If hybrid documentaries were all the rage in the 2010s, now is the time for hybrid dramas. An emerging trend sees filmmakers cast people as themselves in stories dramatizing their experiences. These films follow a decade in which documentaries increasingly gravitated towards fictional elements while Hollywood doubled down on non-fiction properties. New evolutions in hybrid film employ the power of self-representation to move audiences with the drama of our increasingly fragmented world.

The popularity of hybrid docs, loosely defined as non-fiction works that incorporate elements of dramatization and performance, is reframing the definition of documentary itself. Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2012) features Indonesian right-wing murderers re-enacting their crimes from the mid-1960s civil annihilation of the Communists after the overthrow of Sukarno. These über-theatrical performances include musical numbers and Spaghetti western drag shows amid interviews with the criminals. Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell (2012), meanwhile, incorporates dramatic B-roll within a tapestry of home movies. The collage of archival elements and re-enactments evokes the ways in which memories become fictitious as people re-interpret them over time. The films of Robert Greene — Actress (2012), Kate Plays Christine (2016), and Bisbee ’17 (2018) — contrast conventional elements of documentary and explore the fissures between social roles, media images, and historical records, respectively. Whether it’s Brandy Burre playing herself, Kate Lyn Sheil interpreting ill-fated newscaster Christine Chubbuck, or local workers re-enacting history, Greene’s interplay between documentary and drama finds truth in performance.

Hybrid Docs vs. Hybrid Dramas

These hybrid docs go beyond docu-drama or outright re-enactments. Rather, they incorporate elements of fiction within non-fiction to meditate upon the reliability of documentary images. In some cases, the dramatic content compensates for an absence of archival material. Much is written about the role of absence in these films (see Daniel Glassman’s Oblique Strategies, for example), but the interplay between documentary and drama can also underscore power structures that determine what gets recorded by history, how stories are framed, and who tells them, via radical presence. Hybrid dramas reflect these concerns by inviting people to tell their own stories.

The mixed composition for hybrid dramas features narrative tales injected with elements of non-fiction. Where hybrid docs use mixed compositions to intellectualize notions of actuality/factuality, hybrid dramas harness non-fiction elements to create empathetic and participatory portraits of people on the margins.

More recently, hybrid dramas are going mainstream with A-list directors and/or stars, like Clint Eastwood’s The 15:17 to Paris), Ricky Staub’s Concrete Cowboy (2020, starring Idris Elba), and, most notably, Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland, starring Frances McDormand. As evidence of the latter’s effectiveness, Nomadland made history as the first film to win both the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival, captivating both the industry and the public with a film of, and for, the moment. What emerges in this interplay between doc and drama is a new hybrid that employs actuality, realism, and authenticity to let subjects connect with audiences while reflecting their experiences as they know them.

In Vino Veritas

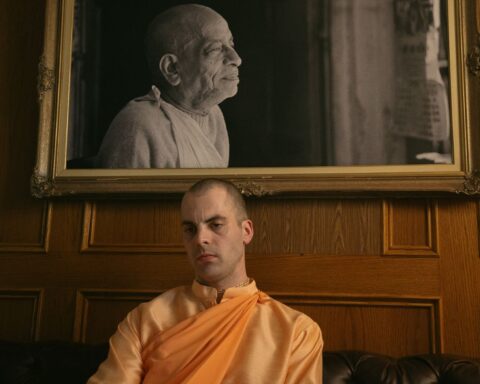

Not quite a mockumentary, but not quite a documentary, Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets (2020) by Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross (Western, Contemporary Color) embodies this new hybrid form. It purports to take place inside a Las Vegas pub, The Roaring ’20s, for its last hurrah before closing. The filmmakers document the patrons mingling, drinking, and arguing. The film looks like an observational documentary with its fly-on-the-wall aesthetic and Altmanesque dialogue, which flows as freely as the liquor. However, the bar is really a soundstage in New Orleans modelled on a real bar in Vegas. The characters are personalities whom the Rosses encountered in pubs nationwide. The booze is real, though, as are the conversations and the questions about addiction and community evoked by the interactions.

If every element of the film is constructed, but the action inspired by the conceit is spontaneous, is the result a documentary? Even members of POV’s editorial team disagree whether Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets is a drama or a documentary. However, they agree that the film fascinates with its shape-shifting form. Ultimately, I see Bloody Nose as a non-fiction essay about alcoholism and tavern culture. Bloody Nose eschews the aesthetics of the aforementioned hybrid docs, which clearly distinguish dramatic elements from documentary ones. It dissolves the barrier between fiction and non-fiction, inviting real people to enact the drama of their lives.

Eastwood Hops the Hybrid Train

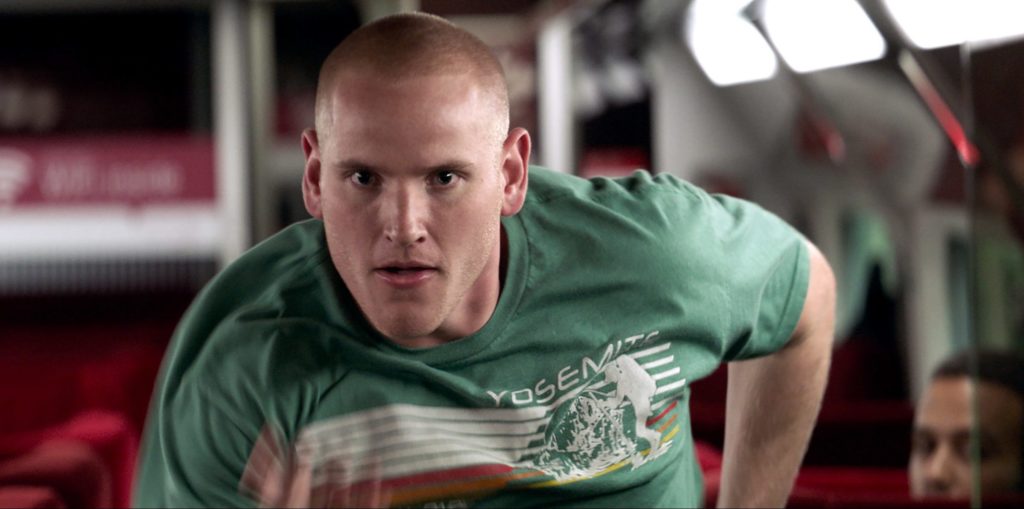

The “mainstreaming” of hybrid dramas begins with Clint Eastwood’s The 15:17 to Paris. 15:17 adapts the non-fiction book of the same name about a 2015 incident in which American military servicemen Spencer Stone, Alek Skarlatos, and Anthony Sadler subdued Moroccan extremist Ayoub El Khazzani during the titular train ride. In a departure for mainstream commercial cinema, the film features Stone, Skarlatos, and Sadler as themselves instead of hot bankable stars.

15:17 offers episodic moments preceding the fateful voyage and climaxes with a dramatic re-enactment of the incident that draws upon the men’s collective memory. In a somewhat macabre twist, all the “actors” in the train sequence (save for Ray Corasani as El Khazzani) endured the original incident. French-American Mark Magoolian returns to re-enact the moments in which he was shot and nearly died. Brit Chris Norman returns to help subdue the gunman. The fellow travellers, paramedics, and police also gamely relive the event. Eastwood’s no-frills style lets the attack play more or less as it transpired—quickly, brutally, and chaotically—to let one experience the moment as the participants did.

If The 15:17 to Paris successfully recreates the event, Eastwood’s drama remains unsatisfactory because, simply put, the three leads can’t act. The dramatic inertia of the film sees the heroes exchange stilted dialogue as Eastwood guides the train to its eventual bloodbath. The friends note in interviews that Eastwood deterred them from pursuing acting classes and directed them to act naturally and be themselves. If every minute of 15:17 is emotionally flat, though, it’s experientially true as it lets the characters re-enact their heroism without embellishment. This terribly fascinating and fascinatingly terrible exercise demonstrates how hybrid dramas afford subjects agency by offering a dramatic remove through which they may both process and share their experiences.

Close-up on Chloé Zhao

Most significant in the new wave of hybrid dramas is the work of Chloé Zhao. Her features Songs My Brothers Taught Me (2015), The Rider (2017), and Nomadland couple agency and authenticity with poetic realism. Zhao’s films predominantly feature non-professional actors creating variations of themselves or playing themselves explicitly. Unlike Eastwood, Zhao attributes her practice to economic necessity as much as artistic impulse. Nonetheless, in giving voice to figures frequently marginalized in the USA’s heartland, Zhao’s films profoundly deconstruct the myths of the American dream.

Zhao’s first feature, Songs My Brothers Taught Me, depicts the lives of Lakota youth on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. She drew upon the four years she spent on the reservation to make the film, which reflects on the youths’ connection to their home in comparison to her sense of rootlessness. Made on a shoestring budget with Zhao loosely scripting scenes the morning of each shoot, Songs features John Reddy and Jashaun St. John as siblings Johnny and Jashaun Winters as they go about their day-to-day lives: Johnny drinks, goofs around with his friends, and prepares to leave the reserve while Jashaun clings to her roots and considers following her late father’s career in rodeo.

The spontaneous nature of the production allows unscripted moments to permeate the drama. A scene in which Jashaun visits the charred remains of her family home after a fire and tearfully sifts through the ashes while searching for traces of her childhood renders irrelevant the line between drama and documentary. The film admittedly reflects the limitations of the young leads’ acting experience, yet Zhao’s minimalist inclination affords the portrait of youth in America’s Badlands layers of complexity that few films by outsiders achieve.

Songs perhaps serves as a draft that Zhao would refine in The Rider. The film features Sioux cowboy Brady Jandreau, whom Zhao met while filming Songs, as Brady Blackburn, and follows him as he tries to return to the saddle after a rodeo accident in which a horse trampled him in a rodeo and stepped on his head and nearly killed him. Through the insecurity Jandreau faces in his own life, The Rider follows Blackburn as he considers that his passion may outlive the physical limitations of his body. Moreover, a lack of education and declining opportunities mean that, for both Jandreau and Blackburn, riding is one of few options left unless he leaves his community. As Jandreau’s friends, family, and colleagues fill the supporting cast, Zhao’s portrait doubles as a sociological survey of the hardships faced by contemporary ranchers.

Jandreau’s experience as a rodeo performer befits the production since The Rider’s dramatic weight rests on Blackburn’s connection to the horses. The scenes in which Blackburn trains horses are essentially footage of Jandreau performing his day job with Zhao filming his actions. When he leaves work and roams the frontier, lyrical shots favour Jandreau riding horseback or simply tending to the animals. Zhao limits dialogue and steps back, letting the rider’s own recovery, relationship to the land and animals, and control over his destiny guide the drama. Shot mostly around dawn and dusk to accommodate Jandreau’s work schedule, the magic hour cinematography by Zhao’s partner Joshua James Richards offers an elegiac portrait of the American cowboy. The result is a poetically observed character study that humanizes a misunderstood corner of the country’s heartland, and the struggle to retain an identity and lifestyle that seems to be setting with the sun.

Nomadland and the New Hybrid Drama

With her third feature, Zhao has perfected her hybrid approach. Nomadland adapts the non-fiction book of the same name by Jessica Bruder, a sociological study of itinerant workers who travel America in mobile homes and vans in search of seasonal work. What distinguishes Nomadland from Zhao’s prior work is the presence of Frances McDormand. The two-time Oscar-winner is the antithesis of Zhao’s previous casting choices. However, McDormand yields her star power to her director and, more significantly, the personalities depicted in Bruder’s book.

McDormand’s character Fern is one of two prominent fictional figures in Nomadland played by professional actors. (The other is Fern’s fellow nomad and love interest played by David Strathairn.) Nomadland follows Fern as she travels the country in her van, Vanguard, after the closure of the sheetrock plant in her hometown of the ironically named Empire, Nevada reduces the city to a ghost town. (In reality, even the zip code was disbanded.) In an effort to recreate Zhao’s trademark authenticity, Nomadland incorporates props from McDormand’s own life into Fern’s van, while the actress worked itinerant jobs including picking orders at an Amazon warehouse, harvesting beets during winter, and scrubbing toilets at a campsite. Nomadland depicts McDormand in action at these locations alongside people who work there regularly.

As Fern learns the nomadic life, she encounters figures like Linda May, the chief character in Bruder’s book. Linda May teaches Fern the tricks of the nomadic lifestyle and helps her secure seasonal work. Other nomads appear fleetingly, including figures from Bruder’s book like Bob Wells, who promotes the movement for #vanlife through his YouTube channel and annual two-week rally, the Rubber Tramp Rendezvous. Scenes at this camp—actually a meticulous re-creation of the event populated through a call for nomads—are cinema verité, pure and simple. McDormand roams the campsite by twilight as the camera observes the magnitude of the transient community. The wireless microphone captures the ambient sounds of Americans forging their destinies anew. In locations like the camp or Fern’s workplaces, Nomadland draws upon Zhao’s adaptable style, incorporating figures encountered in such sites and constructing scenes around their life experiences.

Fern ostensibly replaces Bruder, a prominent figure in her own book who lived the nomadic life just as Zhao did while making Nomadland. In addition to substituting for Bruder, McDormand plays a role comparable to a celebrity host in a documentary, staging conversations with people for the camera. Think Leonardo DiCaprio in Before the Flood, but with better research and preparation.

Much of Nomadland features McDormand in conversation with nomads like Charlene Swankie, another figure from Bruder’s book, who tells Fern about confronting her mortality following a cancer diagnosis. Linda May, meanwhile, recites to McDormand her life story and veteran van-life tips that she’s clearly shared with many nomads before. McDormand says relatively little as Fern listens to the nomads reflect upon the losses they faced, the dreams they abandoned, and the sacrifices they made to uproot themselves in order to survive. The stories echo the pages of Bruder’s book, evoking a kind of verbatim theatre performed by the speakers themselves. The majority of the nomads Fern encounters are elderly people and, as with Songs and The Rider, the film affords characters on the margins of society a forum to articulate their struggles. It emphasizes their resilience after American capitalist society discards and abandons them.

Emphasizing Presence

Comparing Zhao’s work with another hybrid drama that also premiered at TIFF this fall, Ricky Staub’s Concrete Cowboy, demonstrates the singularity of her approach. Concrete Cowboy stars Idris Elba and Caleb McLaughlin in a tale of the Fletcher Street cowboys being displaced in the name of development, with Fletcher Street riders like Jamil Prattis and Ivannah Mercedes featuring in minor roles as fellow cowboys. Apart from a mawkish scene in which the gang helps the paraplegic Prattis ride again, and some opportunities for Mercedes to flirt with McLaughlin in a romantic subplot, the authentic people and stories are left to the end of the film, and they appear as interviews within the credits. The inclusion of the real subjects mostly serves to legitimize the tale in a clichéd “based on a true story” post-script; their presence is almost an afterthought. The relationship between fiction and non-fiction elements is distinct. Zhao, on the other hand, constructs her drama around the figures who populate it. Nomadland demonstrates how hybrid dramas can deconstruct and elevate scripted content by volleying art and life in a seamless interplay.

Moreover, as Fern listens to the nomads’ stories, Zhao lets McDormand’s dramatic experience accentuate the emotional weight of their tales. Through her authentic performance, McDormand offers an empathetic ear. This exchange between real subject and professional actor demonstrates how Nomadland employs true hybridity by drawing upon two distinct sources and by harnessing unique but complementary energies. Where 15:17 to Paris fails to inspire emotional connections, McDormand’s dramatic chops provide punctuation marks that let the nomads’ stories resonate. Seeing the star moved by the experiences of people like Linda May and Charlene Swankie, Nomadland devastatingly reminds audiences that these are true stories lived by real people.

These hybrid dramas emerge at a moment when conversations in film frequently emphasize representation and inclusion. Zhao’s films illustrate how one can serve subjects’ experiences fairly by making them active participants and ensuring that their perspectives are the dramatic focus. As the leads with no acting experience react naturally to the uncertainties they face, Zhao’s dramatic conceits provide safe distances between non-actors and the events in their lives. The line between fiction and non-fiction can be a fine one, and Zhao demonstrates its potential for dramatic effect.