As is always the case, IDFA (International Documentary Filmfestival, Amsterdam) offered up a bounty of extraordinary documentary films. The 35th edition of this outstanding festival ran from November 9 through 20.

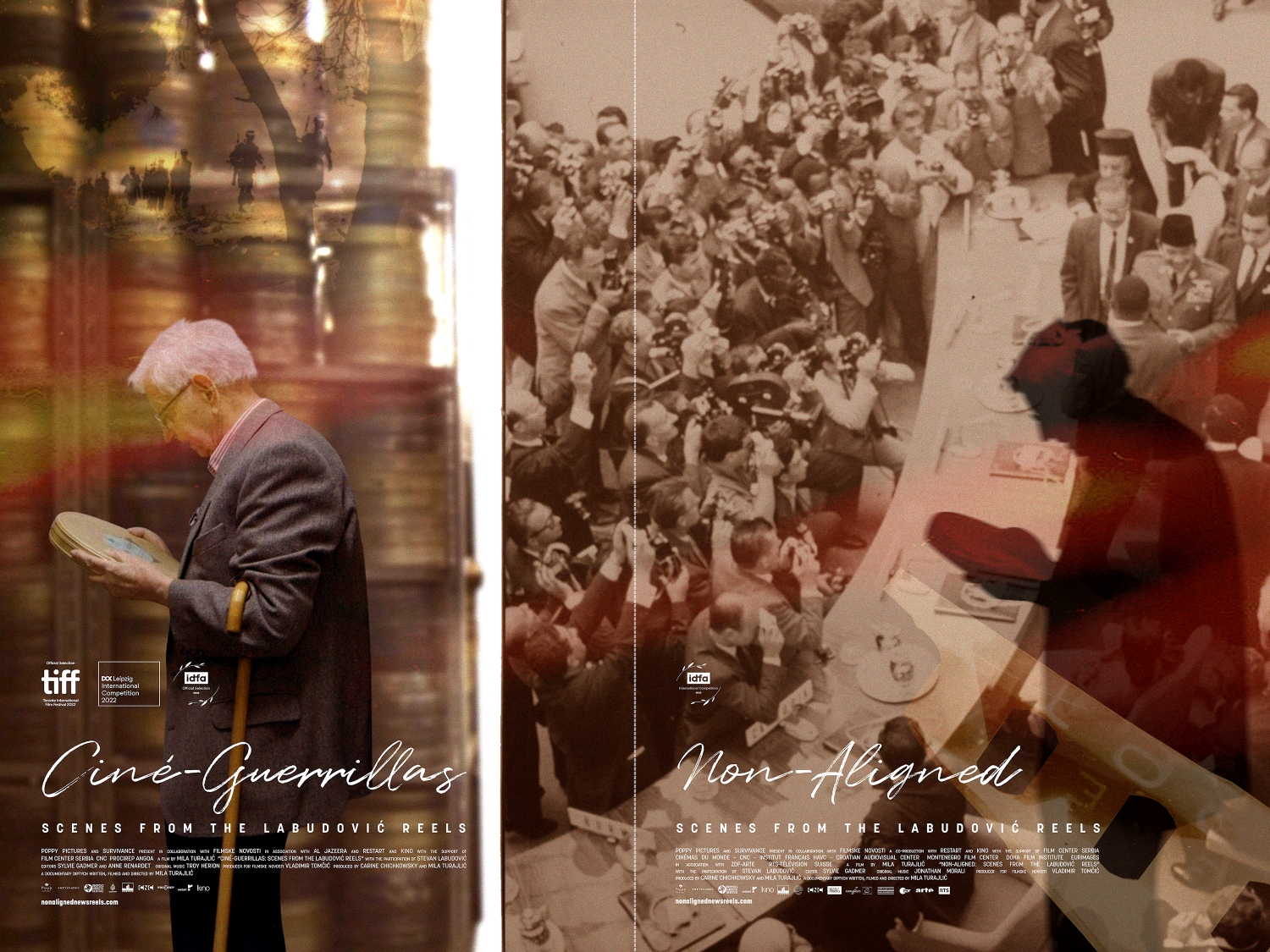

Two highlights of the Imagining Yugoslavia Pathway program were personal historical narratives: Non-Aligned: Scenes from the Labudović Reels (read more about the film in our interview with director Mila Turajlić) and The Eclipse.

The Eclipse, an innovative documentary essay that won the 2022 DOX: Award, is an astonishing debut feature by Serbian filmmaker Nataša Urban.

Bookended by the 1961 solar eclipse (embraced by Serbian people as a joyous phenomenon) and the 1999 eclipse (during which many Serbians, paranoid and exhausted by years of war, retreated indoors), this film follows the crescendo of nationalist fervour amidst the horror of armed conflict.

Grainy film interviews with the filmmaker’s family and friends about this devastating time are set to an eerie score reminiscent of William Basinski’s The Disintegration Loops. Their accounts of mass graves, sadistic “weekend warriors” and a bloody scene of a pig slaughter, are interspersed with excerpts from a mountaineering log book kept by Urban’s father. His cheerful accounts of hiking and wildlife, brought to life with contemporary footage, chillingly correspond to key dates in the 1990s’ wars. The Eclipse is a highly personal account about how we deal with the pain in the world, about what is remembered and what is obscured.

Portrait of My Father, Juan Ignacio Fernández Hoppe’s impressive second feature, is the filmmaker’s painstaking quest to solve the mystery surrounding the death of his father—found dead on a beach near Montevideo, Uruguay—when he was a child. The father’s last words were “I’m coming home late tonight.”

Hoppe sifts through his father’s last possessions, including a key, cufflinks and empty blister packs of psychotropic drugs. He probes family members on a blinding white set. And he interviews people who remember his father as a talented music therapist (and not a “disturbed” individual).

This painful inquiry, immersed in the discordant soundtrack of his father’s percussive piano compositions, tries to answer some very difficult questions. Was his father a misunderstood musical genius? Or was he an irresponsible dilettante? Why did his mother (a doctor!) refuse to agree to an autopsy?

When the research begins to stall, Hoppe questions what he is looking for exactly and he worries that he might be (accidentally) misrepresenting the father he never knew. Once you have started to dig up the past, you can’t stop half way. The dénouement is worth the wait.

Much Ado about Dying, a bittersweet British film about love, art and death, was quite popular. Called away from his documentary career in India, filmmaker Simon Chambers rushes to his uncle’s bedside after he gets a call saying, “I think I might be dying.”

Uncle David, a former actor, is actually dying from boredom and a lack of performance opportunities and is not suffering from any life-threatening disease but he is as helpless as a small child. Chambers moves into his uncle’s decrepit and unhygienic flat and starts to help out.

Much Ado about Dying is a tender portrait of a challenging uncle/nephew relationship over four years, which highlights how complicated it is to provide assistance to a fellow adult. As in Shakespearean plays, tragedy and humour are never far apart (though David does not seem to appreciate that some of his “funny” moments are actually tragic).

The most appealing part of the film is Chambers’ humble and disarmingly frank personal narration. While Chambers genuinely cares for his uncle, he does not hesitate to expound on how demanding it is to be a caregiver (especially when his assistance is not appreciated!) and how strange it is to suddenly have a massive responsibility that he never asked for. David and Simon are both artists and single gay men, who have suffered loneliness as the price for total freedom, yet they are fundamentally very different people.

Much Ado about Dying reminds us that end-of-life caregiving is a rare gift. Not everyone will be as fortunate as Uncle David. While tending to his elderly uncle, Chambers is clearly pondering his own death. Who will be there for him when the time comes?

There seem to be hundreds of documentaries about the horror of domestic abuse and violence against women. Look What You Made Me Do, accomplished Dutch filmmaker Coco Schrijber’s bold new film, is about women who decide to permanently end the abuse by murdering their abusers. The three protagonists of this film were all driven to kill before they were murderously attacked. “It’s a question of you or them.”

Schrijber’s deep bond of trust with her subjects is keenly felt in every scene. While describing their relationships, the murders or the aftermath, all of the “perpetrators” reveal a wide range of emotional states in heartbreaking detail. The nervous strident score, spliced with corny love songs, reflects these women’s toxic and disorienting experiences. Remarkably, 16th century Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi makes a cameo appearance via an ancient court case and the painting of a violent biblical scene.

Casual commentary about their daily work from cleaners in biohazard suits who are busy wiping away stains in a beautiful home is a stark reminder that domestic violence is commonplace. Every year, 30,000 women are killed by their partners worldwide. Three subjects in Look What You Made Me Do refused this fate.

Russian Alexander Abaturov’s observational film Paradise, set at the frontline of a deadly forest fire in northeast Siberia, deals with humanity’s greatest existential threat, climate change. As the inferno, fed by high winds, rips through a forest parched by an unnaturally dry summer, the inhabitants of Shologon, a local village imperiled by the fire, begin to refer to it as a dragon. The villagers view it as something wild, something alive, because it won’t allow itself to be caught.

Then, while the sky turns orange and Shologon begins to fill with smoke, the villagers confront another grave threat, the indifference of the Russian federal government.

Shologon is located within a so-called Control Zone, an area in which the authorities are not obliged to fight wildfires if the cost of extinguishing them exceeds the estimated damage. Although the villagers have some access to modern technology (they can see the fire approaching via drone images) they do not have professional tools or training to fight the fire. Paul Guilhaume’s magnificent cinematography captures both scenes of apocalyptic destruction and the villagers’ formidable efforts to stop the fire.

Paradise is a grim reminder that as global warming intensifies, many more vulnerable populations will be left to their own devices to protect themselves. The villagers of Shologon do everything in their power to fight the wildfire. What happens when “everything” is not enough?

IDFA featured quite a number of fascinating arts documentaries including Art Talent Show and Cosmic Chant. For example, Karlovy Vary prizewinner Art Talent Show is a highly entertaining observational film about the annual evaluation process at the Prague Academy of Arts. This film, inspired by Claire Simon’s Le Concours, provides a fly-on-the wall view of the evaluation in three of the academy’s studios: New Media, Graphic Design and Painting. After the teachers have divided the students’ submitted works into either pretentious statements or Art with a capital A, their complex and often grueling, “friendly interrogations” begin.

The film, shot over one week, is primarily focused on the studio talent tests. The prospective students paint, scream (on command) and answer confrontational questions. Art Talent Show shows the toll that this process takes on all involved. Interspersed between moments of playful camaraderie, the teachers clearly suffer through the exam process too.

Bad art is easy to recognize. Art Talent Show asks, ‘What is the role of art in our current society? How about an arts academy?’ Through it all, the academy receptionist sits calmly in her booth, a foil for the madness and the drama around her.

Cosmic Chant, awarded best documentary feature at Guadalajara, is a stylish profile of avant-garde Spanish performer Francisco Contreras Molina, aka El Niño de Elche. This former Boy Wonder raised with flamenco at his father’s knee, is actively pushing the limits of this quintessential Spanish music. From a primal rendition of flamenco featuring only voice and a mallet to psychedelic music videos, Cosmic Chant explores what makes El Niño tick. Flamenco is in his blood. Every musical genre he experiments with turns into flamenco. But how far can you push a musical genre before you extinguish it? Not everyone appreciates El Niño’s experiments.

By turns intellectual, daring and sentimental—this middle-aged provocateur is clearly very close to his parents— El Niño is in a permanent state of exploration. His brand is essentially no brand at all.

The New Greatness Case, an alarming real-life thriller about state repression, is narrated by Russian filmmaker Anna Shishova-Bogoliubova, who grew up hearing about Stalinist-era purges. In 2018, 17-year-old Anya, along with nine other young people, was arrested on suspicion of forming an extremist group. This friendly teen believed that she had joined a group of like-minded online peers who hoped for a brighter future. As far as Russian authorities were concerned, Anya and her peers were planning to overthrow the government. During the course of this Kafkaesque tale, Anya and her family discover exactly how far the Russian state is willing to go to suppress dissenting opinion.

Dreaming Arizona, a documentary fantasy played by real people, is the latest offering from Danish director Jon Bang Carlsen. This documentary hybrid in Carlsen’s signature style follows five young people who are growing up in a remote town in the American Southwest. These teenagers desperately want to feel hopeful and hold onto their dreams, but toxic domestic situations and lack of support threaten to keep them stuck in a rut, replicating their parents’ lives. Through dreamlike sequences that may or may not be real Carlsen provides alternative futures. To make something happen, first you have to dream it.