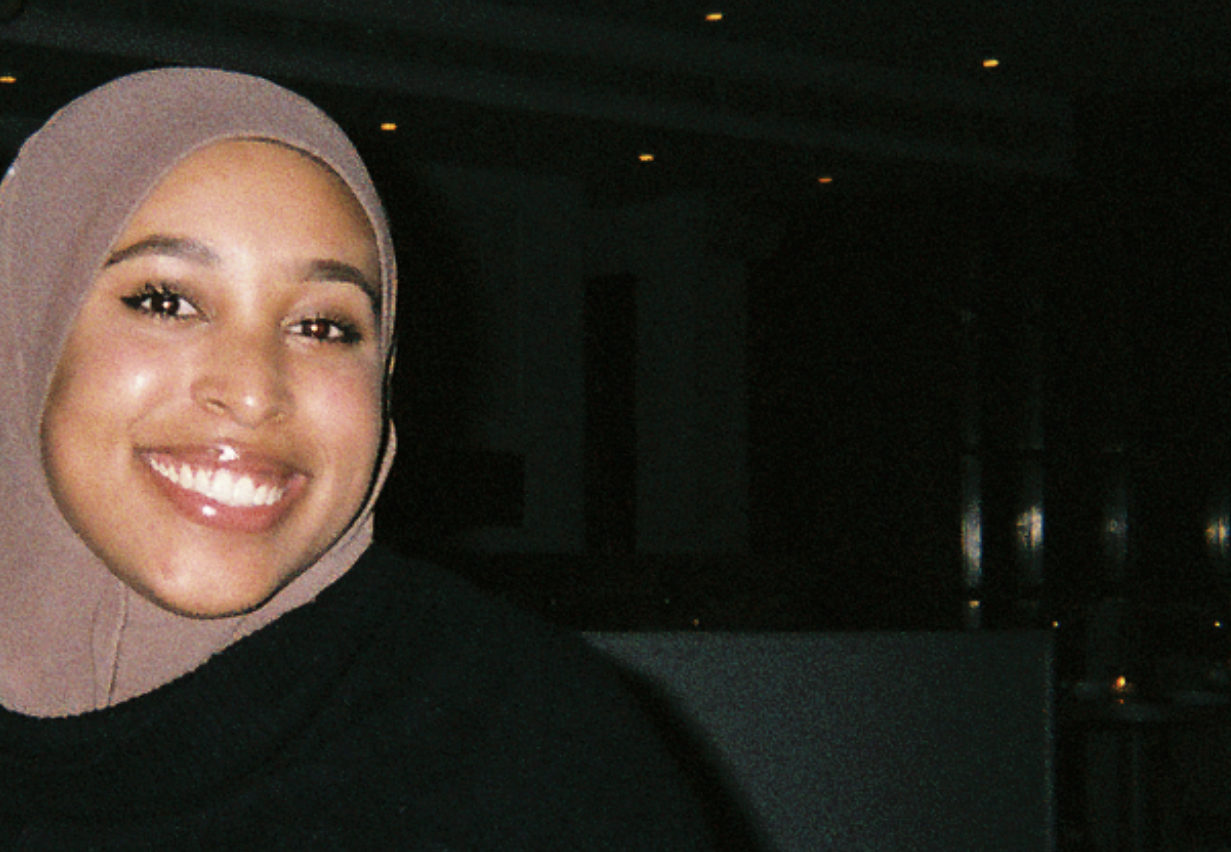

Niya Abdullahi represents a new generation of filmmakers changing the documentary field. She is one of the participants in this year’s Doc Accelerator Lab, supported by Netflix through the Canadian Storytellers Project, which bolsters emerging Canadian filmmakers by offering intensive workshops on the business of documentary.

For Abdullahi, the journey to becoming a self-starter filmmaker goes hand-in-hand with the initiatives to widen the playing field for documentary. Speaking with POV by phone, Abdullahi recalls having a moment of clarity when Hot Docs’ Docs for Schools program immersed students at her Scarborough high school with films from the festival’s selection. She recalls skipping class to educate herself through documentary and encountering a world of images unlike those from mainstream film and television. “I could see different people from different experiences and people from backgrounds that are similar to mine on screen, which was great to see,” notes the young Ethiopian-Canadian filmmaker. “There were films that featured Hijabi women and there was African representation.”

Abdullahi says she never planned to pursue film—she studied Business Technology at Ryerson University after high school—and channelled her passion into anti-Islamophobia and anti-racism activism. She recognizes that although running workshops afforded an outlet to talk about her experiences and let people see the world differently, she realised that more could be done. “If there’s no constant push towards change within those organizations or within those schools, then we really don’t know what the outcomes are,” observes Abdullahi. She says that despite feedback forums to collect final thoughts, the discussions generally ended with the completion of the workshops.

However, sparked by the engaging conversations she had with fellow Muslim-Canadians through her work and in an effort to further the dialogue, Abdullahi launched the YouTube channel Habasooda after receiving a grant from Ryerson. The channel features short documentaries in which Muslims from Toronto, around Canada and through the world engage in open conversations. “The best way to talk about Islamophobia or to even push people to change the narrative around who Muslims are and reflect our experiences is to give the microphone back to Muslims,” explains Abdullahi. She quickly corrects herself. “Or give it to them in the first place.”

Abdullahi says the initial grant prompted her to create “a media project that gets people thinking and allows them to see Muslims with different backgrounds and cultural heritages. Just seeing them on screen could change the narrative.” The Habasooda videos generally use a single question as a springboard towards unpacking the complexities of identity and representation. For example, an early video asks participants, “What does a Muslim really look like?” The answers acknowledge the usual media stereotypes—hijabs, religious symbols, etc.—and pivot to observations of quite diverse representations and instances of inner spirituality, as interviewees share their experiences and truths. Alternatively, videos invite audiences into the homes of Muslims worldwide to see how one celebrates Ramadan during a pandemic.

Despite shooting dozens of interviews independently with little more than a DSLR camera, Abdullahi says she didn’t consider herself a film director. It wasn’t until a YouTube comment from a viewer in Pakistan, who was struck by the vastness of Muslim experiences in these stories, called Abdullahi a filmmaker that she thought of herself as such. “That gave me the idea that I could actually use poetry to make films. I didn’t realize that what I was doing was filmmaking,” says Abdullahi.

That gift for visual poetry led to her short film By the Train, which observed a Hijabi’s unease and vulnerability on a subway platform. The film premiered in the emerging voices spotlight on the closing night of last year’s Regent Park Film Festival, offering a new opportunity for sharing stories about Islamophobia and inspiring audiences to think critically about the people with whom they share the city.

The filmmaker says that her exposure to the festival circuit at Regent Park inspired her to seek additional opportunities for professional development in Toronto. She recognizes her inexperience as a filmmaker made something like the Doc Accelerator Lab an ideal avenue to pursue. Abdullahi says that the self-directed nature of the Habasooda shorts say what she wanted to express, but that she knew she could do more with the right opportunity. “I thought it would be very different if I had a producer or somebody from the outside who was guiding me,” says Abdullahi.

Seeing the Doc Accelerator Lab tipped her off to aspects of the film business that aren’t taught in schools, like navigating the funding cycles or festival circuits. “I saw that it could equip me with the know-hows, like how to pitch, how to get funding, how to distribute,” she explains. “Those are words that I didn’t really understand or grasp [before]. Everything that I’d learned and everything that I that I’ve made so far is through YouTube.”

Through the weekly sessions that the Doc Accelerator Lab runs from April through September, via Zoom due to COVID, Abdullahi says she’s had the chance to learn these aspects of the industry. The Lab also gave the cohort an intimate and safe space to discuss what it means to be a racialized person trying to break into the film industry when systemic barriers and a history of white/colonial lenses have shaped the stories that audiences and funders often use as benchmarks for success. The Hot Docs porject is one of several partnerships that Netflix has with like-minded organizations in Canada, like Inside Out 2SLGBTQ+ Film Finance Forum and the Canadian Academy Directors Program for Women, to give up-and-coming filmmakers the chance to break through. The latter, for example, helped Halima Ouardiri make it to last year’s Berlin Film Festival with the short doc Clebs, which won the Crystal Bear for Best Short Film. This year’s Inside Out Film Financing Forum, meanwhile, features Canucks Luis De Filippis, Shant Joshi, and Rodrigo Barriuso, among others.

Moreover, the Doc Accelerator Lab gives a chance to experience the festival firsthand with access to the industry component, like the new SWAP system that enables digital networking. “It’s been a great way to understand the world of documentary film in general,” notes Abdullahi. “I’m hoping to have more professionals in and learn more about what I could do as a filmmaker to keep my integrity.” She plans to channel the experience with the Doc Accelerator Lab into her next two projects, a doc series called Muslim Love and a doc about Quebec’s Islamophobic Bill 21, which banned the wearing of religious symbols.

Like her early exposure through the school program, the Doc Accelerator Lab gave Abdullahi a chance to see the films at the festival and, in turn, encounter the power of seeing her experiences on screen. She cites Jessica Beshir’s Hot Docs favourite Faya Dayi as a highlight. The film is a sumptuously shot visual poem about an Ethiopian plant, khat, and the larger legacy of colonialism.

“It was beautiful,” says Abdullahi. “It was just so real and so authentic.” She notes the power of hearing characters speak Harari properly, as opposed to foreigners playing a role, while injecting the film with songs, poetry, and culture. “Islam is very much deeply embedded within our culture as Harari people, so that’s what I mean by good representation and doing it right. People that grew up there understand. You leave that film feeling so full.” Maybe at a future festival, one of her films will leave a budding artist feeling equally enriched.