Jorgen Leth: Translucent Being

The Five Obstructions, a movie made with (and despite) Lars Von Trier, has pushed Jorgen Leth further into visibility on the global stage but there are long lines of light that led to that renowned collaboration. His coolly observational moments are the result of a restrained celebration, an embrace that knows the cost of refusal. In film after film, Leth returns as the spurned lover, burned, left out to dry, but back again. The pleasures he offers are more deeply felt for having been denied him; earned, they surprise him, and so he is determined more than ever to find the life in these passing moments, and to keep passing them right along.

In A Moment of Play (82 minutes, 1986), the camera is curious, inviting us to look, taking these in-between moments of playtime seriously. Leth’s filmmaking is up-close-and-personal, filling the screen with faces that grimace and hope and sing, with hands that carve and roll balls and beat drums. Over and again he starts close, so very close, to make us part of the scene, to connect these bodies with our own. And then he pulls back to show us where we are. Oh, a street in Bali. A sunset in Brazil, Spain, China, Denmark, England.

The voice-over belongs to the director and always begins in the first person. “I pass the time away. I disappear into my dreams. I must do it right.” No matter that we are watching young children playing with a baby crocodile, a Californian bouncing a ball off his body, young boys shooting bows and arrows. It’s me. It’s always me. His voice-over, his presence, is continuity and explanation. But did I mention how beautiful this film is? Not just rope skippers but twilight against a New York skyline. It’s not necessary perhaps; he does it for pleasure and part of the pleasure of looking is beauty—the heavenly light from the attic window which turns a boy’s toy train into dreamscape. And how graceful and beautiful these bodies are, as if the body was made for play after all, and not work. On the rollerblade track everyone turns to their own Walkman, each body carries a song of its own which sings in the presence of others, producing not cacophony but the simple addition of pleasure.

“We envisage a playful, elegant film. One shouldn’t be afraid of repeating oneself. On the contrary; great artists return to the same themes. Without wishing to compare ourselves to them, we will adopt the same working model. Simple means. Black and white film. Highways, motels, (Robert) Frank, Edward Hopper, and then Leth and Homberg. Today at around the turn of the century. What does America look like when we seek out the visual templates that are so expressive?” Here Leth writes about New Scenes from America, an update and revision of his 1981 short 66 Scenes from America. Each scene proceeds episodically, as a series of postcards, looking at iconic moments of Americanarama (cocktails, beach scenes, musicians and actors) many named in a hilarious straight man accent provided by Leth himself. Celebration or denunciation: Leth leaves it up to his viewers.

Strange to think of The Five Obstructions (Jorgen Leth and Lars Von Trier, 90 minutes 2003) as a collaboration. An oedipal saga, a confrontation, a love letter between two (the only two, the lonely two) who can’t bear to speak these words—Oedipus, love, confrontation—between one another: this is the obstruction that lies behind all the rest. The film examines the director as superstar trickster. Lars Von Trier, haunted by his own talent, has established for himself a series of prohibitions over the years. The Dogme rules are the most well known, but there have been others underlying his films from the very beginning when he was a technical geek (how did he DO that?) but found the work empty and unsatisfying. When there’s this much talent involved one must invoke again the taboo, the moral dividing line, and the results have been splashed across cinema screens around the world. Needless to add that this work has been born of suffering: Von Trier is a traditionalist after all, like every innovator.

In The Five Obstructions he appears as devil’s advocate, reaching back into his own past to pluck his cinematic father Jorgen Leth (once his teacher, the source, the body where cinema resides) and asks him to remake his own film The Perfect Human (13 minutes, 1967) five times, each with a new series of “obstructions.”

Why is happiness so brief?

“Jorgen you’re looking great; that’s not so good,” remarks Von Trier as Leth makes his way back after the first obstruction is complete (no shot over twelve frames, to be shot in Cuba without sets). Von Trier is looking for a way to break the habit of being human, the shell of personality we carry around as armour, in film after film, in obstruction after obstruction. But Leth sails through, apparently untouched. Comrades of despair, their correspondence before the movie (the off screen space, the prelude) has dwelt at length on their lingering depressions. From this stricken, lonely place they have found a way back into the world, Von Trier into the emotional strip shows of staged drama, Leth into globe trotting, watch and wait documentaries, each allowing themselves that rarest of pleasures: to celebrate and then to share their own obstructions.

The films of Jorgen Leth are available from: Danish Film Institute, Landemaerket26, 1119 Copenhagen K., Denmark,www.dfi.dk

Arna’s Children: A Tender Brute of a Movie

Arna’s Children (85 minutes, 2003), is tenderly tough, merciless in its compassion and embrace. It made me cry. From the opening frames it is clear that these are necessary pictures. This is what the news would look like if it were the province of filmmakers instead of corporations.

How to make a picture of this lost Palestinian State, from which we have already seen too much? Who hasn’t weighed the evidence of the camera crews, the professional lookers, paid to watch what we can’t? What these too many pictures have shown us is the view from above. The aerial shot, the weightless ascent of a crane, and the public building dramatically floodlit at night providing on-location backdrops. These are inventions for the ruling class, supported by the media conglomerate elite.

We return to the occupied territories in Arna’s Children as if for the first time, our feet on the ground, without official statements on this Inferno tailored for export. Instead, we are guided through the daily life of the siege by our Virgil, by Arna, the indomitable Jew, the Israeli who spends most of her hours on the wrong side of the dividing line, protesting the invisible brutalities of state and their simultaneous recoding.

She builds a modest theatre for Palestinian children in Jenin, and asks her son Juliano MerKhamis, the one who will become a filmmaker despite himself (to each his conversion), to teach them how to stage their own stories. Refuge, respite, representation.

They’re building it here? Here?

The other side, the enemy, are labeled “terrorists.” How can we forget: as late as 1988 the US State Department still named the African National Congress one of the “more notorious terrorist groups.” Mandela was a prisoner then. Only popular pressure—the grind of marches and meetings, pamphlets and speeches—changed all that, just as this film hopes to offer its modest, moving proposal towards a clearer understanding of a Palestinian state.

This is intimate politics. Sure, Arna makes a speech or two, but mainly she leads her students towards expressions of their own: first the tears, then the rage. She never says, “I can’t anymore, it’s too much;” it’s always, “what now?” She lives this struggle at each tick of the clock; saying hello is a political act.

One morning a regular student doesn’t show up and the next day Arna asks why. “It was the Israeli soldiers,” he says. They destroyed a home in his block, and his house fell into ruins as well. There is a picture of the disconsolate boy sitting in the rubble of what had been home only that morning, and there is no need for explanatory voice-overs to tell us that events like this happen only in war zones, or that this collateral damage is too commonplace to rate a place on the CNN ticker.

To make this film, Arna’s son returns years later, a step slower and a little greyer, armed with footage from the past. Everywhere he turns in these ruined streets, “Arna’s son” is the skeleton key opening faces around him. For one aged woman, clutching her shawl, memories of Arna are her only happy ones.

He has come back to speak to the young boys we saw in the film’s opening half. But it’s difficult. After the hug and smile and “come in, come in,” there is an awkward pause. Has too much time passed?

The director wonders: what are they doing now, and why? It turns out that Ashraf died during a street fight, while Alla now leads a semi-military group. The boys have grown up. Is any of it a surprise? Raised in rubble, with a bad situation growing worse, and all those funerals. We are taken behind the scenes, where the Palestinians snipe at Israeli patrols, set bombs and trip wires, engaged in a one-soldier-at-a-time guerilla war.

Yussef is a suicide bomber. When I read about the bombings in newspapers I could never understand their reasons. Photos tell you nothing: always the damaged remains of a café or bus and inserted in a frame of its own, superimposed, a family snap of the terrorist/freedom fighter. But here, in this movie, at last, I saw it: what else is there? Faced with the naked exercise of Israeli power, condemned again and again by the United Nations and a fleet of human rights organizations who offer judgments without aid, what else?

At least, there is this movie. This bearing witness when so many have gone before and looked the other way. If you can tear your eyes from the White House, the Knesset, the legacy of Arafat, this is a life’s story and a nation’s.

Arna’s Children is available from:

Trabelsi Productions

PO Box 20662 Tel Aviv 61 203 Israel

info@firsthandfilms.com

www.firthandfilms.com28

Slouching Towards Baghdad

There are many who use the word “Bush” like past centuries deployed the name of “Allah” (or “God” or…) as a way to stop thinking, as a shorthand for some higher function gone terribly wrong. How could Bush kill my son? How could Allah take away my home in a flood? Even in the smoke-free, vegetarian swarms of left leaning politicos the burning bush appears as totem and mirage, disguising the crucial fact that the policy of American empire has remained unchanged for half a century no matter who appears in the newspapers every day.

The American republic was formed in a deliberate act of genocide against the native Indians who called the land home long before Protestants took up arms against them. The original thirteen colonies began expanding as soon as the ink was dry on the Constitution (a document written by white slave owners to protect their property). They managed to seize or fight or swindle large tracts from the Spanish, Mexicans and French to establish their “manifest destiny” over the vast majority of North America. Venturing offshore, they created a Mafia paradise in Cuba, grabbed what they needed of Panama and ruled with an iron fist in the Philippines.

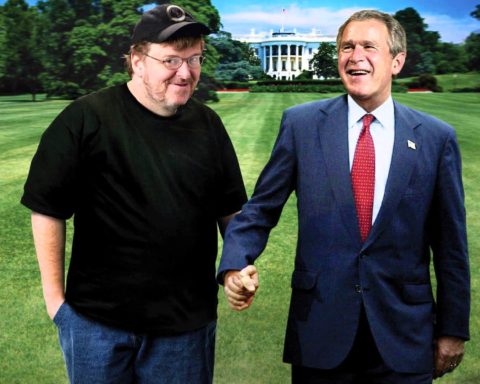

Their latest venture in Iraq is no different. If there was no oil, there would be no war, and certainly no occupation. Look how quickly they allowed Afghanistan to slip back into opium production, misogyny and warlord rule. So it made me uneasy when I saw “Bush” appear so prominently in Michael Moore’s Cannes-award-winning,100 million dollar box success story, Fahrenheit 9/11. Sure the guy’s heart was in the right place, but why beat around the Bushes?

Despite his own millions, Moore remains a populist, and he tries to do for American foreign policy what he managed with such élan in Bowling for Columbine, to provide both a recounting of once current events, and their structural underpinnings. Why is America at war in Iraq? What does that have to do with the airplanes of 9/11? In a brisk montage he takes us through the Florida electoral fraud, the vacationing president, the ludicrous marriage of Iraq with 9/11 and the failure to find weapons of mass destruction. He also takes pains to elaborate on the relations between two oil families, the Bushes and Bin Ladens, and shows Bush senior pimping for his Saudi counterparts, armed with daily CIA briefs. Moore’s pursuit of Bush wins him this insight: American foreign policy is an extension of class privilege. As Chomsky has stated time and again: poor people subsidize the rich.

While the film’s first hour is a model of incisive clips and commentary, the second hour is less clear. It’s one thing to point out that no weapons of mass destruction were found in Iraq, but Moore clearly has no idea of how to present the occupation. This would require at least a cursory understanding of Iraq. Instead he retreats to the recruiting stations of America, and specifically to his hometown in Flint, Michigan where the class war is being undertaken (again) under the disguise of patriotism. We go to the mall where teenagers without prospect (the economy has failed them, a victim of outsourcing and globalization) are being feted by recruiters.

But would it be too much to point out that the worst of the occupation is being felt by the people in Iraq, and not the families who have lost soldiers there? To Bush’s glib reason for the existence of “terrorism” (“They hate our freedom”), Moore offers up the cost of defending it. But what about those Iraqis who had to survive under a dictator armed and initially supported by the United States, then had to suffer American-led sanctions which saw more than five hundred children die each month for lack of potable water, before going through an invasion, nightly raids and curfews, electricity black-outs, chronic water shortages and massive unemployment? Yes, the profiteers are shown in Moore’s film in all their preening self-justification (Oh Haliburton! Oh Bechtel!), their multi-million Pentagon contracts firmly in hand; but what about the real cost of their plunders: the heaps of dead, the prison tortures and slaughter?

What Moore’s flick never manages to unwind is the solipsism of America. This is a country where other countries appear in the news only when they are being invaded. For all his shooting (or borrowing) of footage in Iraq, there are no Iraqis interviewed; none appear except as grieving mothers, their horror at lost sons and daughters another trophy moment for export. No reminder that the “Vietnam War” was called “The American War” by the other side. That “the other”—Vietnamese, Cambodian, Nicaraguan—is as real as one of those New Yorkers who died in the Twin Towers. This is something Moore is unable toachieve. While his movie remains a challenge anddefiance of much conventional wisdom, theempire still lurks behind his editorial decisions.The Iraq war for Moore is finally about the sons and daughters of Flint, and not about those unnamed others, the collateral damage of money and power.

The films of Michael Moore are available through:

www.michaelmoore.com

Our Peasants

The title is already a picture. Profils Paysans: L’Approche (Peasant Profile: The Approach) is aninety minute film by Raymond Depardon, photographer and doc-maker.

As soon as the movie opens, my expectations are confirmed and thwarted. Sure enough, we are traveling in the French countryside, and the exemplars of a life no simpler for want of an Internet connection are almost all past the age of retirement. Though there is no retirement from this way of life, only the grave. What is peculiar is the compulsive chatter of the director, in his beautiful French voice. (Was the voice-over invented to allow us to hear the French language without the distraction of the mouth, the red herring of the body?)

The journey begins with a sad string accompaniment, but no sooner have we traveled a few seconds then the voice begins, impatient to tell stories that need to be told, or at least, the frames of stories, their ghostly contours. The voice announces the opening of a journey in the third person. We haven’t met anyone yet, but on this side of the camera, the watchers are multiplied and the look is already a consensus, a compact. It is “our” journey, though it’s clear that while the viewer may be privileged (or bored or irritated or enthralled) to look through the eyes of this multiple, “we” are the property of the reproduction, the apparatus. The viewer has already come too late.In

The first subject is introduced, an elderly farmer shaking with Parkinson’s, but sternly capable of keeping her own house and animals. The director continues to speak (of course!), pronouncing her name, a recent tragedy, the barest sketch of her present circumstances. She reads through her paper, trembling as she turns the pages, and never looks at “us.” What I am waiting for is the decisive moment, never mind that such moments are missing from my own life which proceeds in a haze of indecisive moments and vague gestures. In the cinema I am granted that rarest of blessings: intimacy without consequence.

As I watch her reading the morning paper I wonder, “why this shot and not another?” What is being revealed here? What special, private moment has been stolen from the memories of this stranger, who will be laid open like a cadaver in a morgue for the viewer (for us!) to satisfy our restless appetite.

She says nothing. The director tells us that a friend will come to visit, and when he does, they speak a language even Depardon cannot understand. Of course, he films it all. They keep their secret, their private lives, for themselves.

Depardon moves right on down the road. He could wait in order to break her down, torment her with the expectation and weight of the camera, which is heavy precisely because “we” are also waiting. The camera carries its imaginary audience in the lens, who demands entertainment or confession or, though it’s unlikely in a documentary, beauty.

But Depardon refuses this circuit of desire, content instead to chat in voice-over while his subjects eat, read, make coffee, look on sullenly—as if they were the audience, and we the subjects. A new kind of verité emerges. It’s not cinema verité, with its “first thought-best thought,” transparent-truth ideologies, but a verité cinema, which carves out a space alongside its subject, who are neither elevated nor depressed through interactions with the apparatus. The framing is careful, almost delicate, and above all, frontal—like an Elizabethan thrust stage. There’s nothing to hide here. It’s important above all to provide context: the camera is set back from its subject to allow the windows and roof and chairs a chance to have their fifteen moments of fame. And there shouldn’t be too many shots, never mind montage—these are peasants after all, they can’t afford montage—they belong to a world of mise-en-scène, of patience rewarded after waiting for harvest.

The farmers are full of small talk, working out the details, the necessities: fixing a cut on the hand, bargaining today’s price for calves, accumulating firewood. In place of feelings, there are inseminations to consider, bulls to be borrowed. The actors are old enough to play themselves, unrehearsed and unadorned; no one puts on their best suit.

The fourth wall, the space we are granted, is not an easy place. The subjects are wary. Clearly the camera does not belong here, and neither do we. This is not city life, where strangers climb in and out of view on every street corner. Depardon refuses to make the way any easier, to bring us any closer. He leaves in all the looks towards the camera, which occur dozens of times, and there is always his voice which, while apparently dishing information (“We are back again in…”), marks a border, reminding us how much is being left out. It’s like listening to your favourite rap song while watching the VU meters in a mixing studio. Depardon’s remarks make an object of his voice, pulling us out again and again from behind his camera and its veil of reproduction.

It is a reflection, finally, of the division between private and public space. The farmer’s son hides in his own room, preferring the consolation of anonymous pictures on television to the immediacy of his own capture. When he is introduced, he is clearly posing; camera ready, the guard is up: he is ready for his close-up, but for how long? Verité cinema: a reflection of reality and the reality of reflection.

A two-day negotiation, hard bargaining for cattle, occurs over a kitchen table. When the terms, which have never changed, are finally settled, the old farmer walks away from the departing truck back towards his house, as the camera jerks in an awkward pan towards him. He stands there, peering into the lens, granted at least the dignity of the last word, which is also a comment on cinema, on the documentary. (Admission, dismissal, accusation.) He turns to us, to the lens, and announces, “Those sellers are all the same. Tougher than the rest.”

The films of Raymond Depardon are available from:

Claudine Nougaret for Palmeraei et Desert

18 bis, rue Henri Barbusse 75005, Paris France

palmeraie.desert@wanadoo.fr