Death & Taxes

(USA, 86 min.)

Dir. Justin Schein

Section: U.S. Competition (World premiere)

The United States of America was founded on three principles: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. At the same time, Benjamin Franklin famously quipped that the only two certainties in life were death and taxes. Though he did not originate the use of this phrase (its origins date back to earlier in the 18th century), he certainly popularized it and, until recently, it held steadfast. Now, the wealthiest among us wish to make one of these unshakable truths obsolete. Spoiler alert: it’s not death.

With the rise of the billionaire in the 21st century, many of the world’s richest people are able to avoid paying a substantial amount in taxes – and they don’t make it a secret. In a presidential debate with Hilary Clinton, Donald Trump once asserted it “makes me smart” when confronted about not paying federal income tax on a past casino business. It’s one of the most memorable clips played during Justin Schein’s insightful documentary Death & Taxes, which wrestles with the top percent’s efforts to safeguard their wealth and the economic inequality that has widened as a result.

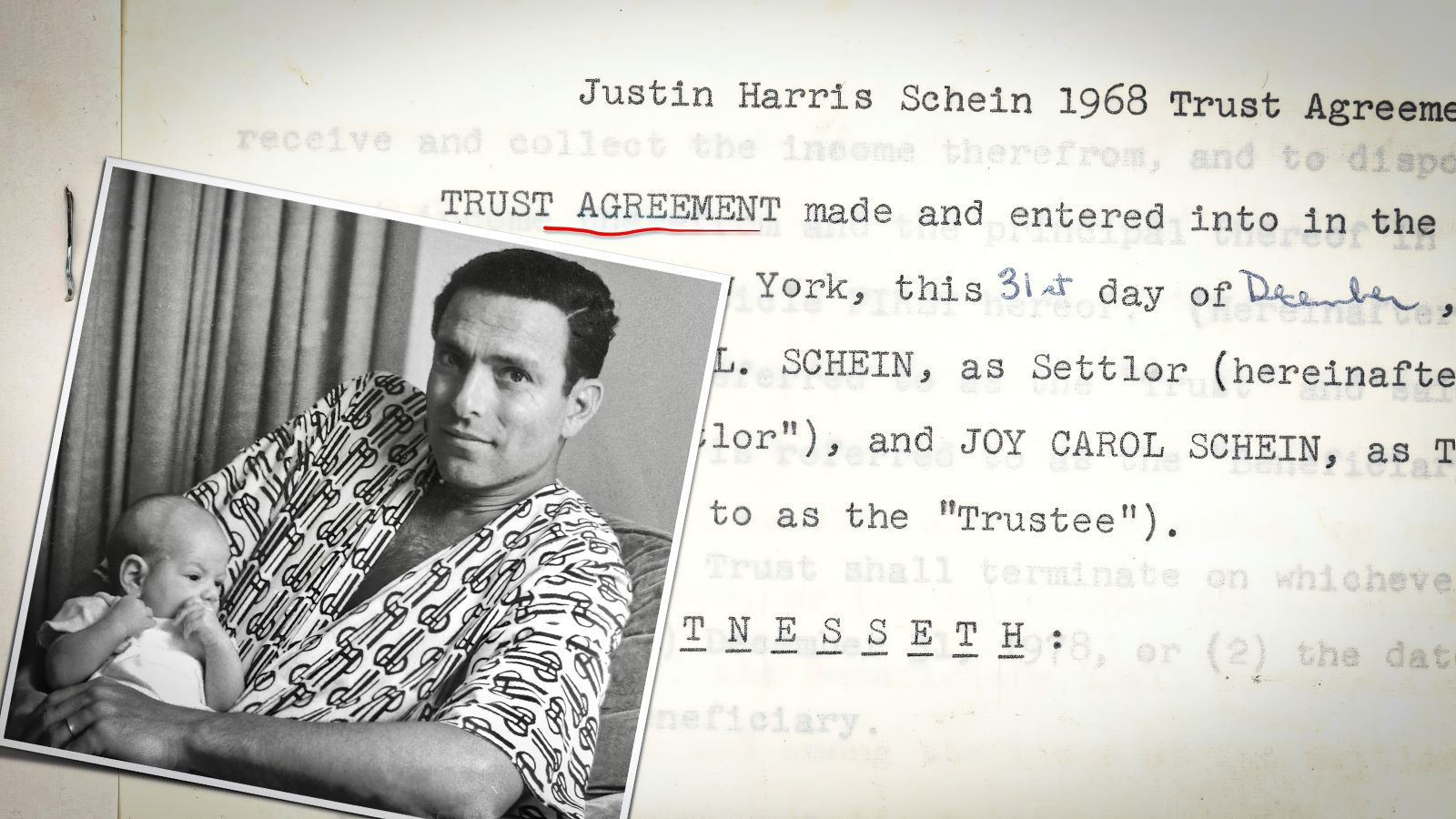

Thankfully, Schein does not attempt to tackle this subject through the lens of Donald Trump specifically, like many filmmakers have surely done before. Instead, his entry point comes from a more personal place: his father, Harvey Schein, who died in 2008 following a battle with lymphoma. During the final years of his life, Harvey was determined to maintain his money after his death, which he insisted was at risk due to America’s infamous estate tax – notably nicknamed “the death tax” – which, at the time, sat at 50%. The film uses this as a jumping off point to look back on his life story, which Schein situates amid the all-American tradition of tax evasion.

The film tells how Schein went from growing up in poverty during the Great Depression to becoming a successful Columbia Records executive and one of New York’s leading CEOs. Although the particulars of his wealth are not specifically stated, it is enough to help support his two sons, specifically Justin, whose decision to become a filmmaker is at odds with his father’s desire for him to have a stable, white-collar career. As it turns out, this is not their only point of disagreement, and another one is the estate tax itself. Justin believes it can help offset the country’s wealth gap. Harvey believes it is antithetical to the American Dream itself.

Of course, as Schein’s initial exposition explains, the estate tax is practically a non-starter for most American households. It affects 0.1% of them yearly and, even for these exceptional cases, exempts the first several $27 million per couple. So, what is Harvey really complaining about? This is what the first half of Death & Taxes tries to parse through a balance of family biodoc and historical investigation. On one hand, we learn more about Harvey, whose childhood paved the way for an incessant frugality and barnstorming personality that sent him straight to the top tax brackets. His charming personality and unbridled assurance in his own beliefs make him a compelling central figure to follow, while fun family videos (which Shein shot himself) and old photos capture a nostalgia for the nuclear family that invites sympathy for his story.

On the other hand, we learn about America’s broader economic history, specifically how the very generation that received post-recession bailouts from the government helped uphold “trickle-down economics” in the 1980s, which safeguarded predominantly white corporate wealth from under-served communities and a struggling working class. Harvey insists on never giving handouts, even though his education came from the 1944 G.I. Bill, which oversaw financial aid for veterans of World War II. Schein’s many different talking heads directly interrogate this should-they-shouldn’t-they debate of taxing the rich, which editor Brian Redondo cuts together into a balanced but firm perspective on the issue.

Early in the film, Justin tells his wife he wishes to make a film about privilege, which he does, although only to a degree. It becomes clear that Harvey weaponizes hypocrisy in his economically isolationist views. Meanwhile, Justin’s refusal to reveal the specifics of his family’s wealth – to which he admits to directly benefiting from – partially takes away from the depth of his examination (legal reasons notwithstanding). Harvey wants to avoid taxes, yet it’s never clear how much of his wealth is actually at stake, nor how much of Justin’s own support may be affected by that. Call it a conflict of interest.

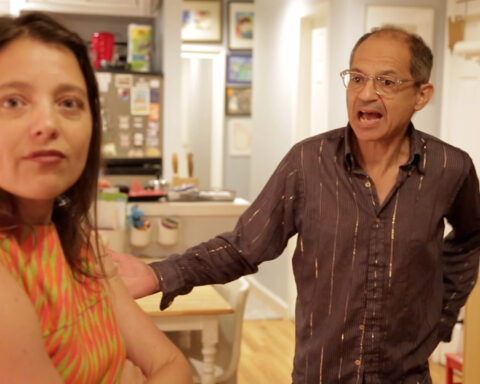

In fairness, the numbers aren’t really the point. What matters is the extent to which Harvey keeps a grip on them, which becomes the dramatic driving force of the film’s moving second half. As Harvey and his wife, Joy, grow older, Harvey seeks to move to Florida, where there is no income tax. After a while, Joy becomes miserable being away from home, longing to be in New York where she can continue to pursue her passion for dance education. Harvey’s stubbornness leads him and Joy to temporarily divorce, leaving Harvey disgruntled and, eventually, deeply regretful. Not long afterwards, Harvey becomes sick and is forced to stare his mortality square in the face.

Leaning toward a more observational, sensitive portrayal of his father in his twilight years, Justin reveals that the most powerful antidote to his father’s insistence on keeping his money is to show what happens when it is all he has left. Money can’t buy you happiness, even if you manage to evade taxes in pursuit of it. It’s not a novel message, but one that continues to bear repeating as the wealth gap grows larger and larger. After all, it’s one Justin had to learn himself, reflexively incorporating a coming-of-age throughline into the film as he becomes a father to two sons. Through working on this film, Justin appears to have learned from his father’s mistakes, which is perhaps a far greater inheritance than any dollar amount.