The best part of the latest monograph put out by the Toronto International Film Festival Group is the last—Pierre Perrault in his own words—where the passionate, sometimes in-your-face documentarian ends up sounding dangerously close to a stuck pig. Thank goodness then for David Clanfield’s painstakingly careful and thorough 152-page examination of Perrault’s prodigious oeuvre.

In Perrault and the poetic documentary, Clanfield admits that he has only scratched the surface in terms of making the great documentary filmmaker’s work accessible to a non-Québecois viewer. Indeed, Perrault’s work has barely been shown to a Québecois audience with some of his films buried in late night TV scheduling or postponed for political reasons. “But I hope I have conveyed at least some glimmer of what Perrault did,” writes Clanfield, “to turn the technology of direct cinema into a cinema of experience, to transform found images and found speech into memorable monuments of a culture, to convert marginal existence into the expression of a nation, and to define the role that poetic documentary can play within a national cinema.”

Perrault studied as a lawyer, initially, but soon realized that his heart lay elsewhere. “I liked reading and hockey,” he notes, so, “I applied to Radio-Canada.” He was hired as a radio scriptwriter, a position that led him to making shorts for television and then to the ONF/NFB to work with Michel Brault on the pivotal Pour la suite du monde, a film documenting the last beluga to be caught on the island his wife Yolande grew up on.

This film holds traces of what would obsess Perrault for the rest of his life: the quest for an indigenous identity. All of his subjects, in one way or another, validate the idea that identity is tied to one’s relationship to the land—notwithstanding distant connections across the pond. In fact, digging for roots in France proves a disappointing venture in some of his documentaries like Un pays sans bon sens!, and drives home that identity is found at home, and in the country, not the city.

This distinction sets up an elegiac tone to some of Perrault’s work as he seems to be chronicling a dying culture. But Perrault steadfastly revisits the fading rural lifestyles in his work, and one subject in particular, Hauris Lalancette, seems to epitomize Perrault’s tenacity in the face of overwhelming odds.

Hauris was a farmer who stubbornly refused to yield to corporate incursions and ran as a Parti Québecois candidate in the 1973 provincial election. Perrault’s film Gens d’Abitibi shows Haurison the campaign trail giving impassioned speeches about resisting foreign economic takeovers that force the Québecois off their farms and into factories and mines. But no one seems to be listening. After a devastating election loss, Hauris returns to his farm to confirm “his own sense of belonging. This is what Perrault calls “the sublime Olympian moment.”

In an interview a few years later, Perrault staunchly defends Hauris, while also agreeing with the critics who termed Hauris a squealing stuck pig. “But Hauris is actually unbearable. His is a stuck pig, a man who was told, ‘A kingdom awaits you’ …who realizes that his victories as a man of the soil are being forgotten… I am utterly fascinated by Hauris struggling and refusing to die to preserve his dignity as a common man, even if at times he gets to be unbearable to the delicate sensibilities of those reared in the written tradition.”

In the same way Perrault defends Hauris, he also defends his right to make real films that eschew Hollywood fiction, films that again and again point to the failure of the Québecois to resist domination by outside economic forces. For Perrault no autonomy can be had for a people willing to sell their soul. “Does the soul always follow the money?” asks Perrault rhetorically. “Maybe the merchants will always have power over our lives, but do we have to abandon, yield, and surrender the city, hand over the land of our pioneers who cleared it, because the sellers of bikinis and toothbrushes are promising us other horizons?”

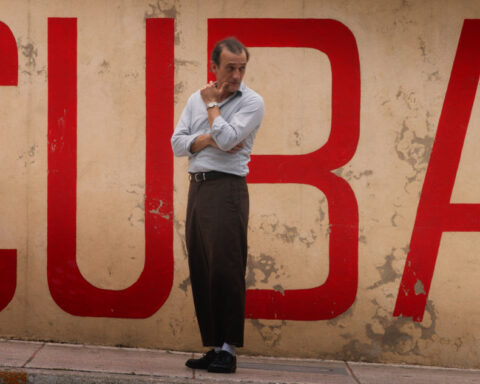

Yet, for all the political verve of Perrault’s work, the images that stand out the most in Clanfield’s monograph are those of the young documentarian standing in tidal water—“What a fantastic experience it was making a film with one’s feet caught in the wrack weed of the mud flats when the tide is running in at terrifying speed!”—or falling in the snow towards his destiny:

The determination and spunk of a man on a quest (popular or not) is fuel enough for any documentarian. If nothing else, Perrault captured iconoclastic images that define the man and a nation.