Do audiences need another Bill Cunningham documentary? It might be an odd question to ask when there’s yet another adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma opening in theatres. However, as with the new Emma, the latest Bill Cunningham doc reminds us that some characters are well worth revisiting. Cunningham, the man best known for his signature fusion of fashion photography and street documentary, could probably fuel as many films as Emma Woodhouse can.

The Times of Bill Cunningham, the feature directorial debut from Mark Bozek, adds new layers to the life of the late photographer who gained a new legion of fans with the terrific 2011 documentary Bill Cunningham New York. Bozek’s film goes deeper into the photographer’s head while showcasing a wealth of Cunningham’s shots the world has yet to see.

The premise of Bozek’s film proves that there’s more to the gentle man on the bicycle than meets the eye. The Times of Bill Cunningham largely draws upon a 1994 interview that Bozek conducted with the photographer. The shoot, intended for a one-minute clip to highlight Cunningham’s work upon receiving an award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), was supposed to last for ten minutes, but Bozek and Cunningham talked for nearly four hours. The Times of Bill Cunningham unearths this interview that sat in boxes in Bozek’s basement until he revisited them following Cunningham’s death in June 2016. This footage might afford the fullest portrait of Cunningham on film to date.

The interview

Bozek says that he didn’t know Cunningham much before they hit it off. The director explains that his earlier work with fashion designer Willi Smith ensured they crossed paths infrequently, but that was it. “Bill would come to our show and we’d say ‘Hello, welcome,’ and hope he’d put the picture in the Sunday Times,” recalls Bozek, speaking with POV by telephone. “That’s pretty much how I knew him.”

However, once Bozek moved on from WilliWear, he began producing segments called Fox Style News for Fox TV when the media empire was just a start-up. “I wanted to do a story about Bill and he’d already firmly refused three times saying, ‘No young fellow. I don’t want to do that kind of thing,’” says Bozek in his best Cunningham voice. “I started on one anyway, so, when we were working on stories for the next year, my crew would see Bill in the street, on his bike, or at events and they’d just whip out the camera and shoot some B-roll footage.” Once he had enough material, Bozek says he interviewed designers like Bill Blass and James Galanos, along with gossip columnist Liz Smith, for a segment on Cunningham that aired in 1993.

While Cunningham didn’t see the segment on his work, Bozek says that the photographer heard enough good word-of-mouth to pick up the phone. This time, offering another friendly “young fellow,” Cunningham invited Bozek to film the aforementioned highlight video. “I jumped at the chance,” recalls Bozek. “He had never been interviewed before.”

In his own words

This rare footage puts Cunningham’s voice at the forefront of his own story. Aside from Sarah Jessica Parker’s intermittent narration, and the occasional question posed by Bozek during the interview, Cunningham’s voice guides the film. Bozek says he structured the film in the fashion of a Cunningham self-portrait, partly to distinguish his doc from its predecessor and party to take advantage of the materials at hand. “I could’ve gotten pretty much anybody, particularly after he died, to go on camera to talk about Cunningham,” says Bozek, “but I didn’t feel we needed to because he was beloved already. I wanted to tell the story through his words, with me talking to him, and his pictures.”

The film shows Cunningham immersed in a conversation that covers his incomparable knowledge of fashion history, into which he injects stories about his life and career, including his early days as a milliner and the story about how he fell into photographing for The New York Times when he snapped a photo of a stylish woman on the street. She turned out to be Greta Garbo.

Loneliness vs. privacy

“There wasn’t a dull moment,” admits Bozek, who says the pair talked until the tapes ran out. “There were some rather emotional moments that I certainly didn’t anticipate. I was there to get a couple of soundbites about how it felt to get the award. And it just turned into so much more than that.”

The Times of Bill Cunningham sees the photographer tear up and break down when Bozek asked about the hardest times of his career. Cunningham becomes disarmingly vulnerable as he weeps for friends he lost to AIDS. Moments such as this one make the film remarkable in revealing new shades to a Cunningham’s story.

Seeing an unexpectedly talkative Cunningham might inspire a viewer to assume the lengthy interview a product of Cunningham’s loneliness. However, Bozek argues that was not the case. “He was definitely not lonely,” says Bozek. “I’ve asked his friends if he was and he was most certainly not lonely because he had people living all around him. They had dinner every Saturday night at some sleazy diner with Bill and usually Suzette Cimino, his best friend who lived a couple floors down.” The director adds that speaking with Cunningham’s friends and immersing himself in the photographer’s life simply emphasized Bill’s privacy, particularly as pertained to his sexuality and his family in Boston. “They knew Bill was a photographer, but that’s it,” says Bozek matter-of-factly. “They didn’t know his work as a designer. He loved his family, but the minute they’d ask what he was doing in New York, he would just change the subject.”

Creating a rapport

Bozek suspects that Cunningham’s candour during the interview stemmed from the fact that he wasn’t a fashion historian (despite some experience with Willi Smith) or a journalist chasing a story. “I really was just there for a completely different reason,” observes Bozek. “I think that’s why he felt really comfortable.”

Bozek says he based this assessment partly on the reactions that several of Cunningham’s friends had to the interview footage. The director explains that his first step with the documentary was running the images by Cunningham’s circle of friends, which included Ruben Toledo and his (now late) wife Isabel. (The former eventually provided artwork for the doc and the film is dedicated the latter.) Bozek says that Cunningham’s friends were amazed seeing their usually tight-lipped amigo open up. The 1994 interview demonstrates how a strong rapport and a comfortable conversation can prove more resourceful than an exhaustive list of questions that guide a conversation.

“I think he wanted to have the right forum because of his passion for documentation,” adds Bozek. “Being a historian, he had things he wanted to say. He did so in such depth and such diversity. That’s how I ended up finding out how he photographed the Gay Pride parade during the 1970s and never published a picture from them. That was not on my list of questions.” This revelation, as well as Cunningham’s reaction to his recent memory of the AIDS crisis, comes closer to a sense of his sexuality than previous portraits have hinted, although respecting the distance that the photographer set up between his personal and professional lives.

Art on the streets

The Pride Parade photos are some of the rare finds in Cunningham’s archive. The film draws from over 3 million unpublished photographs. Bozek says that, in some cases, Cunning simply didn’t release photos from his treasure trove for personal reasons. “In the case of the Gay Pride parade ones, he just didn’t want to ever do anything that would ever embarrass anyone,” explains Bozek. “Don’t forget, this is going back from 1970 when Gay Pride was called the ‘homosexual parade.’ It wasn’t even called the Gay Pride parade. I think he really was documenting it knowing that at some point in history, i.e. this film, that they would come out.”

While The Times of Bill Cunningham works as a fashion documentary on one level while revelling in Cunningham’s eye for beauty and sense of history, it also furthers Cunningham’s significance as a documentary photographer. “He was the first true street photographer as it relates to fashion and society,” observes Bozek. “It wasn’t just about fashion, obviously, because he shot more than that, particularly when he shot different parties. He shot the homeless people, so-called bag people, et cetera. He never looked back, though. This was my favourite thing about him. He loved what was happening right now.”

Diana Vreeland and the Met

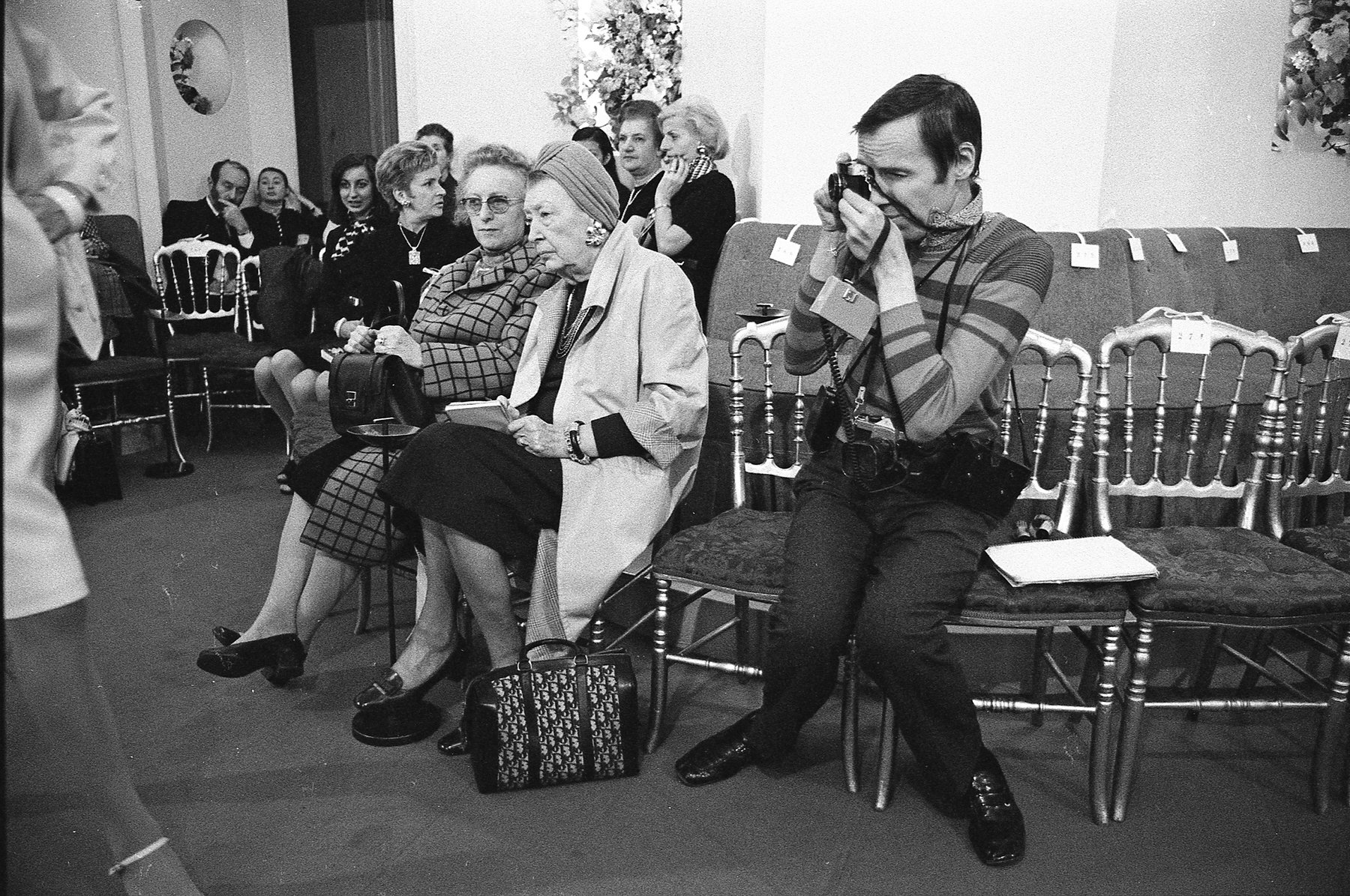

Other essential finds in The Times of Bill Cunningham are extensive photographs of Vogue editor, noted fashionista, and art connoisseur Diana Vreeland. Bozek’s film features copious photographs that Cunningham took of Vreeland while she curated exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Despite having her own documentary about her life’s work, Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel directed by daughter-in-law Lisa Immordino Vreeland, Bozek’s film shares publicly many of these images for the first time. The range of photos of Vreeland prepping her Met exhibitions is exhaustive, but only a fraction of Cunningham’s archive.

“Bill said during the interview that I interviewed that he photographed every time Diana Vreeland’s hand touched a mannequin,” says Bozek. “We’re talking two weeks times eleven years. I thought there’s no way that he did that, but then I got into the archives [years later] and I realized that literally every single time Diana Vreeland’s hand touched a mannequin, he recorded it. He captured a lot of it on tape recording too. He truly documented everything.”

Cunningham’s Archive

Despite Cunningham’s old-school analogue style—the film reminds audiences how he toured around on a bicycle and snapped photos on a consumer-grade Nikon—Bozek says that the photographer generally kept his archive well organized. The film boasts the daunting task of navigating over 3 million unpublished photographs, 25,000 of which Bozek scanned and further curated into the approximately 515 shots that appear in the film.

“The file cabinets were mislabelled in terms of some years, but you’d open them up and they were still organized,” says Bozek. The director explains that Cunningham divided everything into categories: “On the Street,” “People at Shows,” (meaning people that Cunningham photographed going into fashion shows), “Fashion Shows” (i.e. the runway shots and looks in the crowd), and “Parties.” However, Bozek says the archive housed special collections. “There were other special files, like the Pride parade and Diana Vreeland at the Met. They were big folders and you’d open one up and it would have a letter that Diana Vreeland wrote to Bill saying thank you.”

“Persnickety” Bill

Seeing all these uncovered gems further illustrates Cunningham’s private nature. Both Bill Cunningham New York and Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel had limited use of Cunningham’s work when he was alive, while the photographer’s estate gave Bozek considerable access. “He was very persnickety about who he let use pictures and there’d be one or two here and there,” says Bozek. “When he did Versailles, for example, he probably had four or five pictures in circulation since 1973 that he let other people use.”

Cunningham’s photos of an opulent party at Versailles in 1973 are a highlight of the film. Despite previous films also tackling Versailles, few works feature the range of Cunningham photography on offer here with glamour shots including Liza Minelli (shortly after her Oscar win for Cabaret), Anne Klein, and Donna Karan. “Donna saw the film last night,” says Bozek, pointing to a screening of the doc that featured Karan in attendance. “She was at Versailles—she worked for Anne Klein at the time—and in 1973 she was at Versailles and she was eight months pregnant. It’s that kind of discovery that defined the process.”

Each montage of The Times of Bill Cunningham is a discovery process of its own as viewers scan fabulous tapestries of photographs that evokes Cunningham’s iconic two-page spreads in the Times. “I wanted to do an ode to Bill,” says Bozek. “I wanted to choose every single frame of every single picture because that’s what he did every Sunday in the pages of his stories.”

Bill and Bradley Cooper

Bozek also comes to Cunningham’s story with a unique angle given that his own life inspired a character in film. The director is the basis for Bradley Cooper’s character in David O. Russell’s 2015 film Joy, which tells the story of Joy Mangano, the self-made mop maven who enjoyed a lucrative career with the Home Shopping Network, where Bozek enjoyed a lucrative period of his career beginning in the late 1990s, eventually becoming the network’s CEO. “David O. Russel and I were talking about the movie, and he asked me about how everything went for Joy, myself, and others,” says Bozek. “I knew that he was going to create a fictional scenario based on real life and that he would have to create certain things that were part of a really good story.”

Bozek says that seeing his life in this light guided his responsibility to Cunningham’s story. “As a documentarian, you have to be truthful because you can’t embellish or [take liberties] as a screenwriter,” says Bozek. The director adds that a desire to remain truthful to Cunningham’s story inspired his initial idea to approach the photographer’s friends and screen the raw interview footage for their feedback. Whereas Cunningham never saw Bill Cunningham New York and seemed to regret the exposure it brought him—a point Bozek makes in the film, which he acknowledges is contentious but maintains is supported by facts—the director has no beans about being a tidbit of Hollywood trivia. “I will never get sick and tired of people referencing the fact that Bradley Cooper played me in a movie,” laughs Bozek.

“We all get dressed for Bill”

Despite his humble and introverted nature, Bill Cunningham inspires a red carpet worthy of Bradley Cooper. The premieres for The Times of Bill Cunningham move people to toast the fashion icon by looking their best. Recent clippings feature the likes of Susanne Bartsch dressed to the nines in Cunningham’s memory. “Bill called Bartsch the Swiss Miss because she was from Switzerland,” says Bozek. “He photographed her for years. She said, ‘If I knew he was going to be somewhere, I couldn’t wear the same thing that I had worn [before].’ Her dresses were more over-the-top, but there were a lot of people who worked to get their picture in the paper, either from the evening hours or on the street. There was a whole sort of subculture of people who worked to get their picture in the paper or worried about what to wear to the Met.

“For the opening premiere, we put that on the invitation to ‘Dress for Bill,” says Bozek, citing a line that appears in one of the film’s montages. “Anna Wintour once famously said, ‘We all get dressed for Bill.’ Now many wonder if there will ever be anyone like Bill Cunningham to dress for again.”

The Times of Bill Cunningham opens in Toronto on Feb. 28 at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema.