“I had just moved to Chengdu to go skateboarding,” recalls The Last Year of Darkness director Ben Mullinkosson. “I had just done a commercial and I was kind of burned out. I was escaping L.A. and decided to go skating with my friends in China.

Mullinkosson, speaking with POV by Zoom ahead of the MUBI release of The Last Year of Darkness, pays tribute to the friends and community that helped boost his spirits. The innovative and poetically revitalizing documentary whisks audiences to the club scene in Chengdu, China, and invites them to the party at the gang’s favourite hangout, Funky Town. There, audiences can meet Yihao, a vivacious and slightly out of control drag performer who turns heads on and off the stage with killer looks and rambunctious partying. The cast, drawn from Mullinkosson’s friends in Chengdu, includes Russian DJ Gennady (Gena for short), who is on a journey of self-discovery in a new land while exploring facets of his sexuality. Meanwhile, Chengdu’s nightlife pulses with the techno beats that the DJ Darkle drops, setting the rhythm on the dance floor that affords release to friends like 647 and Kimberly. These two partiers reveal troubled pasts and share mental health issues that illuminate the sense of community the gang finds on the scene.

The director shares that The Last Year of Darkness evolved somewhat randomly after his first feature Don’t Be a Dick About It—mostly through the chance encounter meeting Yihao outside a club while sipping on local plum wine. Once the drag queen asked when the fancy L.A. director was going to make a movie about her, Mullinkosson says the project came about naturally. But Mullinkosson admits that his process embraces the elements of self-awareness and performance from which documentaries sometimes shy away. One reality is that these friends, whether at the bars or roaming the streets at night, always have something of an act. The film captures a universal truth with its exploration of the ways in which we find ourselves, particularly during the phase of adulthood when one realizes that the party can’t rage on forever. But their love for the nightlife and the bubble of their safe community becomes threatened by the changing cityscape as China modernizes and spaces like Funky Town make room for condos.

Shot with an eye for the neon lights that pop on the scene, and with a sense that the grit and the vomit on the streets of Chengdu are essential elements of the euphoria the friends find, The Last Year of Darkness creates an immersive portrait of a space, albeit a fleeting one, that the club kids can call their own. POV spoke with Mullinkosson about making a doc that’s the life of the party, empowering his friends through the camera, and navigating his experience as an American artist who is most at home in this corner of China.

POV: Pat Mullen

BM: Ben Mullinkosson

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: You previously released the short film Double Sexy about the club kids of Chengdu. I understand it was always a “taster” for this film. What inspired you to cut and release two films?

BM: Double Sexy was the short for Nowness. That came out first and that was a total of 10 days of shooting. After the first or second day, I turned to Sol [Ye], the producer, and I was like, “This is a feature. This isn’t a short: We have to keep going.” We knew immediately that we wanted to do a bigger project. Double Sexy was really helpful because [The Last Year of Darkness] was my second feature, and Double Sexy was the proof of concept short film that people could look at and see what the world’s like. It helped us get financing and to bring on other partners in production and in post to execute the full length.

POV: Was there any feedback from the short that inspired your approach to Last Year of Darkness?

BM: We would just film different friends from Funky Town and the greater underground party community going out. We’d meet up at 10:00 PM and then we’d film [them] doing makeup or getting ready, and then we would film everyone partying and falling in love–and fighting, or throwing up, or having epiphanies about why we exist, and then film them going to bed. Production was really fun. We were drinking and shooting at the same time for a couple of years.

POV: How long did you shoot for?

BM: We shot 125 days. The amount of time was five years by the end, and we had 600 hours of footage. As we were developing the story, we started filming more during daytime. It became apparent that night is this magical time where we can be whoever we want to be and escape. It’s the high, but then you go back to reality during the day and we have all these problems that we have to face. We did a screening in Chengdu recently where all the protagonists had a Q and A with the greater community of Funky Town. Everyone was like, “Man, 2018 was the golden era of Funky Town. That was a special time.”

POV: How do you juggle the roles of friend and filmmaker? Was it different if you are all out and the camera’s on, or was it all the same?

BM: It didn’t feel that difficult because we’re partying too while we’re filming, so filming was really fun at first. The main thing was the collaboration. I didn’t want to use any material that my friends were not comfortable with. We would meet up at Darkle’s house and watch [the footage] and we would talk about maybe this scene is not what we want to use, so we would remove it, or we would have conversations that were more abstract, like, “Is this the story that I want to tell?” For different characters, we would then rewrite scenes to go film. Everybody has a different level [of construction], like 647’s story is very constructed based off the narrative that he and our team wanted to tell. We all wrote his story. But then Yihao is this amazing creature: You start rolling and then Yihao is performing to the camera. He’s very aware of his presence and his beautiful talent. We just had to show up and then amazing things would happen with Yihao. Everybody had a different approach.

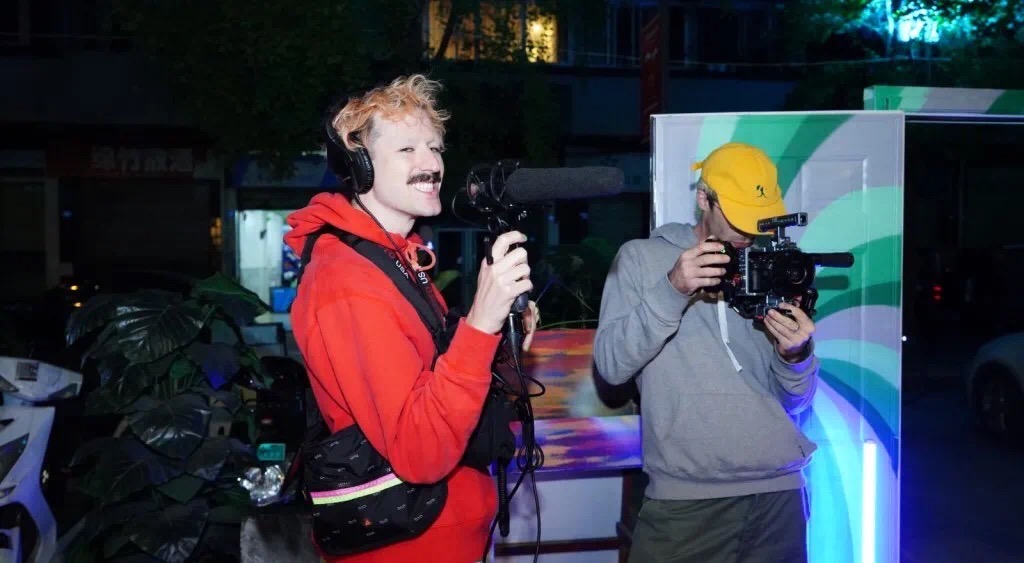

POV: I understand that Gena was one of the cinematographers. What was that process like where you have someone on both sides of the camera?

BM: We had two cinematographers, and the first cinematographer is Fei. She and I worked together in commercials in Shanghai: we do a lot of bad phone commercials for money. [Laughs.] She’s an extremely professional, knowledgeable cinematographer. When we were shooting this film, we found that the best material started to come when Gena was shooting, because Gena is friends with everyone. He took a bigger role filming, and then Fei would teach him what would look good in terms of framing, moving the camera, or having a character go out of frame and come back in. She created the vision, but then Gena did most of the execution just because he’s friends with everyone, and everyone feels comfortable, like, vomiting in front of him more so than Fei. [Laughs.] Fei’s coming from the highbrow commercial technical side of things.

POV: Speaking of the vomit, there’s a scene great scene where a girl is outside the club and is, like, puking discreetly into a solo cup. Is that footage that someone actually was like, “Oh yeah, you can use that”?

BM: [Laughs.] Yeah. She’s our friend. She’s seen me in the same conditions! We’ve all…

POV: We’ve all been there. [Laughs.] There’s another great moment late in the film, too, when Yihao tells you that he feels the documentary can’t quite capture a record of his life and that you need to “feel it.” What was it like hearing that?

BM: He’s right: we can’t. We heard that and were like, “Let’s put this in. Let’s remind the audience at 80 minutes that this is a film and we’re creating a story for them to see.” It’s not necessarily real to life because you can’t capture that, anyway. I firmly believe that anytime we’re filming, everyone on camera is presenting a version of themselves that they want to see or not. It’s still a version of you. I think it’s important to recognize that we’re making a movie. We’re not spying with a telephoto lens from really far away. It’s not like a nature documentary, but maybe that’s fake, too—that’s probably a collaboration with the zebras.

POV: Oh, the zebras are performing, for sure. But there’s another view in that we get a sense that Funky Town is changing, but the club’s closure isn’t really at the forefront of the film. It’s in the background until the end when it gets demolished. How did you decide where to put the closure of the club in terms of the background/foreground?

BM: We had many versions of the film. We had Funky Town close early on, and we had it at the ending. It took different shapes [depending] where it was placed, but, ultimately, Chengdu isn’t the same without Funky Town, so we had it go at the end. The problem with Funky Town closing is that it feels so sad. I wanted this film to end on a happier note because everyone is not sad all the time, by any means. Everyone lives really great lives and, to me, this film is a celebration of life. It’s a celebration of my friends’ experiences in Chengdu and the strength in vulnerability that they have for being so brave and being so bare by showing the struggles they go through.

We wanted it to still feel happy and positive, and I think Yihao presented that when he chose “Life on Mars” to perform in drag. In the end, Funky town still closed down; it’s like not there anymore. That’s a truth, but the techno music still lives within us. The party. Funky Town lives on when everyone’s listening to techno on the subway [at the end of the film]. It’s says the subway’s here, but we’re still partying. We’re still alive.

POV: You really do feel that sense at the end, and you’re very much a club kid of Chengdu even though you’re from the U.S. Is the film an outsider’s perspective? An insider’s perspective? Your status as a filmmaker who’s an American expat club kid in China has an interesting fit with the mélange of characters in the film.

BM: I’m from the suburbs of Chicago. I went to film school and I still work from L.A., so I still have this connection, but Chengdu is my home. I just love Chengdu and everyone on camera and everyone who worked on the film too. I feel more at home in Chengdu than I do anywhere else. I’m not partying as much right now. I still love to party, but now I’m more on the “Wake up at 5:00 AM and go running” energy instead of the “party until 5:00 AM” energy. To me, it’s not really a film about queerness or a film about partying or a film about China. It’s just a film about my friends. These are my friends who want to be part of a film. These are my friends who feel comfortable and are able to show their highs and lows on camera. Everyone feels like a movie star at this point. My intention is to show this beautiful group of friends and this beautiful world and this beautiful community. I think a lot of people call me an outsider, but these are my friends, so… [smiles and shrugs].

POV: Have you stayed friends throughout the process? You’re all still talking?

BM: Yes. We are.

POV: That’s good to hear. But also sort of within the question of identity and influences, I read that Last Train Home was one of the films that really inspired your path as a filmmaker. What about that film made an impression on you?

BM: I love that film. I saw that film when I was in film school and I was just blown away. It felt so different from my basic 19-year-old conception of what documentaries could be. It really opened my eyes to a world that I didn’t know anything about. In a lot of ways, it made me want to go to China and explore a new thing, but I was so blown away by the filmmaking: the pacing, the way that the interviews didn’t feel like interviews, and just the patience of the storytelling. I actually met the director, Lixin Fan, and had a nerd moment where we were a part of some festival together in South Korea. I was like, “You’re one of my favorite filmmakers. You really inspired me. You’re like a hero to me.” And he’s just like, “Oh, okay, cool, let’s have a beer.” He’s very humble.