Note: this article is from our Spring/Summer 2021 issue and went to print in April 2021. Numbers on the COVID-19 pandemic reflect the data at that time.

Part one: Marc’s report

This is the time of the pandemic. We’ve learned a lot recently: about Zoom, the best kind of safety masks, and how to create a social bubble. Many people have suffered the heartbreak of losing family and friends. Many, too, have lost their jobs and businesses and are barely hanging on to a semblance of the existence they had before the virus descended on us.

It’s well over a year since the spread of COVID-19 shut down the world. The statistics are grim: from January 2020 to March 29, 2021, over 2.8 million people have died of it around the world; as of press time, the number of reported cases is approaching 138 million. There have been over 31 million cases reported in the U.S.A. (#1 in the world), more than 12 million in Brazil (#2) and India (#3), and over one million in Canada (#23). Though vaccines have arrived, more cases and deaths are reported every day, variants are rampant, and there is fear that a virulent new strain could surface this summer.

We’ve all tried to respond to the pandemic in our own way, from front-line workers to the medical establishment through to politicians (ok, only some), journalists, and filmmakers. The challenge for documentarians to show responsibly what has been happening while COVID is raging. How have politicians from Bolsonaro to Modi to Merkel to Trump responded to the pandemic? Docs can show us. What happened in Wuhan, the epicentre of the crisis? Several important docs, like Hao Wu, Weixi Chen, and Anonymous’s 76 Days and Nanfu Wang’s In the Same Breath, have given us quite a variety of answers. Filmmakers worldwide are giving us personal, societal, political, and philosophical responses to COVID.

Then there’s the question of how to film in an ethical manner during these times. How can the filmmaker or photographer treat his or her subjects in a responsible fashion so that they’re not threatened by the disease? How about their colleagues? What precautions can take place to ensure their safety?

Canada is one of the great lands for documentary production. It’s disconcerting for Canadians to realise that we’re number 23 in the world in reported cases and there’s no end of stories to be made about conditions here. Many pandemic docs have been shot, are being shot, or expect to shoot in the next few months. Let’s look at some Canadian responses to COVID.

Matt Gallagher’s Dispatches from a Field Hospital

Matt Gallagher is one of the first Canadian filmmakers to respond to the COVID crisis at feature length with his Dispatches from a Field Hospital. Born in Windsor, Gallagher often makes films in his hometown despite having lived in Toronto for a couple of decades. “It’s a city of 200,000 people and it’s far enough away from Toronto that there’s a lot of really rich documentary subjects down there that don’t get covered,” he said to POV. When COVID hit, Gallagher explored the idea of filming in one of the public buildings in Windsor, which had been transformed quickly into a field hospital for long term case patients and others struck early by the pandemic. His idea of being embedded in a hospital was turned down politely but firmly due to health concerns for the patients.

Within a week, though, Gallagher’s situation shifted enormously. His aunt Virginia was diagnosed with and died of COVID while his father, Morrie, who was in the same long-term care facility as her, was moved to the field hospital where Gallagher had wanted to make his doc. “It all happened very quickly and we were just reeling from it,” he recalled. “As a family, I’m on the phone with my mom and my sisters, and we’re trying to find out about dad’s health.

“I was thinking that this field hospital is probably going to be the last time that we’d get in touch with my father. I thought, with what I’d been hearing about it in New York and around the world, that these field hospitals were basically warehouses for the dying.”

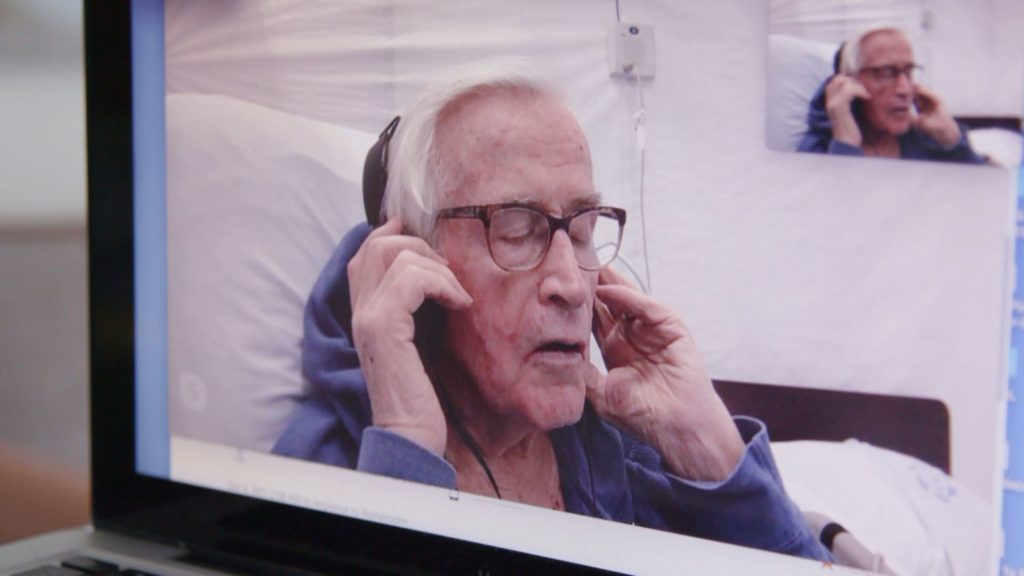

Gallagher’s mother, who is a caring figure throughout the film, remained more optimistic than her filmmaker son. “She started to say, ‘Well, Matt, he’s going to be fine, and the doctors are phoning me every day.’ Not only that, my father was mostly asymptomatic. So my mother and the medical staff are having discussions and I started to wonder about the phone calls and Skype calls and Zoom calls.

“Early in my career, I had done a lot of documentaries in military history. With stories of World War I and World War II, all we would have to tell the emotional aspects of these stories were letters from the front, dispatches from the front,” explains Gallagher. He realized that his film could “tease out an emotional journey” during COVID through modern communications technology.

TVOntario responded immediately to Gallagher’s pitch for a personal COVID doc but practical considerations had to be tackled quickly before shooting could commence. The director had to figure out how to have his mother and other old Windsor friends work with his crew to record their calls safely with loved ones. And Gallagher’s crew had to be safe, just as important an undertaking.

Gallagher recalls, “In terms of the crew and the production side of things, we bought everyone iPads and taught them how to use them. We taught them how to record a Zoom call or a Skype call. Then we stood back and let them have their discussions with their loved ones. Every couple of days, I would get these Zoom calls or Skype calls in my email.”

In the film, we see Gallagher and his team arriving at his mother’s house nearly every morning.

They would have to wait until the hospital called to let them know that a phone call from his Gallagher’s dad or doctor was on the line. “My mother, who is 81 years old now, not only had to know how to use an iPad and the Zoom or Skype call. She also had to learn to record. There are times when she would talk to my dad and get very excited, so the last thing on her mind was the technical side of things. So, sometimes footage would be lost,” he says with a shrug, knowing that what he had got was more than enough to show the beauty of his parents’ relationship.

Regarding how he shot the film with his colleagues, Gallagher recalls, “We were a small film crew that had to have protocols on how to do things and how far we could [physically] be from each other. We couldn’t travel in the same production vehicle. We all had our own vehicles and our own hotel rooms and there was no crew meeting at a pub for dinner.

“There were a few simple rules—you wore masks, kept 12 feet apart, didn’t use body mics on people and didn’t touch anybody. If I handed a piece of equipment to my sound guy, that piece of equipment was sanitized, and if he plugged in a wire to my camera, that wire was sanitized,” says Gallagher. “We were overly careful. I was dealing with my own family who was dealing with the case of our father having COVID, and I was dealing with all these other families who were suffering because they had a loved one who had COVID. The last thing that I wanted to do was to be part of the transmission of some virus.”

Gallagher says that production allotted extra time for arrivals when filming with his mother or other families. “We figured out the mics and the wires and where to put them, and made sure that everything was sanitized and hooked up to landlines. It took us about an hour every morning [with his mother], and then we would just sit around and wait for hours, often in the rain.” And, according to Gallagher, it rained a lot last spring in Windsor!

Besides footage from the families’ homes and audio from calls, Gallagher was able to shoot in the field hospital once the initial crisis had passed. “The field hospital was shut down [by August] and all the patients were out, and it was sanitized,” recalls the filmmaker. “That was the point where I was allowed to go back into the field hospital with a drone and a stabilizer and get all these very cinematic moments that I could use in the documentary.

“More importantly, it was a chance to have individual sit-downs with the field hospital staff, and I could talk about the patients that I already knew were in my film. It was a nice way to tailor the story.”

Often doc stories have nice surprises. For this film, it was the discovery of a cache of iPads, which had been “in the hands of doctors and nurses and housekeeping staff who were also filming things as they were going about their day. They were filming the moments that are things that you wouldn’t normally see.” It took time and lots of persuasion but in the end, some excellent footage was obtained that way.

“I was able to provide for the documentary a firsthand account of those days,” says Gallagher. “It didn’t look so scary after all, after seeing that footage. It didn’t look like a warehouse for the dying anymore. Quite frankly, it looked like a place that if I was sick, if I had COVID, I would say, ‘send me to that field hospital, that’s the place that I want to go.’ Because the care and the amount of resources and things they did to help people through this was incredible.”

Yung Chang’s Wuhan Wuhan

One of Yung Chang’s motivations for tackling his new film is the shocking reality of anti-Asian prejudice in North America. “My daughter and I were walking in our neighborhood in the Junction,” he recalls. “We had an encounter, which I’ve never experienced since my early childhood, growing up in Whitby. We had an anti-Chinese racist encounter with someone and it was horrifying.

“I was left reeling, just very confused from something like this happening in Toronto, the most cultural diverse city in the world. Then I realized that this was in April and we were starting to wear masks outside.” Yung’s suggestion that COVID is claiming yet another series of victims through anti-Asian racism is proving to be tragically correct.

Soon after, he was approached by Starlight Media to make a film out of footage that had been shot by a crew of camera operators, sound recordists and other professionals just as the pandemic reached its peak in Wuhan. The Chinese group had been shooting a doc on the Yangtze River but production closed down in Wuhan and they “immediately pivoted and just started filming verité-style there,” Chang says.

At first hesitant, Yung, whom I’ve known for well over a decade, decided to take on Starlight’s offer. “I was handed about 300 hours of footage, which I treated like archival material. I think what was extraordinary for me was the opportunity as a film director to not have this preconceived notion of what the footage was about.

“I decided that I was going to look at it as objectively as possible and be in the editor’s seat. It was a remarkable experience actually, in the same way that I think Allan King may have approached his filmmaking. He wasn’t on location but he would be working with his team, carving out the drama from what they shot.”

Looking at the material, Yung soon realised that there were as many as nine different character arcs that had been captured by the Chinese crew. His immediate favourable response was towards a young couple from the country, Yin and Xu, who were in Wuhan in anticipation of having their first child. “It felt so emotional and real,” says Yung, and it was great to “get a sense of what they were doing behind closed doors in terms of grappling with their stress. To me, it was such a personal story that resonated more so than any of the others. So that took the forefront.

“There was this idea of the payoff at the end of the film with this couple because they are pregnant. I just knew that if we could get it to that place, there could be a positive statement about this world we’re in and how it just keeps going moving forward.”

Yung had found his approach to Wuhan Wuhan. He concentrated on finding the most interesting characters that had been covered by the crew. They’re all unusual in their own way, and often quite unlike what Westerners think of mainland Chinese people. Take Dr. Zhang, for example. She’s a psychologist from another province—not that well liked there because she’s an “alien”—who comes up with a great idea, attaching big photos to the front-line workers so the patients can identify with them.

Yung chose to follow her because, as he says, “Psychology in Asian culture, especially in China, is not a thing. I think it’s been a very slow ramp-up to understanding mental health and mental mindfulness in China as part of a way of treating problems. The psychologist’s presence in and of itself and her techniques were interesting to me. I was impressed by her character, and that she had a back story that we were able to capture, through her father’s revelation that he’s dying of cancer.”

Perhaps most interesting is Mama Liu, a feisty woman who insists on staying in a field hospital with her young son Lailai, who needs an advocate until he’s better. “The people in China are not all ‘yes’ people. I think that comes through in Mama Liu,” observes Yung. “She’s someone who when she’s not happy, she’s going to say it. She’s going to fight for the survival of her child Lailai and worry for him. It was a very byzantine kind of world that she was navigating. You see her frustration, you see her pragmatism, and you see that she’s fighting to get what she needs.”

Yung Chang’s film gives us a vivid sense of Wuhan under lockdown. “It is one of the largest cities in China, and in the world. It’s a city full of culture, where artists gravitate towards each other, whatever the discipline. For me to think of it as ground zero of COVID-19 was kind of shocking as I had been to Wuhan.”

Yung judiciously used drone footage even though he knows it can feel like a cliché. “I think for situations like this, it’s nice to see from above just to get a sense of the shape of the city and the scope of the lockdown.”

“Coming off my anti-Chinese racist experience, the material I edited into Wuhan Wuhan spoke to me. The Wuhanese, at the epicenter of the lockdown, are going through the exact same emotional beats and turmoil that that many of us were dealing with here, and probably all around the world.” Countering racism with a humanistic approach, Yung Chang’s Wuhan Wuhan is a powerful statement.

Part two: Pat’s report

Ngardy Conteh George’s Projects

For Ngardy Conteh George, producer/director at Toronto’s OYA Media Group, adapting to COVID has had different implications for projects in various stages of development and production. For some, the pandemic simply has meant hitting the pause button. For other projects, George says, it was often a matter of waiting, waiting, and waiting some more for broadcasters to give the green light. However, her team proved that the year of COVID wasn’t entirely played out in a state of limbo.

For George’s feature documentary in development, This Land of Ours, COVID is an opportunity to engage subjects in the telling of their own story. The film, which chronicles residents of the Caribbean island of Barbuda rebuilding in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma, had George making annual trips for research and preliminary shoots over the past three years. The coronavirus obviously makes further international production difficult. “Since lockdown happened last March, I’ve been asking the subjects in the film to self-record,” explains George. “We’ve done Zoom calls and there is a photographer on the island who does some filming when things happen that are relevant to the documentary.” She plans to return to Barbuda when possible, but now that COVID has reached the island, travel simply isn’t thinkable.

COVID’s presence on the island highlights the stakes of her film. George explains that cases were traced to a foreign traveller, whose illness had serious implications for a small island with no ventilators and threadbare health infrastructure. Moreover, as an outsider herself, George respects the lessons of her documentary and sought alternatives to filming on the island.

“Part of the story is about the developers who are coming in against the wishes of the majority of the local population to build and potentially damage the environment of the island,” explains George. “One of the developers is currently building a golf course on protected land and has had daily workers coming over from Antigua.” George adds that she heard local reports that a cluster of those workers tested positive and that the developers are further at odds with the Barbuda Council’s request for transparency. Moreover, her subjects filming on the ground include the principal of a local school, who’s witnessed the facility’s shutdown after a teacher tested positive amid the spread. “All these things are examples of why we’re making this film,” notes George. “People obviously have no regard for the local population.” While some naïvely call COVID “the great equalizer,” George’s experience reflects how the pandemic amplifies systemic inequalities that were already present.

George says that shifting contact with her subjects to Zoom and asking them to film themselves has been a relatively smooth transition because she established relationships during development. Moving forward with production simply means working at her subjects’ pace and within their comfort zones. She explains that conversations with subjects now begin with questions about their well-being and understanding what they mentally have the capacity to do, be it setting up a camera to record themselves or engaging in Zoom interviews. “It’s a matter of giving them flexibility, so that it doesn’t feel like a burden on their end,” George notes.

One of George’s other projects, Bam Bam! The Story of Sister Nancy, offers a case study in establishing relationships with subjects during COVID. Directed by OYA’s Alison Duke, the doc is about Jamaican dancehall DJ and singer Sister Nancy. George says that plans for the initial meeting and interview with Sister Nancy were supposed to happen at SXSW 2020 after Duke spent a year getting to know her over the phone. That meeting never happened, since the Austin festival was the first major arts event to cancel live activities due to COVID. Now, George says, they continue to build the relationship over the phone and work with local crews in New Jersey, where Sister Nancy lives, to capture necessary footage.

George says that with the crew and Sister Nancy’s help, they put together a development trailer to keep momentum. “That personal contact and then sharing the development trailer with her has helped keep her excited and know that we’re still moving forward,” says George. Similarly, for George’s project Mothering in the Movement (a working title), they’re moving ahead with a remote crew after finally getting the greenlight from documentary Channel following a year of waiting. She says this allowed them to record live events in a storyline about a poet searching to connect with the mother who abandoned her as an infant.

The director admits that COVID requires extra patience, but that shoots can continue with the right planning. “Because the film was in a holding pattern where we were told, ‘We could possibly give you the green light tomorrow, or we could give you a green light in six months,’ we went with worst case scenarios and planned out six months from then,” explains George. “We made the production schedule that far in advance so that we weren’t going into filming until this spring, which is probably going to be in the summer, really.”

Anything can happen while accommodating production delays, though. George says her film had an unexpected challenge of juggling multiple remote crews, travel restrictions, and protocols when significant life events for subjects played out in Jamaica and Germany and were too crucial to overlook. Travel restrictions from foreign governments pose challenges for filmmakers who want to capture pivotal story beats, but so too do conflicting production protocols between broadcasters, funders, and countries.

“We had our own protocols, and the CBC has a guideline that was our starting point,” says George, “but we had a framework of what to include, like what waivers crew members need to sign and now we assign someone from part of the crew as the COVID safety officer.” Transforming the office into a makeshift shooting space for interviews, adding high-end fans to circulate air, and extra time and funds for cleaning allow independent producers like George to continue as best they can.

For George, however, these precautions circle back to a filmmaker’s responsibility to her community. “Many of our employees have family members who’ve gotten COVID. We’ve had participants and emerging filmmakers who’ve gotten COVID, so it’s personally affecting all of us,” says George.

The NFB and The Curve

While independent producers adapt by project, institutions like the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) have used COVID to reflect upon their role in the industry. For Julie Roy, who stepped into her position of director general of Creation and Innovation in May 2020 after transitioning from her role as executive producer of the French Animation Studio, the early stages of the pandemic raised two perspectives: those of the NFB employees and those of the creators. For employees at the Montreal office, where Roy works, the transition to virtual offices was relatively easy since the NFB headquarters was in the process of moving from near suburbia on Côte-de-Liesse to Îlot Balmoral, next to Place des Arts. For filmmakers, cases obviously varied by production and province.

Outside Montreal, filmmakers’ ability to work inevitably differed by region. For the offices in Vancouver and St. John’s, Roy says, it was (relatively) business as usual with safety precautions in place. As with George’s experience, Roy notes that some filmmakers opted to have subjects film themselves, in some cases sending them iPhones to equip them for self-recording. As for protocols, the Board collaborated with the Documentary Organization of Canada for its massive survey and guidelines for production, as well as with Quebec’s AQPM union to standardize best practices.

However, Roy notes that what really resonated in this period was a strong sense of urgency. The NFB reflects this urgency in the project The Curve, a compilation of shorts produced amid the pandemic. “We felt that it was a historic moment and it was the first time that the NFB had this kind of national initiative,” says Roy. The online series comprises of 35 short film productions—in addition to the regular 35 works in production for the Board last year—that challenged filmmakers to document the developments of the pandemic or to create short works that reflect how life endures despite COVID.

“It was quite evident that we should be there in the field,” observes Roy. “There were two perspectives. The first perspective was that being there in the field is part of our DNA at the NFB. It is our mandate to document what is happening in society. But there was a strong argument that we needed to support Canadian creators and make sure that they can continue to work.” The process is quite an achievement with three dozen films conceived, created, and run through post-production, legal, marketing, and other streams in mere months when COVID paralyzed other corners of the film industry. “It was really quite ambitious,” says Roy.

In some cases, the projects for The Curve provided work for filmmakers whose productions had to pause due to COVID. Alicia Eisen and Sophie Jarvis, for example, were making the animated short Zeb’s Spider in the Vancouver office and took executive producer Shirley Vercruysse’s suggestion of making a short for The Curve when they had to put their film on hiatus. Their short riffs on the perils of Zoom conferencing. In other cases, like a block of films from the Ontario studio, the Curve shorts were opportunities for emerging talents to work with established mentors. Other shorts are simply the result of successful pitches traversing genres with documentaries, experimental works, and animation.

Moreover, The Curve anticipated the other seismic event that defined 2020—calls to correct systemic racism in all corners of the industry. The films reflect everything from the experience of young Black comedian Ajahnis Charley coming out to his conservative immigrant mother to Dene Nahjo filmmaker Melaw Nakehk’o’s portrait of her family reconnecting with the land off grid in the Northwest Territories. “We wanted to make sure that we chose filmmakers who were representative of different places geographically and from different perspectives and genres, and offer them the opportunity to choose a story,” explains Roy. “It was not always carte blanche, but an opportunity to ask filmmakers ‘What do you want to speak about?’”

The Curve still has projects in post-production and those that are online are helping drive traffic to the biggest year yet for the Board’s streaming portal. Canadian viewership at NFB.ca is up 85% (68% globally) as audiences turn to movies to pass the time and to find windows into experiences they can’t access in person due to COVID. For example, Andrea Dorfman’s How to Be at Home was a viral sensation during the second wave that offered reassurance to audiences with its animated poem about isolation.

The popularity of online viewing during COVID inevitably has the Board reconsidering how best to reach audiences. “We beat the annual number of Canadian views on NFB.ca over the past five years in just three quarters,” notes Roy. “It will influence the way we will launch our films because we had experience launching films directly online. It’s going to be more and more common.”

For audiences who don’t have the appetite to view COVID stories in the middle of a pandemic, the shorts in The Curve serve a basic function of capturing a transformative year. “It will be interesting to re-watch those films in 15 or 20 years from now and think about them,” says Roy. “There’s a value for heritage in this project capturing the present time. I’m proud that we were able to keep production going and to keep filmmakers working.”

How To Be At Home, Andrea Dorfman, provided by the National Film Board of Canada