I refused to call it that. And I knew that in order to work it had to be a character, and that’s exactly what I did with Sam Jackson [in this film]. I knew that if I used a narrator I was dead; the picture wouldn’t exist because it would have created a distance between the words and the meaning and this voice that you are hearing, because you are also seeing James Baldwin speaking to you, with his own voice. So how do you go from one to the other? The only way to do that with the magic of cinema is to…create a character.

POV: What level of access to Baldwin’s archives did you have?

RP: That’s also the story of this impossible film because it needed all those incredible moments. The estate basically gave me access to everything, whether published or unpublished, private letters; I could use anything I wanted, which is unprecedented. Usually you buy an option for a book, or for two books, or an article, or a chapter of a book, but never for a whole body of work. I don’t know any similar situation in the whole history of film unless it’s your father or your family. To have this total access—and by the way, without any pressure. Any other estate would have come back to me after two or three years and asked me, “Mr. Peck, where is the film? You are blocking all rights on James Baldwin.” Because nobody else could touch them. There had been inquiries within those 10 years but they would always refer them to me, and it was my decision to say, “Well, I need this part, you can’t use it.”

POV: You also obtained access to footage from Baldwin’s 1968 appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, which becomes integral to the film, as well as from many other sources, including the films Baldwin references.

RP: That was a whole operation unto itself. This film would have been unfinanceable if we didn’t have what is called Fair Use. But Fair Use is a very tricky rule. We had to have a lawyer…for a whole year, working with us on every edit, because it has to be very precise, what you can do and what you cannot do. There’s no way you can say, “I’m going to do the whole film Fair Use.” People will sue you. You have to make sure you have a credible reason and explanation for why you use that particular clip or not. The great thing is that Baldwin himself quotes those particular films or those particular actors. When he says John Wayne or he says Doris Day, that opened the door for me to use that footage. But of course, some of it I had to pay for, otherwise it would have been [risky]. So…if you can deal with it in a creative way, it just makes the film even better.

[Our attorney] would tell us, “You have 12 seconds of this. You are pushing the envelope too far.” We didn’t just cut those 12 seconds. No, we worked further and found a more creative thing that would be even better, to go around it. So all this is a succession of production situations that are unique. And they were possible because I produced the film myself. So, I knew when I had to go find more money, and where. I had to go to people who trusted my work, who would not come and say, “Raoul, it’s been four years, where is the film?” That would have been impossible for me. I made another film when I was working on it. But to be able to leave the editing table for two or three months and come back with a fresh mind…this was a luxury that you very rarely have. The richness of the film comes from the ability to add all those many layers, layers that you cannot shortcut. You really need the time to come to that.

POV: You mentioned experimentation with form. Were there any other films or filmmakers that influenced your approach?

RP: In terms of people that were very influential when I was a young filmmaker, and who really opened to me all the type of freedom I gave me myself, there are two prominent ones, Chris Marker and Alexander Kluge.…[I Am Not Your Negro is] the kind of film you cannot just put in a synopsis, there are too many different levels and images and stuff…but one of the examples I would use was to say it’s a mix between The Celluloid Closet and Concerning Violence.

POV: Baldwin expresses one of the film’s main ideas early on, when he says—paraphrasing here—that for a young moviegoer, a child of 6 or 7, it came as a shock to be rooting for Gary Cooper as he killed the Indians and then realize that you are one of the Indians. That the country where you were born does not accept you. This dialogue is heard over images of Ferguson.

RP: I learned that very early, and I think every young child…from the third world also learns that very early. Anybody who belongs to a category that is not centre stage in Hollywood films feels that, at different levels. Sometimes you can’t put words on it; you don’t know where it comes from, but there is an unease. Some people, they learn how to deal with it. I did a screening of The Terminator in a small village in Haiti, and the DVD I had was in English. I saw all these kids watching The Terminator as they would watch themselves on the screen. But at the same time, when you talk to them, they know this is white people with a white story, etc. But they find a way to [make it] their own. So as an audience, when you don’t have your own image on the screen, you do find a solution to find your own story or to fabricate your own story…You’re watching the film on very different levels, and…you never let yourself totally go, because if you do, you are in a lie. Because you are not part of the story, not like it is portrayed.

It’s something you learn. And one of the particular examples in the film is about The Defiant Ones, and what Baldwin says about the liberal crowd. When Sidney [Poitier] decides to jump off the train, the [white and black audience] reactions are twofold for the same film. One was happy because it gave an image of the world that was a great one, one of brotherhood, one of humanism and love and etc. The other one was totally pragmatic, saying, “Get up, get back to the train, you fool!”…So, it’s the same story but with two opposite points of view.

I think a lot of people went through that, that discovery. You know, you don’t wake up in the morning and say, “Oh my god, I’m black.” Or “Oh my god, I’m gay,” or “Oh my god, I’m a woman.” Life teaches you that. Life confronts you with this thing on a daily basis. So it’s a learning process. The only ones that don’t have to go through this…[have]what they call white privilege. Because you don’t need to think about it; you own the world. You won, so you’re defining everything else, so there’s no reason to question that. But that is not the reality of the vast majority of people in the whole world.

POV: Baldwin’s words reflected on the future, our present day, as well as the past. You worked on this film over a number of years; when you started, Ferguson hadn’t happened yet, Trayvon Martin hadn’t happened yet. Yet these and other events are present in the film.

RP: That’s the thing. Baldwin’s analysis was fundamental; it’s always true. And that’s the purpose of the film: to show the proper way to deconstruct this reality. That was the crazy thing about it….Structurally, nothing has changed. In the way people are experiencing each other, nothing has changed. Jim Crow is still here; it just takes different forms. Any statistic you take about poverty, wealth, housing, schools—each one of those numbers are worse than it was in the 1940s, at least relatively [if not] absolutely. This is the reality. Anything that came after that, whether it’s those killings, it’s just further proof…So this film is not so much [about] being prescient. For me, it’s almost a last warning. Because you cannot put it any more precisely than it is in this film.

This film cannot leave you innocent. I don’t think you can watch it and say, “I don’t understand” or “I still don’t get it.” No. You get it. Everybody gets it. The only question left is what do you do about it. Whether you do something or you don’t do something, you are going to pay a price. That’s what Baldwin says. He said, “You cannot lynch me and keep me in the ghetto without becoming a monster yourself.” That’s what it means when he talks about “moral monsters.” So the person, whether [as] a perpetrator or just a silent observer…his life is also part of the problem. And this is what the film says, ultimately.

I am Not Your Negro opens in limited release Feb. 3 and in Toronto at TIFF Bell Lightbox on Feb. 24.

Read the POV review of I am Not Your Negro here.