Hot Docs celebrated its three decades as a nonfiction media force with its first fully in-person edition since 2019, delivering its triple-barrelled blend of films, the funding Forum and the Conference. The latter attracted some of the leading lights in the industry for a series of scintillating conversations.

“EDI: What’s the ETA?”

One of the more hotly anticipated sessions at the Conference, “EDI: What’s the ETA?,” addressed head-on one of the predominant sociocultural themes of the 2020s–EDI: equity, diversity and inclusion–that has driven not only the documentary ecosystem, but also a myriad of sectors, public and private, in Canada, the US and around the world.

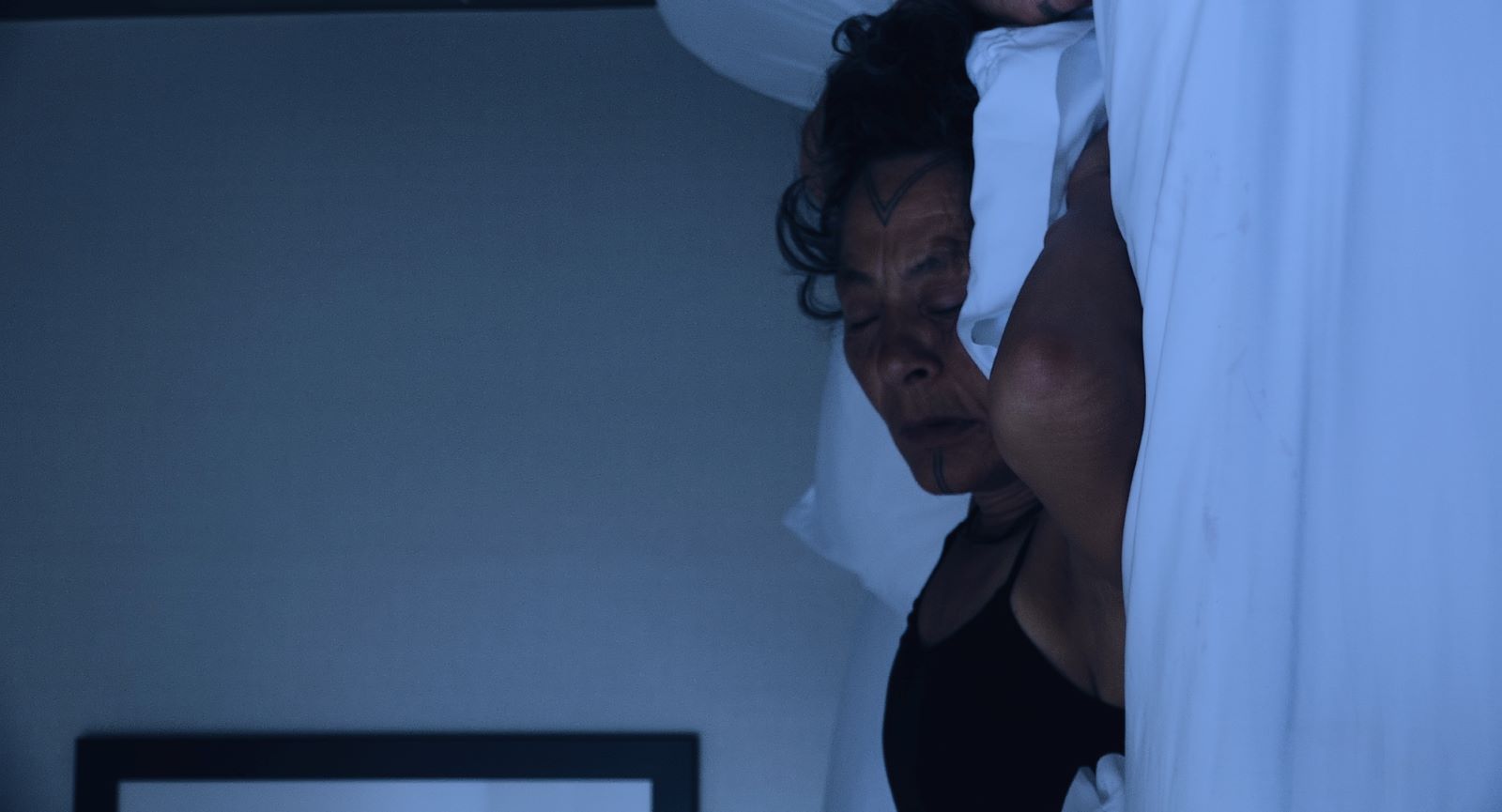

Malikkah Rollins, Director of Industry and Education at DOC NYC, moderated the hour-long conversation, which also included Nataleah Hunter-Young, International Programmer, Africa and Arab West Asia at Toronto International Film Festival; and Milisuthando Bongela, director of Hot Docs World Showcase film Milisuthando, who Zoomed in from her home in South Africa. The participants grappled with where we are now, and where we need to be.

“This isn’t just a problem in the documentary space but in the film industry generally, and in particular, in Europe and North America,” Hunter-Young maintained. “It’s an ongoing struggle to ensure that [filmmakers] can travel with the work that they create.”

Hunter-Young also cited the challenges among makers from the Global South to secure funding. “It’s not uncommon for a lot of the films that I program to end up coming through Belgium or France or Italy, just to get the funding necessary to compete on an international stage. That’s not so much an independent problem of the country as it is an ongoing problem of the colonization of those spaces; it’s continued to be mediated through these European funding bodies that do their best to try and shape the visions of places around the world, particularly on the African continent.

“If an African filmmaker is looking to make a documentary about rape or violence or any of those kind of stereotypical issues,” Hunter-Young continued, “an NGO will be right there ready to fund that. But when it comes to a story that they feel is important for their own reasons, there are typically all sorts of barriers that they have to cross in order to prove the worthiness of that story.”

Bongela noted the cultural make-up of the session itself: all Black women. “It’s wonderful that we have the platform to engage these questions, but I think if we’re going to be talking about equity, diversity, and inclusion, the table that we’re sitting at right now has to reflect that. It’s always the people who are not in these positions of power that have to come together to figure out how to resolve these things.”

Bongela suggested that institutions need to fully integrate those in power into the process of engaging EDI issues, transforming them into intrinsic, foundational elements, rather than perfunctory box-checking exercises.

Rollins concurred with Bongela, citing the Forum that was happening at the same time, driven by “some really powerful people who have access to money and platforms…Why are they not here with us? Why are we not all together having this conversation?”

She went on to ask, “To what extent is the industry still doing performative EDI work versus authentic EDI work? And what does it look like? To what extent are they actually doing the deep, deep work of change, within their organizations? Martin Luther King Jr. said all meaningful and lasting change begins on the inside.”

“For me, this work requires dialogic encounters,” Bongela maintained. “It requires us to figure out, ‘What does it mean to sit across from each other, and use our differences as a way to imagine a new world?’ These changes happen when we are with each other in the same room, engaging in our discomfort, and engaging in vulnerability.”

“For a lot of folks,” Rollins concluded, “it’s something that should be in the DNA of who we are, in the DNA of our organization; we shouldn’t have EDI departments. What we are fighting for right now is freedom. And my freedom doesn’t take anything away from you.”

“Made in Ukraine”

Freedom has certainly figured in the hopes and aspirations of Ukrainians over the past year, and the Hot Docs programming team responded with the “Made in Ukraine” strand of features and shorts, as well as the session that complemented it. Ukrainian producer Anna Palenchuk moderated the session, which featured filmmakers Roman Liubyi (Iron Butterflies) and Mila Teshaieva (When Spring Came to Bucha).

When Spring Came to Bucha captures life in the aftermath of an unrelenting Russian attack on the Ukrainian city of Bucha and the subsequent withdrawal of troops. “None of us expected to see what we saw in those first days of Bucha,” Teshaieva recalled. “And basically, there was no preparation, no plans. I started filming because I felt it was my duty as a witness to record.”

Iron Butterflies is an investigative piece that traces the 2014 downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 over Ukraine by Russian forces, and argues how the lack of judicial consequences for this action led to the Russian invasion. “You can’t make these people accountable because they hide in Russia,” Liubyi noted. “But the fact that the film exists, and tells what happened there, it’s already bringing a little bit of justice in the world.”

Palenchuk asked both filmmakers about ethical concerns in making their work.

“I captured not only Russian war crimes, but also how to get back to life after a disaster,” said Teshaieva. “So my focus in this film was to go from this point, when it seems that life is not possible anymore, and follow people who are handling the situation somehow.”

“I’m just telling how I saw the situation, how I see the connection between downing the passenger plane and full-scale invasion,” Liubyi explained about his film. “I can’t lie to myself or to my audience. [Mila’s film] is a type of documentary where [filmmakers] have to establish connections with characters. I’m mostly avoiding those types of films. I’m working with archives and mostly in the editing room because I don’t want to harm characters. I don’t want to shoot my film and then forget about that person.”

“I hope that both of our films arise…[from] very deep philosophical questions about human nature,” Teshaieva maintained.

As for their next projects, Teshaieva intends to return to Bucha and pick up where she left off, documenting the consequences of war and the flickers of hopes and expectations that inform the rebuilding and reclamation processes. Liubyi is working on an animation project, aimed at Ukrainian kids, as an antidote to life during wartime.

Palenchuk then introduced several Ukrainian filmmakers in the audience who had relocated to Canada, and asked them about the most pressing needs of the Ukraine doc-making community. Predictably, time and money are the biggest challenges, especially with the Ukrainian government redirecting resources from culture to the military.

One audience member namechecked Babylon 13, the filmmaking collective that was formed during the 2014 Maidan uprising, as a statement of resilience and action. “We started working harder because we understood that the only way that we could make a film was by actually doing it ourselves,” she explained. “Not to look for any support because it also takes a lot of time and energy.” The Babylon 13 YouTube channel showcases 300 shorts, as well as Iron Butterflies.

“Ukrainian filmmakers are really blessed,” the audience member continued. “We have each other and I feel that the major thing I need is for my people to be on my side. When we’re together with the people who have similar ideas and values, you can do almost anything.”

“Distribution Gurus”

The ever-grinding quest for optimal distribution scenarios remains both ever-evolving and evergreen. The “Distribution Gurus” session gathered together mavens from both sides of the Canada-US border to proffer wisdom and advice. Moderator/Hot Docs Industry Coordinator Winnie Wang shepherded filmmaker/author/strategist Jon Reiss; Gathr CEO Scott Glosserman; and Rachel Gordon, author of The Documentary Distribution Toolkit through an hour-long rumination on streaming, educational distribution and non-theatrical events.

“It’s how your audience engages with you online and how they engage with you to find out about your film,” Reiss asserted. “That’s key and fundamental. And from that you’ll find many different avenues, besides just streaming. The problem with streaming is that you’re relying on other people to accept your content. You have to understand what your film is, what your audience is, and not be beholden to a gatekeeper.” He also pointed out that the big streamers aren’t as receptive to political content as they used to be.

Glosserman advised to be cautious about streamer deals, which could tie up your rights for many years. “There’s still an iterative process to distribution, where you galvanize your community. You have top-down or bottom-up theatrical, followed by a transactional VOD window and SVOD. Streamers can be very enticing, but there’s not a tremendous amount of upside beyond what you might get for streaming.”

When she was writing her book, Gordon found that most film schools were not strong in teaching the business side of the doc ecosystem, especially about retaining long-tail educational distribution rights. “Always make sure that you have a lawyer look at a contract and feel like you can negotiate,” she recommended. “A lot of filmmakers don’t understand that they don’t just have to take the first thing that falls in front of them.” Reiss added, “And when you’re asking people for advice on companies, ask a recent person to see how they’re dealing with people now. And ask someone who’s been there for a few years to see if they’re getting paid.”

Reiss was keen on live events, having advised several projects that had not secured distribution, but had found audiences anyway through this pathway. “Make sure that you carve out certain things such as direct distribution, the ability to directly sell your public performance rights, because live events will continue to always be a way for you to monetize and drive impact through your film.”

“You really need to lean into live in-person events to be able to drive engagement, measure engagement, and drive revenue to the extent that they can,” Glosserman asserted. “You need to find the right technology and the right models in order to exploit those different opportunities.” He also suggested building a network of partner organizations early in the production process.

Wang asked the panel about festivals, particularly as they consider post-COVID scenarios such as hybrid virtual/in-person formats. Can we rely on them as platforms and marketplaces?

Travel to festivals is prohibitive for many filmmakers, and not all festivals pay screening fees. Reiss emphasized that festivals are gatekeepers, and stuck with his credo: “Don’t be beholden to gatekeepers.” He has consulted on docs that aren’t necessarily festival films, but with a well-considered strategy, he was able to help his clients find their audiences.

Glosserman wasn’t as dismissive; he advised to “distinguish the ‘buyer’s market’ festivals from the cultural festivals. If you premiere at the right ‘buyer’s market’ festival, get a perception of value, regardless of a sale, (and) you get a really great response, you could then play your film in 60 festivals and make $350 a screen. I would think about film festivals as another distribution window.”

Wang steered the conversation to the short form, which the panelists agreed was a vital tool for community engagement; what’s more, the platforms for shorts–i.e, Field of Vision, New York Times OpDocs, POV Shorts, et al–continue to grow, albeit without a corresponding rise in remuneration.

Rounding things out, an audience member asked about data analysis–a costly endeavor for indie makers, but, as Reiss mused, “[it] would be great if film organizations and funders opened up a data-set channel for independent filmmakers. Maybe that would be an interesting initiative for that organization to buy into a dataset, and then do a data grant to filmmakers, just like they do funding grants.”

In this troubling landscape of acquisitions, consolidations, layoffs, and cuts, distribution ought to be engaged as both an art and a science, with an open mind, an open heart and an irrepressible spirit.