“In a real tragedy, it is not the hero who perishes; it is the chorus.” — Joseph Brodsky

On May 29, 1985, in the final of the annual tournament to decide Europe’s best football team, reigning champions, Liverpool, met Juventus of Turin at Heysel Stadium in Brussels. Thousands travelled to watch their heroes play. Kick-off was postponed after Liverpool fans broke a fence, then invaded and attacked a section of Juve supporters in Block Z of the stadium. The resulting panic killed 39 people, almost all Italian. Nevertheless, the match proceeded, while dead and injured were hauled to hospitals. At half time, over tinny music, the PA system announced names of the missing.

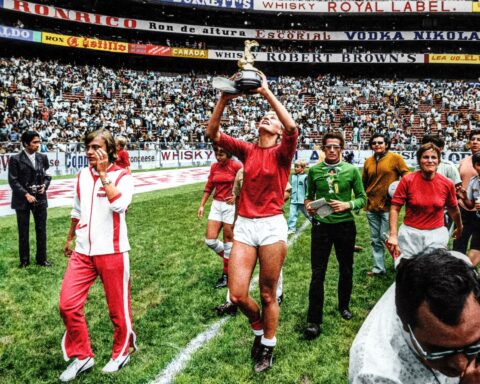

Juventus won with an undeserved penalty goal, awarded by an undoubtedly intimidated referee who understood that justice could only be served by Liverpool’s defeat. Liverpool, perhaps too shamed by their fans, did not score, though any efforts were hampered by further decisions from the referee, who found himself meting out a larger burden of justice than the FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association) rulebook prescribed.

In commemoration after 20 years, the documentary Heysel: Requiem for a Cup Final pores over the evening’s events. The bleeding heart of the film is footage from sports cameras that became news cameras. When fans across Europe, cradling national beverages of choice, settled in front of their televisions to watch the match live, they did not see champion footballers strutting out to greet adoring crowds. Instead, they were confronted by the sight of people running around terraces; bodies piling on one another in indignity; youths posturing aggressively; policemen hammering stray rowdies or innocents; faces vivid with fear, distress, and hatred. Before 9/11, the Heysel Stadium tragedy was the first time nations witnessed, in the comfort of their homes, a distant accumulation of death as it happened.

Heysel: Requiem for a Cup Final struggles between requiem and inquest. As a requiem, it follows stories of mourning. In her picturesque Italian town, Beatrice Martelli watched the mayhem on her TV, anxiously waiting to hear from her son, Franco, until his friends called to tell her of his death. Three cousins, Danilo and Armando Ragazzi and Guido Corini, were separated in the thronging hysteria from another cousin, Domenico. Eventually, they found him in a Red Cross tent, one in layers of corpses. Martine Bollu, a fire-station social worker called to duty at Heysel, reads from a haunting, thoughtful diary of the night, written to pacify her sorrow. Two affluent couples, Alessandro and Titziana Antonini, and Fausto and Antonella Moschino, describe how Titziana was separated from them. The men searched Brussels hospitals; she lay in one in a coma. They recall “a sea of desperate people” and rows of bodies in a morgue.

Also, in the theme of requiem, the sole Liverpool fan in the film, Terry Wilson, expiates his culpability. He served nine months in prison as one of 14 English fans charged with manslaughter. Now, as a born-again Christian reading hand-wringing Biblical texts to schoolchildren, he claims to regret his actions of that night in Block Z. Yet he describes those actions as a chivalrous attempt to rescue a Liverpool boy being attacked by Juve fans.

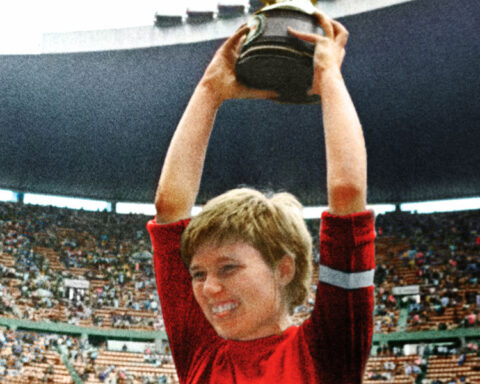

Those ten participants account for the requiem. Fifteen others perform an inquest. Liverpool and Juve team members, officials, politicians, bureaucrats, and police officers describe what the narration calls the “combination of factors” responsible for the deaths. They finger shoddy policing, placing Juve and Liverpool fans in adjacent terraces, and the poor state of the stadium with flimsy fencing and rubble laying scattered as potential missiles. Then they relate the tense debate about whether the match should proceed.

Had Heysel: Requiem for a Cup Final remained a requiem, it would be a touching memorial. But the bulk of the participants and content form an analysis that is resolutely incomplete. The film fails to mention what the tragedy was about—football violence. A tribal ire among Liverpool and Juve fans caused the deaths; fear of further violence led to the decision to play the match.

As the film shows, among all the European channels with feeds from Heysel, only the Germans, having taught the world a thing or two about violence, refused to broadcast the match. They announced, with shuddering recognition, that the point of continuing was “not to play the European Cup Final, but to prevent further mass hysteria”

The Heysel tragedy was, to date, the most public display of the culture of football violence. Terry Wilson hints at that culture. He says in disbelief of his arrest, “All I did was run over, throw a few fists—and—manslaughter?” For him, throwing a few fists was a routine pursuit. The film subtly probes what players on both teams knew of the deaths. One must infer that the riot itself did not warrant abandoning the match. Three weeks before, fans had rioted at Birmingham City’s ground. The same night, a fire at Bradford City’s stadium killed 56; there was no violence, a wooden stand’s poor condition made it kindling. May, 1985, was already a wretched month for English football before Heysel.

Heysel resulted in English teams being banned from Europe for five years, Liverpool for six. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s advisers delicately dissuaded her from forcing matches to be played in empty stadia. The English shouldered the blame for Heysel, football hooliganism being “the English disease.”

Less well-known is that the year before, when Liverpool won the European Cup against Rome, in Rome, ordinary Liverpool supporters, including families, were hunted down in knife attacks by scooter gangs. One thirteen year-old boy needed 200 stitches in his face. Also in 1984, Juve fans in their Turin stadium hurled stones, flagpoles, and bottles at Manchester United fans in a terrace beneath them. Heysel was scheduled for reprisals. A unified force of fans from different clubs, including a contingent of the fascist National Front, travelled to Brussels. There were Italian fascists too among the Juventus supporters, goading intrusions into the centre of Liverpool support.

In Heysel, the Juve tribal fans, the“Ultras,” evidently foster violence: masked, brandishing sticks, beating uplone Liverpool supporters. Juve’s goalkeeper, Stefano Tacconi, describes going out with his teammates to try and quell them: “When you’re in the middle of a mob, even if they’re your own fans, you don’t feel that safe.” The impression we gain is that this was a spontaneous, unusual mob.

Heysel: Requiem for a Cup Final avoids saying that the eruption of a widespread, barbaric cult caused the tragedy. At the end of the film, Terry Wilson reflects that he has learned of life that “It’s not about being one of the lads.” We are not told what “being one of the lads” means.

At that time, football was still a game of the working classes, the less fashionable ones at that. As is evident from the bouffants and mullets of the Liverpool players in the film, footballers had yet to achieve the trend-setting glamour of David Beckham. The game’s gentrification would not begin until the’90s. In the ’80s, much of the discussion, led by an elite, about what was “wrong” with English footie and its apparently inherent crowd violence centred on assumptions about the frustrations or degeneracy of the underclass. Yet many of the most avid members of the highly organised “firms” that travelled the country following their teams, systematically thrill-seeking savage fights with opposing “firms,” were well-off, independent tradesmen, the working-class gentry.

he key book on the subject (there is no equivalently substantial drama or documentary) is Bill Buford’s searching, witty, and chilling Among the Thugs. He enters the world of the firms and, while keeping within the bounds of the law himself, experiences the transcendent ecstasy of shedding the self and uniting with others in a willful, orgiastic transgression of social boundaries: throwing a few fists, kicking a few heads in, mixing it.

The bonding heat of the firms was on the terraces. Until the ’90s, cheapest tickets at stadiums packed fans together—standing on long, wide, banked, cement steps that often reached high into the stands. Among the most notorious was the Stretford End at Manchester United’s Old Trafford. I stood there just behind the goal with two or three other school girlfriends for 1971-’72 and ’72-’73 homematches. When the ball reached our end, thousands would surge forward, squeeze and carry you, then flood backwards again as the ball moved up field, sweeping you in waves and eddies to catch sight of the play. It was a breathtaking fun fair ride structured with flesh and bone. Occasionally, with a small stumble, I’d realise how close we were to a cascading collapse of bodies: if a knot of people fell over, if a tossed firecracker landed among us, or, as happened at Heysel, if opposing fans infiltrated for a fight.

Football organisers often treated crowds with contempt, herding them into caged pens with no facilities. No wonder fans responded contemptuously. So why was I in the Stretford End, one such pen? Because it was cheap, and it was fun, in a tightly knit crowd, to join chants devised and spread with the unity and speed of a flock of birds changing direction. It was also consolation, as Manchester United plummeted down the league with a trajectory felt in the pit of our stomachs. All we had to cheer was ourselves—“loyal supporters!”

The Stretford Enders included some of the nastiest, most skillful operators in the competitive field of football violence. I’d see them outside the ground, shoving opposing fans, saving the heavy stuff for the formation of a critical mass of fellow tribesman at a place away from police and outsiders. As a female, I was treated with friendly respect. A brewing fight might be interrupted with the greeting “you all right there, love?,” the thug looking out for me. I met similar deference a few years later at the huge, pulsating, gay nightclub, Heaven, in London. One night, I ventured into the Ladies and, hearing athletic sexual activity from an open stall, cleared my throat as an alert. I heard, “I think there are ladies in tonight.” After a shuffling intermission of clothing regathered, two men exited, one politely asking, “you all right there, love?” Two male cultures, one cruel, one benign, but both exclusive, and defined by carnal objectives.

Terry Wilson is caught on film in Heysel at the Cup Final. He is in Block Z, thrashing his arms, baying like a Berserker. One of Bill Buford’s more affable thugs explains, “What it does is this: it gives violence a purpose…. because we’re not doing it for ourselves. We’re doing it for something greater—for us. The violence is for the lads.” This is what Terry Wilson means about “being one of the lads.”

Attila Lukacs’s monumental paintings of men poised for violence capture such lads; they might admire his works, get them, appreciate the glorification. But were you to helpfully instruct them in the homoerotic overtones, they’d smash your face in.

Latent homoeroticism, underclass frustration, political disengagement, the decline of the Church, modern ennui, genetics: all have been touted as bases for the cult of football violence. Whatever the causes, it has given lads a sense of higher purpose and release, involving the most extreme bodily commitment, in an alcohol-saturated, brutal, and focussed sense of the now. Unfortunately, they haven’t kept it to themselves.

Football violence has declined dramatically in Britain. Four years after Heysel, a worse disaster, again involving Liverpool fans, killed 95 of them, at an English FA Cup semi-final in Hillsborough stadium, Sheffield. It was triggered not by violence, but poor crowd-control and primitive terraces. Afterwards, accumulated, informed recommendations were finally instituted—closed circuit security cameras were installed, terraces abolished in favour of seating, better segregation of opposing fans, trained stewards, efficient policing, and clear exit routes.

Nowadays, diminished firms follow teams. Instead of attending the match, they may seek out the opposition at its home pub. Opposing firms schedule confrontations by text message. For the most part, the multitude of fans who only want to go and watch a game of footie can enjoy the gentler pleasures of fandom: emotional investment without responsibility, spectacles of skill, shared misery or joy, and the wit of a crowd devising a chant. Those with strong appetites that seek harsher pleasures from a sport as thrilling as football still lurk in the crowds though, and not just in England; unfortunately violence remains a fact in every continent that loves “the beautiful game.”