Canadian filmmaker Sean Menard was born the same year as MuchMusic, and it seems fitting he has taken on the task of documenting the rise and fall of the “Nation’s Music Station.” What started out as a scrappy subset of the City-TV empire (think Videodrome if you want the more macabre manifestation, but with more Duran Duran videos) in 1984, the fledgling channel soon became one central way for Canadians to experience musical acts both classic and groundbreaking. 299 Queen Street West became an address almost as iconic as what was contained within it. With a ride range of video jockeys like George Stroumboulopoulos, Sook-Yin Lee, and Terry David Mulligan bringing their own tastes and interests in sub-genres to bear, MuchMusic grew from its humble beginnings to become nothing short of must-see TV for any music nerd.

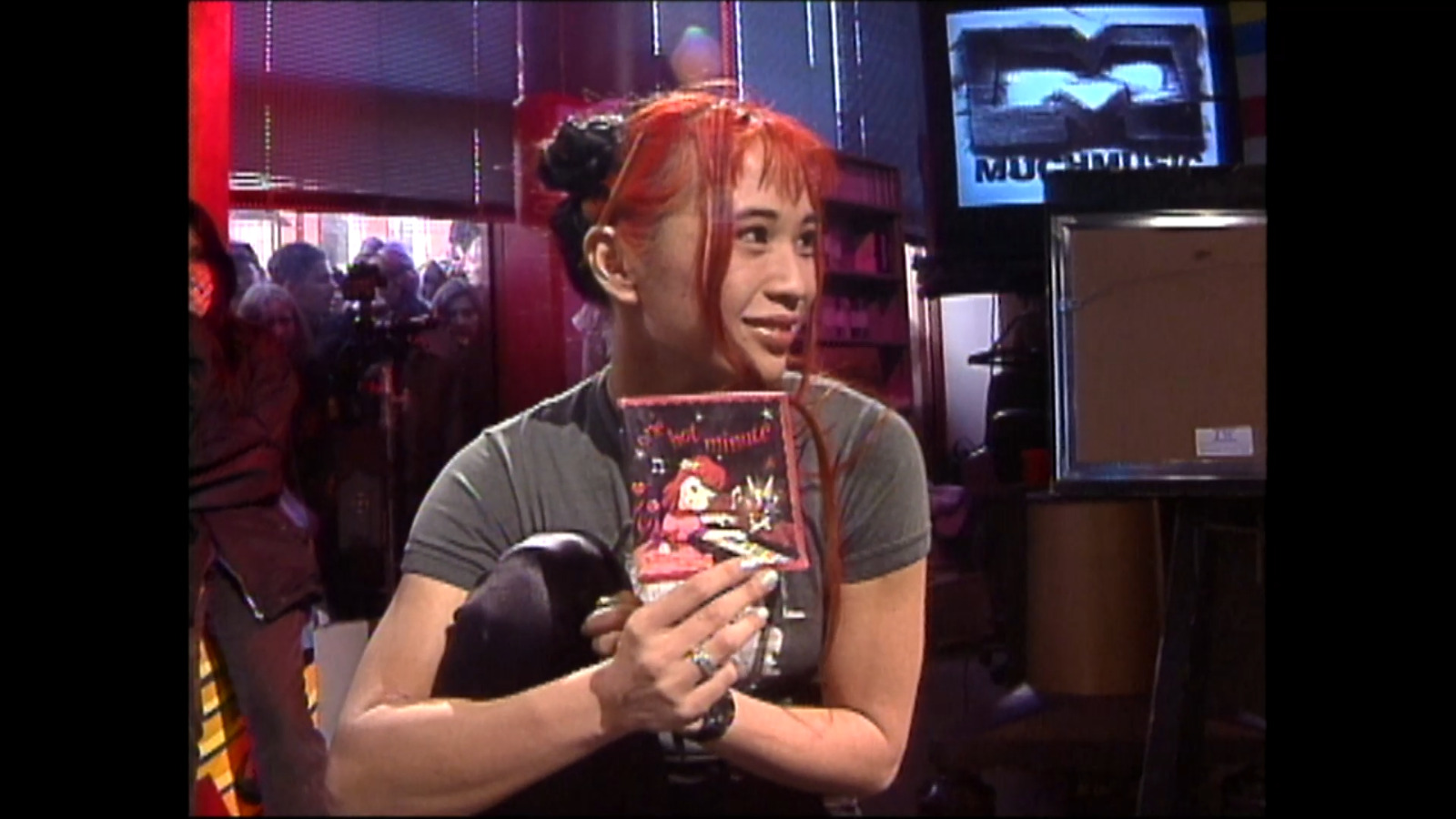

Menard’s film 299 Queen Street West is both celebratory and bittersweet, focusing on the personalities that were at the forefront of the station’s consistency, and the many artists who warmly responded to both the unique looseness of the affair, but also the way that the interviewers would take things seriously enough for MuchMusic to be more than just another stop on the publicity tour. With access to Much’s astonishing archive, we see clips as varied as a preposterously young Justin Bieber clearly giddy at realizing a childhood dream to appear at 299, to a churlish Noel Gallagher and Bonehead from Oasis doing a fantastic acoustic set, clearly annoyed that his brother Liam is off somewhere “shopping” rather than showing up on time for their scheduled gig.

From dance crazes during Electric Circus to Ed the Sock at Woodstock ’99, Much is shown to live up to the desire to showcase all music to an eager public riding the visual music wave. Soon the likes of YouTube would crush its popularity (I was horrified to learn the brand still lives on as a TikTok account), but Menard’s film provides a wonderful way to both revel in the nostalgia and begrudge some of that sense of community now lost in a far more fragmented age where access to everything has supplanted an address where all could gather and, at Speakers’ Corner, even where one’s voice could be heard.

We spoke to Menard prior to one of his roadshow screenings at his home town of Toronto, a day before he is to drive to Windsor to screen at WIFF as their closing film. “They’re rolling out the red carpet, and they’re the only Canadian festival that’s got this film because of their passion for cinema and what I made here,” Menard said from the road.

We spoke of the challenges of bring the film together, as well as some broken promises and other travails have resulted in him taking on the task of self-promotion, and the very complicated nature of getting a Canadian documentary in front of Canadian audiences.

POV: Jason Gorber

SM: Sean Menard

The following has been edited for clarity and concision.

POV: I want to talk about your first experience with MuchMusic and the era that you came up on of actually watching music videos.

SM: My first memory with the channel was probably watching Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit. I was in elementary school, and that kind of blew my mind.

POV: What was it was like in that period of the early-’90s having access to, essentially, visual radio?

SM: The part that I loved was that, on MuchMusic, you never knew what you were going to see or hear next. It was at a time when music was ultra-diversified, so it was country music, it was electronic music, it was grunge, it was hip hop. I was just sitting there, having my little mind absorbing all of this visual art, and different types of music that I normally would never have come across, I maybe didn’t realize how impactful it was on my life until I started making this project.

POV: How significant was the art of music videos, particularly during that era, to your art of filmmaking?

SM: Significant. It definitely made me. When I sat down to make the film, I wanted to recreate the experience of what it was like to watch MuchMusic, so I leaned heavily into archives. Visually, my film is [composed of] things that you saw on the television while watching that channel. The goal was to bring the audience back to what it was like being a young Canadian and having your culture completely absorbed, or being open to this whole new wave of culture. That was the inspiration for trying to make a documentary about this incredible channel and the way that the channel was broadcast.

POV: Were you aware at the time about how different their schtick was from, let’s say, an MTV? Had you had any experience of what was going on in the States at the time?

SM: No, I had zero knowledge. Even up until making this project, it didn’t dawn on me how different it was. I had sent it to my composer Tom Caffey who spent his whole life in Los Angeles. He composed my last film, The Carter Effect, then he went on to do the Michael Jordan Last Dance series for Netflix. He’d just come off that and I had sent him a rough cut of 299 and he called me right away and was just blown away. He had watched these artists and he had seen them and listened to them in interviews on MTV his whole life, but he had never seen them like that, being real, authentic human beings. It’s really a testament to the individuals that were interviewing, the VJs, because they were able to be real, authentic people. And that in turn allowed the artists to feel so comfortable in a live environment to just be themselves.

That was the moment when I started to realize this might be something that’s beyond the Canadian market, or a Canadian audience to be interested in. Getting in to SXSW, which has become one of the biggest film festivals in America, was another indicator that this isn’t just some story for Canadians.

POV: Let’s talk specifically about the structure of the film, using the archive footage with contemporary interviews, and how you settled on that mode of storytelling.

SM: I’ve been trying to make an all-archives film for years, but I’ve never come across something that’s had enough of a substantial archive base to work with. I originally started filming with a couple of the VJs, and then I would take their audio and put it underneath their clips, and even engaging with them on the phone, discovering how their voices are the exact same and it’s taking me back. I wanted to find a way to not juxtapose this great time period and footage, and avoid time travel back and forth from 2023 when you’re seeing subjects in an interview. I wanted their voices to stay talking about what’s happening in live time, and tell this incredible story of the rise and fall of MuchMusic, but also more importantly, the bigger story of where music went from the rise of the music video into the Internet/YouTube era.

POV: Of all the VJs that went on to international success, there’s John Roberts now at Fox News. His absence as an interviewee is, at the very least, notable.

SM: I don’t follow politics very closely, so I wasn’t even aware of his potential to create any sort of distance with the audience or polarization. It really just came down to [the fact that] I was trying to find one or two stars or characters for each generation, who were there long enough and could tell the story. I never contacted Christopher Ward or J.D. Roberts, who were the first two VJs, although they’re highlighted in the film. For me, it was simply a creative choice of wanting to highlight the ones I did. There were several that, for reasons I’m not going to get into, didn’t want to participate in the film. I’m just thankful for the ones who did, the energy they brought to the interviews, and beyond that, the ones that are coming out to the tour to support the film.

POV: What was that experience like in Austin? We’re so weird about telling our own stories in Canada, feeling, à la Mike Myers’ Wayne character who got his start on Much that “we’re not worthy.” People at SXSW think they’re hip and know every story there is to tell about music, and then they see something like Noel Gallagher sitting on his ass on Queen Street.

SM: With no Liam anywhere in sight! Yeah, that was the first audience that had ever seen the film, in the world, which is kind of messed up if you think about it, right? Why is this not premiering in Canada?

POV: We’re going to get into that, I promise you.

SM: I mean, that’s a battle I faced even on my previous film [The Carter Effect], before it went on Netflix and was around the world streaming in its first week, and that was a love letter to Toronto! But you’re right, for whatever reason in Canada we don’t celebrate our history as well as other countries do, especially our positive stories. And I think we can all agree that they’re interesting beyond the fact that they just happen to take place in Canada.

It’s very rare in 2023 to get into a film festival the old school way, where you just submit, and then you wait and hope that the programmers are watching it and it gets elevated. I didn’t realize how much of that world no longer exists. I’m sitting there in Austin at a directors’ table the night before my screening, and you’re meeting other filmmakers and chatting about who produced your film. Everyone’s going around the table and saying Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and then it’s like, “Uh, I produced it myself?” Awkward silence.

The SXSW programmers all made sure to come and talk to me because the film spoke to them in a way that where they saw themselves. The early Much origins felt like a reflection of how their scrappy festival in Austin, Texas started out and now it’s growing into what it is today.

POV: So, let’s talk about your challenges of having the same kind of grand premiere here in Toronto.

SM: I’m at the point where I’m ready for the first time to open up about this. I’m very disappointed in my homegrown festival, to be honest with you, as it’s the festival that helped launch my career in 2017.

POV: And by homegrown festival you mean TIFF, not Hot Docs.

SM: Correct. Back with The Carter Effect, I was on stage with Drake and LeBron James who became my executive producers. There was always a question in my mind: “Did this film get in this festival because of who my producers are? Is that what TIFF has grown into? Is it now simply a festival where it cares so much about who is going to be on the red carpet, and less about the quality of the film, or whether the audience is really going to embrace and love the subject matter?” With 299, I named it after, in my opinion, the most famous address in our Canadian pop culture history. Plus, it happens to be literally down the street from TIFF. So, my film didn’t get programmed, I met with Ravi [Srinivasan] shortly after the festival, and he expressed his frustration, and his, well, I’ll just say, his passion and love towards this film.

POV: So, just so we have the timeline straight: You originally submitted for a world premiere at TIFF 2022, and they rejected it. You had a conversation with Canadian programmer Ravi Srinivasan following that TIFF, and this was all before playing SXSW 2023?

SM: Correct. The conversation I had with Ravi was that there were a lot of films that they were sitting on in the Canadian market specifically because people were waiting for audiences to show up post-COVID. There were films that they wanted to program that they’d waited on, and they weren’t expecting my film when it showed up, because I submitted very late. So the conversation shifted to that he would love to program the film the following September. I told him that I had submitted to SXSW, and that if I got in that festival, which is in March, I’m not waiting all the way until September for a world premiere, but I would still love to have it play in Toronto.

The conversation shifted to him telling that what I needed to do was to start giving him all the stars and celebrities that could be brought to the TIFF premiere. Ravi directly expressed that that’ll help him make the case for bringing it to TIFF in September. He admitted that the fest really didn’t want me to go to SXSW, that they wanted it to have it as a world premiere, but that he understood, and I should supply that list.

I have emails going back and forth where I’m sending him the list of who I think could potentially get out celebrity-wise I, such as musicians and actors and athletes. But I was very clear in those emails that to me, the stars of the film are the VJs. They don’t get enough credit, and no longer spend time in the limelight. Those were the main people I wanted to see on the red carpet, and in my opinion, that should be enough. I mean, they’ve already been forgotten from pop culture landscape and how much they grew the Canadian music industry.

So, I find out I get in to SXSW, I send Ravi an updated email. And it comes back and I get the tragic news that that he’s passed away. [Srinivasan died unexpectedly of a brain aneurysm in January 2023 at age 37.]

Keep in mind, we had met up for lunch maybe three weeks prior to his passing. After I get an email from another member of the team, I come back to them with what we had been working on, saying, “Hey, see below, these are the conversations I was having,” and encouraged them to see what their lead programmer in Canada was trying to do before he passed away. And then I never heard anything back.

After a while I emailed [TIFF CEO] Cameron Bailey, saying, “Hey man, I was having conversations with Ravi, here’s the thing.” I heard nothing. I find out someone took over and was announced and replaced, to fill in for Ravi. I emailed that person. I again heard nothing.

POV: How did that make you feel?

SM: As long as these individuals are running the festival, I’ll never premiere another movie at TIFF. All I want to do is tell about how much I love WIFF, to be honest with you. They’re rolling out the red carpet, and they’re the only Canadian festival that’s got this because of their passion they’ve shown towards cinema and what I made here.

POV: Just to be clear, it was not an option to do Hot Docs because you had an understanding that you would be doing TIFF?

SM: Yes, I was holding out for the hope for another TIFF premiere. Even before my SXSW premiere, the number one question I’m getting is “When can Canadian audiences see this film?” I kept saying, well, there’s a certain film festival that takes place in our city in September, and that I’d love for the red carpet moment for the VJs and the home audiences to be able to see it then. I kept saying September in our city, and I did an incredible amount of media. The majority of them posted that very [comment]. That’s how they would end the article because local audiences wanted to know how they could see it.

I was down in SXSW, I knew there were a bunch of people from TIFF there, I heard nothing. Then I got accepted into Hot Docs, and I told them flat out that if I accept their invite, does that ruin my chances at TIFF? The told me that, for sure, it does. They said that typically, what you do as a filmmaker is you go back to TIFF and you say, “Hey, Hot Docs has accepted me, I’m thinking about taking this, what do you guys want to do?” So then I did that, and heard nothing. And in waiting, I missed the window for getting in at Hot Docs.

I was sitting there, fuming. Honestly, it’s not about me. I had that great world premiere down in Austin, Texas, and that was awesome. But here, it’s about the VJs! They wanted to know about the premiere as well, about when their family, friends and coworkers could finally see it. I would say over and over that it’s going to be at a big event, with a big red carpet.

I was sitting there, fuming. Honestly, it’s not about me. I had that great world premiere down in Austin, Texas, and that was awesome. But here, it’s about the VJs! They wanted to know about the premiere as well, about when their family, friends and coworkers could finally see it. I would say over and over that it’s going to be at a big event, with a big red carpet.

After we didn’t get into TIFF, I decided, you know what? If the gala event and the dream scenario is to have the VJs is at Roy Thomson Hall, then let’s do it. I picked up the phone and called Roy Thomson Hall, and said this is the film I have, this is what I want to do. They couldn’t have been more excited and more helpful. They also told me, just so you know, that I’m the first filmmaker that’s ever directly booked their venue for a screening.

So I booked our local premiere for the first weekend after TIFF. If anyone asks what is my proudest, happiest moment with the film, it was being there, seeing the amount of media that came out, knowing that we sold that place out, knowing that we came off the back of a film festival that did not have the same amount of fanfare and media and turnout in the seats at that same venue for their big gala events despite their big marketing power.

What sold this film was the connection audiences have to that channel and to those VJs. My shining moment was to see them, to see how happy they were, coming to me with tears in their eyes and telling me how vindicated and celebrated they feel. I have 10 VJs in this film, nine of them were there that night. Unfortunately, Strombo was filming something somewhere else, but he sent very kind words and obviously he’s a big supporter of the project and of my films. We got that great moment, and it was the morning of that premiere that I got an email from Universal Music threatening me with a cease and desist letter.

POV: Oh, dear.

SM: My lawyer told me it felt strange, almost personal. Keep in mind, I had provided Universal Music with a bunch of tickets to the premiere. I was out of promoter tickets at that point, but purchased some at a reduced rate so it still went out of my pocket because they were telling me they were going to bring some legacy artists to the red carpet. Of course, no artists showed up, but their lawyers and [clearance rights] team did. The next morning I heard that they were disagreeing with the law of fair use and fair dealing, and feeling that I should be paying them for the American artists’ music that is featured in this documentary.

POV: What is the current status of that case? You are able to show the film now? Or you’re just showing the film anyway, defying the cease and desist?

SM: No, we never actually got the cease and desist. We got the threat of a cease and desist. The intimidation was, “We will go away if you pay us X amount of licensing,” knowing that that X amount could potentially be less than a lawsuit. That’s wrong, first of all. I’m not the first filmmaker to use fair use, fair dealing—this has been going on for quite a while. I’m insured. I got insured was because I have a fair use opinion letter from Donaldson and Callif, who legitimately wrote the book on fair use in California. That’s the only way that I was able to get insurance, so everything is buttoned up on my end.

Right before I took the stage in Halifax, for example, I got another threat from another record label about paying them money and not agreeing with the law. It’s like, “OK, it’s fine you guys don’t agree with it, but I’m the one following the law, and paying all of the necessary licensed footage. What I’m told I have to.” We also got yet another person coming forward who weighed in, and we didn’t even use their licensing!

As I’m driving to my show in Hamilton, I know some people from the record labels are going to be there with their stopwatches to see how long my license clips are. I went through all my footage with lawyers for six months, and paid an exorbitant fee so that I would be protected. This is the stage that we’re at. I’m not sure why they’re coming after me, but they picked the wrong filmmaker because I’m the guy who put up his house to make this film! I’m the guy who didn’t get into TIFF, and I rented out Roy Thomson Hall. I’m the guy who went to every distributor in this country, and they all laughed at me. Well, they didn’t all laugh, but one did, telling me audiences do not pay money for documentaries, specifically Canadian documentaries, to come to the theatre.

I ended up naively calling every venue. Cineplex [theatres], in my opinion, were too small and lacked the character of what this film is all about, going to see a live show. So I booked concert halls, 14 of them across the country, across five credit cards, with the smallest amount of marketing budget you could ever imagine. I’m shocked every time I show up to a venue and there are hundreds of people there.

To be clear, this is not what I wanted to do. I wanted to go down a very traditional route. I wanted to take advantage of the opportunities in this country for independent filmmakers, via tax credits, via making a successful [prior] film that went on Netflix and then being able to make another one that’s celebrating our Canadian history that Canadian audiences want to hear.

And, Jason, I’ll be honest with you, man, I haven’t talked about it because it’s just starting to happen, but the impact that this film is having in these venues is massive. The ushers don’t leave, they’re locked to the screen. People don’t even go to the washroom.

This film provides such a feel good hit of nostalgia for so many Canadians. It’s frustrating that it had to go this way. I didn’t come here with this master plan trying to be this outlaw filmmaker. I’m trying to follow the rules, but other people don’t, and I don’t know what the reason for that is. I know there’s a lot of politics for things, but to me, screw the politics—you’re making art for an audience and your job as a filmmaker is to entertain them and to make something that you’re passionate about at the same time.

299 is a film I wanted to see that didn’t exist. Why didn’t it exist? Why are these archives not being digitized and captured and celebrated for the ground-breaking journalism that they are? I don’t know, but, all I know is that from a two hour film made with archives, 95% of the footage was sitting unused on original beta tapes that eventually would expire and be gone forever. And now, all of those tapes are being digitized, which is a good thing. Those are the things that get me excited.

POV: MuchMusic is finally digitizing their entire library?

SM: They are. Bell Media is putting forward the necessary resources to digitize the entire thing. And that is because of the success of this film, because it premiered in America and it’s getting all of this international attention. And it’s just interesting to see certain entities, specifically the record labels in this country, want to try to impede it, impact it, or hurt the filmmaker that’s trying to celebrate the very institution that built the up the record industry and the incredible artists. That station was a star making factory in this country.

POV: Where is the film going to end up after your road show?

SM: After the road show, it’s going to be on Crave. The date, I don’t know. The record labels are trying to prevent that, so as of right now, I don’t have an answer to that question of when it’s going to be shown.

POV: So the road show is your theatrical run, basically?

SM: Yes.

POV: Talk about Windsor and what it means to you to have a programming staff or programmer that saw this and fought to show it in Canada?

SM: I mean, to be clear, Hot Docs was the first to accept it and we’re actually now talking about having a second Toronto show at Hot Docs! To be clear, it’s helpful to me any time someone wants to program one of my films and put it in a theatre. Other festivals across the country have reached out as well about trying to program it, but I said no to every single one. I actually said no several times to Vincent Georgie and his other programmers at Windsor. He said, “Hey, let’s just jump on a phone call real quick, just give me five minutes,” and he poured his heart out about how important this film and this story is, and what he’s trying to build there. That five minutes turned into an hour phone call. I was so blown away by a guy who literally sits and watches 600 movies a year, and diverts some of his salary so that he can keep a bigger staff and keep this festival going. His passion came through the phone, and although we’ll be meeting tomorrow for the first time, that blew me away.

It was an opportunity where I believe in what he’s doing, because we’re cut from the same cloth.