In honour of Alanis Obomsawin’s 1984 film Incident at Restigouche screening at Hot Docs, POV has resurrected this interview with the prolific filmmaker from the June 1987 issue of the late Cinema Canada. We thank Cinema Canada for making this interview possible.

***

Alanis Obomsawin has been told that when she was six months old, she was afflicted by a mysterious disease that almost killed her. The night everyone thought she would die, she lay in bed falling into a deep coma. The doctor had said that she wasn’t to be moved or touched. Everyone stood around her, watching helplessly and waiting.

Suddenly, the door swung open, and a great aunt, a very old woman, came in, wrapped up the baby in a big blanket, and carried her off to a little shack on the reserve. Because of their respect for the old woman’s age, the other relatives, although upset, said nothing. “She kept me for six months,” says Obomsawin “Nobody knows what she did to me, but I survived.”

Obomsawin’s mother had brought her to Odanak, the Abenaki reserve northeast of Montreal, just before the illness struck. She was raised in the house of her mother’s sister, Jesse Benedict, and her husband Levi, who had six children of their own. As a child, Alanis had no real sense of the world outside the village that sits just above the St. Francis river – even the village on the opposite shore barely existed. The most vivid memory she has of Odanak is the relationship she had with two old people on the reserve. One of Alanis’s songs begins, “When I was very young, I had two friends – my old aunt Alanis, and my mother’s cousin Theophile Panadis. Myoid aunt Alanis, she was beautiful. She made baskets, and she loved me. Theo would tell me the Abenaki history.”

When Alanis talks about her childhood, her sensuous memory conjures up all the Sights, sounds, and smells that she experienced. “In those days,” she says, “everybody made baskets and canoes. They worked with the wood from many trees – especially the ash, spruce, birch, and pine – and sweetgrass was an important part of everyone’s daily life. There wasn’t one house you could go to that didn’t have those smells. I realized that much later in my life because I missed it so much.” She also misses the sight of people sitting in straight-backed chairs, braiding the sweetgrass and weaving the baskets. Everywhere you looked were brilliantly colored ashwood splints, curling like ribbons on strings overhead. When she was small, Alanis liked to squeeze into the chicken coop while the hens were laying eggs. Everybody told her not to do it, that she would upset the chickens and make them jittery. But Alanis swears that no matter how close she got to the hens to hear their cooing and clucking sounds, they remained perfectly calm. Today, she might suddenly lower her voice, do an imitation of the sounds, and break into a hoarse laugh because performing the hen imitation makes her cough.

Alanis has never, throughout her life, and despite many attempts to force her, eaten meat. “Animals,” she says “have histories just like us. They know their friends, and they know their enemies.” When you watch the films she’s made, you notice how often images of animals, birds, and fish appear in them – images like the salmon that flash, or pulsate in slow motion, across the screen in _Incident at Restigouche_,

When Alanis left Odanak to live with her parents in Trois-Rivières, life became very different. She was now the only Indian child in the entire town, unable to speak French fluently, and she had to “survive a lot of things that are not so nice to think about,” No matter which route she took home from school, she was systematically beaten up by her schoolmates. Alanis has never forgotten Mlle. Reault, the teacher who twisted her long crimson fingernails into her arm and called her a ‘sauvagesse.” Alanis also had to suffer through Canadian history classes, which always seemed to be about martyred priests being tortured to death by Indians. It wasn’t until her father died, when she was 12, that she began to rebel against the prejudice and racism. “As I grew older,” she says, “I was always made to feel that I should be selling myself, or that I should be someone’s maid, but I always found a way to,fight back.”

Ironically, in the eyes of the federal government, Alanis was not officially an Indian, and eventually, she fully realized what it meant to be’non-registered’. As she points out, “I never had any rights. But you see, when you’re young, you don’t grasp that. I never knew that story – registered or not registered – all I knew was that 1 was an Indian, and that was that. It’s much later that it all came out, and I realized the racism and prejudice that can exist even amongst your own people. That’s probably the hardest thing to live through – to feel those kinds of things.”

At the age of 22, Alanis left Trois-Rivières for a two-week trip to Florida that turned into two years of taking care of children, modelling bathing suits, and learning to speak English. After she moved to Montreal in the late ’50s, she became part ofa circle of writers, photographers, and artists that included Leonard Cohen, Robert Herschorn, Vittorio, Derek May, John Max, and many others. (Ask Alanis if she was the inspiration for Catherine Tekawitha, the mythic heroine of ‘Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, and she might laugh, “Ask Leonard.”) About that circle, she says, “We were friends. They were very cultured people, and I learned a lot from them, their way of being. Lots of good times. Lots of singing.”

Gradually, she began to emerge as a singer (first professional engagement: Town Hall in New York City) and a storyteller, who was specially interested in giving young children a concrete and meaningful sense of her people. In 1965, a CBC Telescope program about Alanis caught the eye of Wolf Koenig and Bob Verrall, two NFB producers who invited her to consult on several projects.

At the Board, she began making her own films, and she devised multimedia educational kits that are ingenious microcosms of the Manowan and L’Ilawat tribes. She has also appeared in many other people’s films, among them, Kathleen Shannon’s Our Dear Sisters and Gordon Sheppard’s Eliza’s Horoscope. All these years, she has continued her singing career, appeared frequently on Sesame Street, and in 1983, she was awarded the Order of Canada for her contribution to native rights.

Alanis Obomsawin lives with her 17-year-old daughter, Kisos, in downtown Montreal. The 19th-century townhouse they share is filled with paintings, photographs, pastels, and lace. The kitchen, which is the focal point of the house, makes you feel you’re in the country with its wood-burning stove and long refectory table. When Kisos was a small child, Alanis, in the tradition of her people, took her daughter everywhere – even to work. “Our people have always worked and had their children with them,” Alanis says. “Here, people make a separation, but I never allowed it. I guess I was the scandal of the Film Board, because I seemed to have raised Kisos there, but I don’t think it damaged anybody; on the contrary, I think it was good for them.”

Today, the Film Board provides day care, and Kisos is a pretty and lively teenage girl, who says she’s into being ‘alternative’ and dreams about travelling to Spain and the Fiji Islands. She has little interest in her mother’s work, or her causes. “She ignores a lot of the things I do or say,” says Alanis without any trace of disappointment. “She has things of her own that I have to respect, and it will be later, perhaps only when I’m dead, that Kisos is going say, ‘Oh, my God, my mother was like this.’ I know that in advance, and that’s her time, that’s her life.”

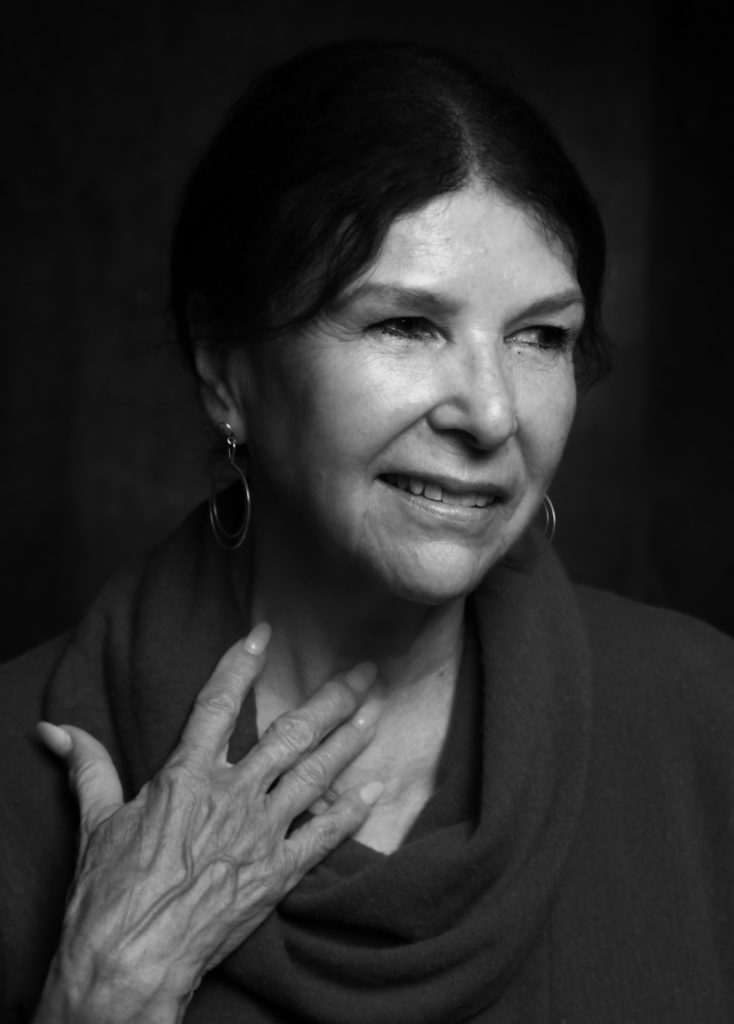

Alanis is the kind of person who seems totally in possession of herself. Every movement she makes – whether she’s threading film on a Steenbeck or spending hours cooking one of her spicy, sensuous meals – is gracious and elegant. You can sometimes feel daunted by the strength of her presence, or by an apparent aloofness, but a moment later, you are bathing in her warmth and humor. She’s entirely in touch with Montreal and the rest of the world outside Odanak, but that tiny village and the Abenaki tribe (the word lJIeans ‘people of sunrise’) are the continual sources of all her strength. “I have a drive,” she tells you, “from every bit of memory I have from my childhood.”

At this point in what Alanis would call the “long walk” that is her life, she feels “I have come to a time now – it was very, very hard at the beginning – that I have developed my own way of standing on my two feet no matter where I am, and being part of our culture, and carrying it with me. I think I bring it to other people who meet me; I bring them something.”

The Films

For Alanis Obomsawin, film is what she calls a “bridge,” or a “place” where native people can talk to each other, and to us, about their losses, their memories of injustice, their desire to share what is good about their way of life, and with that sharing, become strong. We have a sense of filmmaker who is a listener and a compassionate observer, like John Grierson, Alanis believes that film must attempt to transform people, even to the point of causing social reform.

In a calm, measured tone (using precise narration she always writes and speaks herself), Alanis constructs clear filmic statements. Although style and form are secondary to her, the films are filled with flashes of visual poetry. One also becomes aware of certain patternsthe consistent sense of paintings and drawings; images of nature, and the music that is woven into the texture of her films.

Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), her first film, introduces us to a remote Cree village on James Bay. Not only is this one of the first Canadian fllms to portray native life through the eyes of Indians, the entire film tells us about life in Moose Factory through the drawings and paintings of its children. The artwork springs magically to life because as we’re looking at houses and clotheslines, portraits of families, or fairy tale images of a black bear in a luminous blue forest, and an “Indian angel,” we hear the village’s dogs, the wind rushing through the pines, and the voices of Moose Factory’s children on the film ‘s soundtrack. The kids talk about ordinary details of everyday life; they tell a story about being frightened by a bear; they fantasize about Christmas. The film is full of surprising juxtapositions of color – deep blues, purples, and bursts of red – and we see nothing but the drawings until the end, when a montage of stills shows us the children we’ve been hearing, Moose Factory cuts through many of the stereotypes of native people, suggesting how they are both like white people and somehow different.

Mother of Many Children (1977) travels across the country, introducing us to girls and women from many different tribes. It takes us from the puberty rites of adolescent girls to a portrait of a 108-year-old Cree woman called Agatha Marie Goodine. We watch women who are still in touch with ways of life that revolve around the land and water – rocking their babies, ice-fishing, gathering wild rice, hooking carpets and carving images out of stone. Alanis also shows us the experiences of the first native woman who worked at Indian Affairs, a young student at Harvard, and women who have been badly hurt by city life. One woman on Winnipeg’s skid row tells us that eventually a prison cell becomes so much a home, she feels sad when she leaves it.

Near the end of Mother of Many Children, Agatha Marie Goodine takes a walk down a tree-lined country path. The old woman, wearing a blue print dress, and encircled by an obviously affectionate group of boys and girls, moves determinedly through the warm summer air, talking about Cree beliefs, telling stories, and cracking jokes about how ridiculous it is to be crippled by age. From time to time, she rocks her torso and gestures with her arms in a way that startles you with the sudden feeling you’re seeing a vision, a full-bodied apparition from the past. You know that as fast as the film you’re watching is unreeling, the particular expressions on that creviced face, the rhythms of that voice, the mysteriously expressive movements of those arms, that kind of being in such a pure form, are becoming memories. “Life was so beautiful then,” the old woman says to the children, and to the film’s audience, ‘‘we thought it would go on forever.”

Amisk (1977) shows the viewer the richness and variety ofIndian music and dance. In the ’70s, the Cree way of life in James Bay was being threatened by the Quebec government’s mammoth hydroelectric project. Reacting to the threat, Alanis and some other people organized a festival to give support to the people of James Bay. For a week, performers from many different tribes in both Canada and the U.S. – including Inuit people, Metis, Sioux, Ojibway and Dogrib – sang and danced in halls and clubs all over Montreal. The climactic event of the festival was a concert in Place des Arts, which Amisk documents.

When people, who have little exposure to native music, see this film for the first time, they are stunned by the excitingly unfamiliar rhythms and sounds that have been on their doorstep all their lives. Hoop dancers spin across the stage; the Dogrib churn to the beat of their drums; Alanis herself, dressed in bright red, sings a lullaby, and Willie Dunn gives a passionate performance of his Buffalo Song. At one point, two Inuit women in parkas stand almost mouth to mouth calling to each other in the strange, guttural, intersecting sounds of a throat song.

Amisk is not only a concert film. Intercut with the performances is footage of the Cree people of Mistassini talking about the kind of loss that provoked the making of the film. One man says that he could once get all the meat he, his family, and many of his friends needed for the price of ammunition. The same meat, in a store, would cost $1,000. Once there was the land, which was the source of life. Now there is a store.

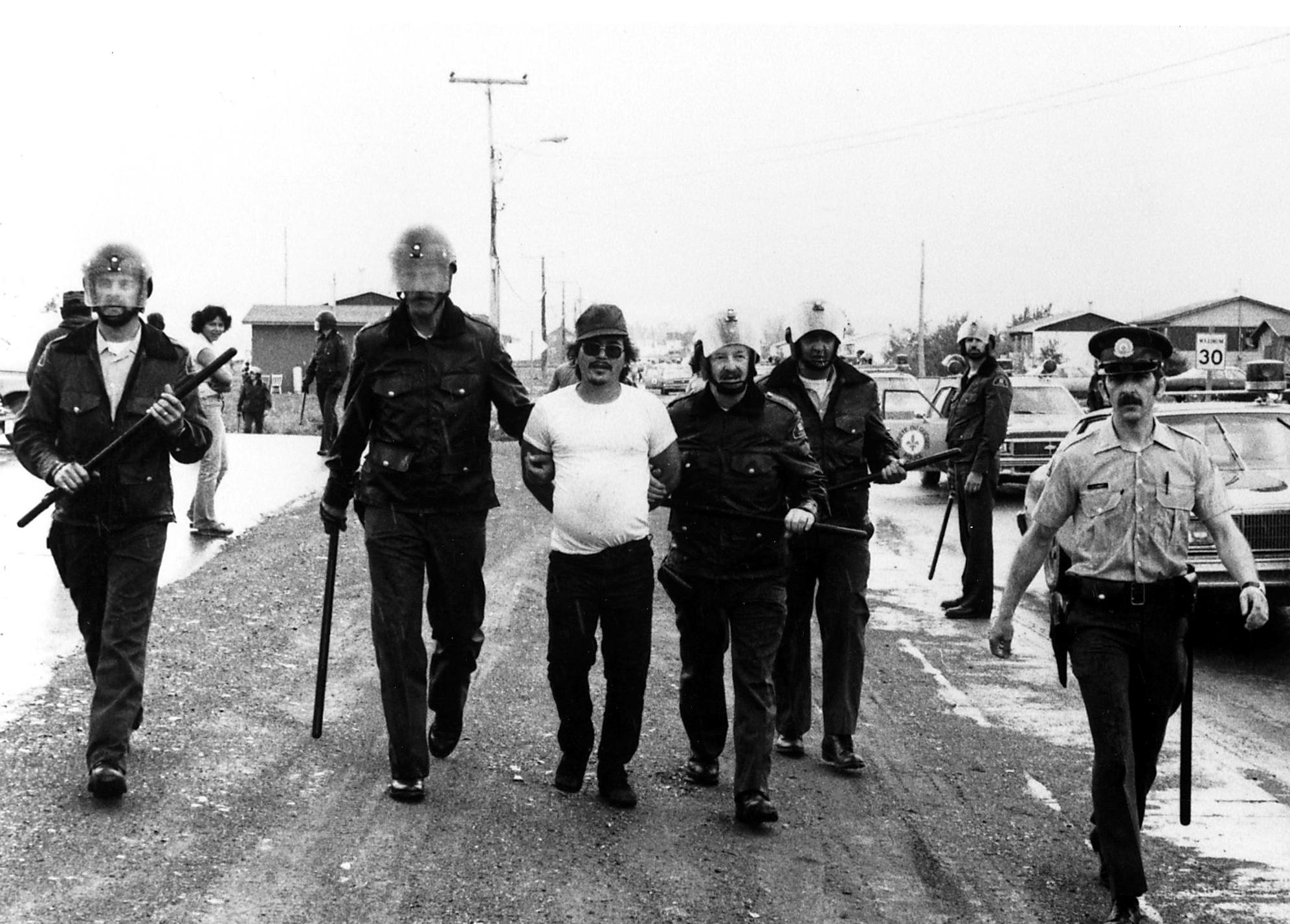

Incident at Restigouche (1984) demonstrates how a conflict between people and government can tum into grotesque theatre of the absurd. In June, 1981, a virtual batallion of 550 Quebec Provincial Police (QPP), in full riot regalia, marched into the Micmac reserve on the Restigouche River and announced, “We are taking over today, and we are the bosses now.” The announcement was followed by volleys of racist invective, swinging clubs, and a number of arrests. The crime? The Quebec Ministry of Fisheries had come to the conclusion that the handful of Micmac salmon fishermen living on the reserve had exceeded their quotas. Despite the insults, the beatings, the fundamental injustice of the QPP’s preposterous invasion, many of the native people we meet in the film show the good grace of seeing the painful humor in the situation. A young couple smiles wryly as they talk about the problems you can have getting to your wedding reception when 550 cops have invaded your village. Alanis points out, “The basic argument of the film is that Indians have rights, and you have to respect those rights. They are the owners ofthis country-whether anybody wants to admit it or not – and there are a lot of people here not paying their rent.”

A postscript. Since the completion of Restigouche, Lucien Lessard, the Quebec minister of Fisheries at the time of the incident, was arrested for fishing without a license. He was eventually acquitted on the basis of his lawyer’s argument that the Quebec fishing law is not well enough defined.

At the end of the film, a harmonica wails as a crow, the messenger bird, takes flight. “I think that Richard speaks very well for himself,” says Alanis. “Nobody has to be told ‘It’s your fault’, or’it’s not your fault.’ His gesture is strong enough. For me, the film is for all people concerned with children – any children. I want people, who look at the film, to have a different attitude next time they meet what is called a problem child, and develop some love and some relationship to the child – instead of alienating him. I want even the worst person, who makes problems for children, to go home and change some of his rules and attitudes.”

Poundmaker’s Lodge: A Healing Place (1987) is in the final stages of production. Near the beginning of the film, the camera pans from a busy Edmonton expressway to a body lying in a heap of rubble under a bridge. Near the end of Poundmaker, the camera climbs slowly up the walls of a teepee toward streams of sunlight at the top. In between these two images, we find out about a place in the countryside, not far from Edmonton, called Poundmaker’s Lodge. At the lodge, native people addicted to drugs and alcohol get a chance to release themselves from their demons. “You feel so warm when you’re going up,” sings Shannon Two Feathers on the film’s soundtrack, “So cold when you’re coming down.”

Alanis calls the lodge “a healing place” since “to go there is to go home,” back to the love, traditions, and religious ceremonies of the past. Various forms of therapy, Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, and physical exercises are available, but Poundmaker’s Lodge is unique because elders and medicine men are an integral part of the process, helping people return to traditions that are thousands of years old. “They were good for the past and are good now. This is what people have lacked and why the lodge works.”

In the late ’70s, Alanis collaborated with the Council of Ministers of Education, on a series of school telecasts, called Sounds from Our People. These half-hour programs, broadcast on the CBC, include “special adaptations” of Amisk, Mother of Many Children, Martin Defalco’s Cold Journey, Tony Ianzelo’s Cree Ways, and two projects Alanis shot for the series: Old Crow and Gabriel Goes to the City. She has plans to release these works as completed films.

The Conversation

Cinema Canada: How do you see the purpose of your films?

Alanis Obomsawin: The basic purpose is for our people to have a voice. To be heard is the important thing, no matter what it is that we’re talking about – whether it has to do with having our existence recognized, or whether it has to do with speaking about our values, our survival, our beliefs, that we belong to something that is beautiful, that it’s O.K to be an Indian, to be a native person of this country. I don’t want to say that we’re better than anyone else, but as good. And that we have a lot to offer this society. But we also have to look at the bad stuff, and what has happened to us, and why it’s happened. We cannot do this without going through the past, and watching ourselves and analyzing ourselves, because we’re carrying a pain that is 400 years old. We don’t carry just our everyday pain. We’re carrying the pain of our fathers, our mothers, our grandfathers, our grandmothers – it’s part of this land. It’s going to take a long time for us to become ourselves again. The films are for that purpose.

Cinema Canada: Many filmmakers have been drawn to the medium by the work of certain great directors, by stylistic approaches, or by particular movements in filmmaking. Who or what was your inspiration?

Alanis Obomsawin: My inspiration came from my own people, from their urgent need to have a place to speak. For me, film is just another form, like my singing. It’s the same thing because I sing about what’s happening to us politically, what’s happening on the streets, what’s happening to the women, what’s happening to the children.

Cinema Canada: Can you think of a scene, an image, a moment from a film that does what you think film should do?

Alanis Obomsawin: I appreciate a lot of films. Once I was looking at Yves Dion’s La Sourditude, which is about deaf people, and to this day, I have not forgotten it. In the film, there is a dance in a huge, huge hall, and it’s like a silent party. The people are laughing, they’re happy, they’re drinking. A beautiful girl is standing on a stage with a record player behind her. Edith Piaf is singing ‘La Vie en rose’ (“Quand il me prends dans ses bras … “), and the girl is miming – not just the words, but the feelings of the song. It is the most moving scene. You see all those people with their eyes, just looking up at this girl, who – with her signs and her tenderness – is just so beautiful. You watch that, and you really think about human feelings and human communication. It is a marriage of what real feelings are about, no matter how dispossessed you are. It made me feel good, because this film was made at the Board. I think the whole world should see it. Does everyone know how sensitive Yves Dion was to make that film?

There are many other films made at a the Board that are documents, which will have a life long after the fiImmakers are gone and serve many generations to come. I think of such films as Donald Brittain’s The Champions, Martin Duckworth’s Return to Dresden, the productions of Studio D, and the animation studios. In Return to Dresden, one of the men who bombed Dresden says to a woman, whose children were all killed in the raids, “We have to create a world in which orders of that kind like firebombing cities are not given any more.” Martin has made a film that goes beyond the usual feelings about peace and war.

Cinema Canada: What excites you most about filmmaking?

Alanis Obomsawin: I think the power of the medium is certainly very important. I also feel I am constantly learning, and that is very exciting to me. But the thing I like best about film is the excitementof meeting the people. There’s a lot of beautiful things that happen in making a film – for instance to see, no matter what people have gone through, their will to live. I think that’s the part I find most exciting. It doesn’t matter where I go – whether it’s our west or up north – when I’m going to a native person, I’m always going home. I would never even stop going to prisons, and skid row, where you find a high percentage of our people. You watch the drinking, the people sleeping on the sidewalks, being abused, and you hear terrible language. It’s a snake pit. But I cannot divorce myself from them. There was a time in my life when I was told that’s where I should be. I fought back and fought back. That’s why I understand and love all the people down there. They’re not separate from me.

Cinema Canada: Tantoo Cardinal (Rosanne in Anne Wheeler’s Loyalties) has said similar things about herself.

Alanis Obomsawin: She’s really a special person. And there’s lots of people that somehow have managed to be strong and do something. I don’t mean to say that the people who are down there on the street are not strong. But how much can you take and how long do you go on until you finally believe what they’re telling you: that you’re no good, that your parents are no good, that your language is no good, that you don’t have a culture, that you don’t belong. You see your parents, who are drinking, who are in a terrible state. And you look in the mirror, and you don’t like what you see, so you end up fighting your own people, killing each other. And it took me many, many years before I could understand that. And today, I understand it – not that it’s less painful. It’s very painful to look right in the mirror and say “No I’m not ugly; my parents are not ugly” – when I say ugly, I mean inside, spiritually, your soul, yourself.

Cinema Canada: In many of your films, people are talking very intimately about the way they live. How you do you approach the interviews?

Alanis Obomsawin: I go to the locations on my own for several weeks, and I don’t go only once. I spend a lot of time with the people, telling them what I’m trying to do, and asking their advice. We converse and see if we are on the same level, because in my mind, I’m not the only one making the film; it’s many people, and they are the most important part of the film. I look up to them. In 99 per cent of the cases, the interviews are very private. They are between me and one particular person. And the reason why we are able to converse that way is because we come from the same place, and there is an automatic understanding. I might ask them to repeat certain things on camera, when the crew arrives, but a lot of things they wouldn’t say on camera, or in front of another person, because it is too difficult. This is why I use a lot of voice-over. I really like that process. The feelings and the emotions really come through even though you don’t always see the person’s face right on camera.

Cinema Canada: How do you choose the material you’re going to shoot for the voice-over?

Alanis Obomsawin: It depends on what’s there. I go by the surroundings of the people I’m talking to and what they do. I make sure I cover myself.

Cinema Canada: Since your first film, you’ve had a tendency to begin a project by recording sound before you start shooting.

Alanis Obomsawin: I come from a culture of storytelling, and I’m used to listening to people speak. For me, every human story, every life matters. I’m interested in everyone’s life – what they’ve gone through, how they live, how they feel, how their spirits are. And I don’t cease to be excited about that. And I think the sound of the voice is very, very important to me. Of course, I love the image, but the voice is very important. I make sure I record whatever natural sounds the people hear locally – the bush, the animals, the music, the songs. I take particular care of music in all the films. When I’m on location, I always look for the performers, because I like to hear their music and have their presence in the films.

Cinema Canada: Do native people work on your films in other ways?

Alanis Obomsawin: All my assistants are always natives of the area I fought very hard for that from the beginning. Once, we brought a young guy, called Louis Echaquan, to Montreal, and we trained him as a professional soundman. He worked on many of my projects – thank Go I had him on Mother of Many Children. With Richard Cardinal, I had Richard’s brother, Charlie, for a large part of the shooting. He could draw, so we made a storyboard for the shots that re-created Richard’s early life. Charlie came with me to most of the locations before the shoot and talked to me about how it was and where things happened. I would love to have an Indian crew – that’s for sure. But of course, there are also Film Board people that I like to work with.

Cinema Canada: What have your 18 years at the Film Board been like for you?

Alanis Obomsawin: Right now, it is very good for me because I get encouragement from the people at the Board. I’ve had good feelings in the last few years. It’s wonderful to have that feeling there’s confidence in what you’re doing. Marrin Canell and Bob Verrall were producers with me on Richard Cardinal and Poundmaker’s Lodge, and they were very helpful. I did not have to raise the money for these films either. It’s much better for my morale and for my work if l don’t have to fight so much, find the money, get this and that, get permission to go somewhere to do the work. All that can take so much energy, a lot of hours and a lot of days. There are individuals, who have made my life difficult at the Board, but they are not the Board. Also, there are a lot of wonderful people, whose names you never see on films. There’s Claude Chevalier in sound, Gudrun Kanz in the lab, Gilles Tremblay in animation camera, and Jimmy Bell in traffic control. These are people who know their craft and are willing to share their knowledge, and that’s what the Film Board is all about. It’s not a school in the sense that you go there, and they’re going to show you how to make films. I wasn’t assisted that way. But I could go to individual people and ask, “Could you show me how to do this?” Over the years, even if I was in trouble, there were always people I could go to.

Cinema Canada: When you did have to find money for your other films, how did you do it?

Alanis Obomsawin: The hard way: standing up in a canoe.

Cinema Canada: Before you began Mother of Many Children, some people felt it should be a film about famous native women.

Alanis Obomsawin: I myself wanted to pay homage to women at home, who survive, who take care of children – people that you don’t really know. I wanted to show the beginning of life to the end through as many women as I could – in terms of culture, traditions, and language. But to get the money was a different story. There was going to be no film. I have letters saying “Forget it.” Indian Affairs doesn’t want to put money into it; they don’t want a film on women, and the Film Board wouldn’t give me any money to make the film unless I got money from outside. At one point, I gave up. Finally, I thought that’s crazy; I’ve spent my energy on this, and I’m going to do it.

I got up one morning; I took a train to Ottawa, and I went from office to office, until I came back with money from the Secretary of State. I started doing one sequence, and from there, I begged for money for the next one, and that’s how it went. But if it hadn’t been for all that, there would be no such film. After the film was finished, I got a letter from the Secretary of State saying that they had never invested their money in a better way in any film up to that time. And the man in charge of Indian Affairs also wrote me a fantastic letter.

Cinema Canada: You told us that you heard about the first Quebec Provincial Police raid on the Restigouche reserve from broadcasts and friends, and you wanted to go into action immediately. What prevented you from doing so?

Alanis Obomsawin: When I heard what was going on, I said, I have to get there. But to get there was a big problem, because there was no money at the Board. Finally, when I was ready to go on my own, I was given a bit of money and some equipment. I went and did a lot of interviews, but that was only after the second raid. I wasn’t there during the raids at all – that material in the film came from the CBC, L’Aviron (a newspaper in Campbelton), and a freelance photographer who was there at the time. I would have been there for the second raid, at least, if I had gone when I wanted to. But, you see, that’s the problem for many documentary filmmakers, including those at the Board. When there’s something important happening, there’s no way of getting there fast. I wish I had a budget to cover such events so that when something is on, I can go immediately with a crew. Restigouche would have been a very different film if I had been able to start shooting when I wanted to.

Cinema Canada: Once the shooting started, did things get easier?

Alanis Obomsawin: I had a very hard time making that film. My history at the Board has not been easy; it’s been pretty painful. It’s been a long walk. Racism and prejudice exist there like anywhere else. When I went to the program committee to get funds to continue the film, I told them I wanted to interview the Quebec Minister of Fisheries, and I had more interviews to do back at Restigouche. And someone said, “Well, I don’t think you should interview the whites.” I could have gotten into a big fight right there, but I chose to say nothing. And, of course, I did the interviews that I wanted to do, and I interviewed Lessard myself When I came back, we had to go back to the program committee for finishing money, and the same member said, “Well, Alanis, I thought we told you not to interview the whites.” And then I jumped on this person. “Now I’m going to tell you how I feel,” I said. “I know you told me that, but you or nobody is going to tell me who I’m going to interview, or not interview. And if you feel that I, as a Native person, cannot interview white people, we’ll go through everything the Film Board has done with Native people, and see who interviewed them. And I’ll tell you something else, not you, nor any other person could have faced the Minister the way I did. You’ve got a long walk to do before you can do that.”

Cinema Canada: Your interview in Restigouche with Lessard, the minister of Fisheries, is one of the strongest we’ve ever seen in documentary. The audience really feels your anger.

Alanis Obomsawin: Anger? I was furious. Anger is too polite. But I admire him for having the guts to come here from the Côté Nord when I said I wanted to interview him on the subject, and I respect him. Whatever it was that he did that appalled me, he faced it. Of course, I fought with him the whole time. I stuck to my guns, and he stuck to his, but I admire somebody like that. I was so mad at him. I was in Restigouche the time that he finally came to speak to the people after the second raid. The things he said were so totally racist. And during the raids Lessard ordered, the cops shouted at the Micmac, “Maudit sauvage, you fucking Indian, you fucking savage.” When you hear that, you ask, “Who are the real savages?” I’m not saying that the Micmac were angels. But you know, with 550 policemen there, I think they behaved in a way that was more than dignified. And to have the children watch that! It’s not something that people are going to forget.

Cinema Canada: After the various problems you encountered making Restigouche, what was the final reaction to it at the Film Board?

Alanis Obomsawin: Toward the end, Peter Katadotis, director of English production, saw how far I had gone, and he was very excited. At the end, he really liked the film, and he told me so.

Cinema Canada: Why is it that, except for the educational programs that were broadcast on the CBC, none of your films have been shown on the network?

Alanis Obomsawin: I cannot speak for the CBC. I could say it’s prejudice, it’s racism, or it is because of the language, because people have an accent, because it’s all Native people, because the CBC did not do the film themselves, or maybe because a Native person did them? It could be any of those things, and it could be none of them, or it could be all of them. I don’t know. And I don’t really care. I’m going to continue making films. If any of them ever appear on the CBC, I’ll be grateful, but I’m not going to change my way of making films. The films are in constant use by Native people, for schools, universities, and people all over the world, who want to find out about us.

Cinema Canada: In Richard Cardinal, you use docu-drama for the first time. Will you be doing more in the future?

Alanis Obomsawin: I love drama but I don’t think I would ever march away from documentaries, because that is the only place that people have a voice – a real voice, the real people. It doesn’t matter what background you come from. But I think it is very important for people to have a voice – directly, not only through drama or reenactment, which also has its value. I think documentaries must survive, and I think they will. I have no doubts in my mind.

Cinema Canada: Some people think that the Film Board, for many years now, has been abandoning documentary and self-destructing.

Alanis Obomsawin: Yes, some people have said that. A lot of people say things when they don’t really know what they’re talking about. Many people outside say things about the Board that are such lies. Some independent producers and filmmakers, who are criticizing the Board, are sucking hundreds of thousands of dollars out of it at the very same time. It is pretty dishonest, I think. And all those people that are now on their own, and doing well – how many of them have been trained at the Board? A lot.

Someone said to me the other day that you have to give François Macerola credit for all the time he spends in Ottawa really talking to all the politicians and trying to save the Board. That is something to look up to.

Cinema Canada: What would you do if you were head of the Film Board?

Alanis Obomsawin: I would do my rounds. I would go into the cutting rooms; I would speak to producers, and I would speak to filmmakers. And if somebody has a problem, I would go to their place of work. I think that would make a big change and create an atmosphere of goodwill. People would talk and argue things out. And I would tell my problems to the filmmakers, the pressures that are on me, and the things that are impossible. I would keep them informed. Then we could fight for certain things together.

I think that the head ofthe Film Board has no real power. The power lies in the films that come out of the Board. Despite the demoralization of the filmmakers over the past few years, people kept on working and made an unbelievable number of good films. Also, the number of co-productions and the assistance to outside filmmakers to finish their films is very high. I would certainly speak up, and do my best to make people feel good about what they’re doing. The Board is the voice of the country – people sometimes forget this. If they were to lose it, I wonder who would nourish the public as the Film Board has all these years. They make films that could not be made anywhere else. Who would allow the people to tell their stories?

The Dream

Alanis’s dream world has always been a refuge and a vital part of her life.

It is so beautiful this horse, and the colour of the green is not like any green I know in this lifetime. It’s so special. The horse doesn’t look exactly like a horse that we know in this life. It has a different look. The horse is constantly following me to the point that I get very tired of him, and he grabs me, and he talks. I am always running away from him until I make a deal with him that if he stops running after me and grabbing me, I will be his friend and come to visit him.

He says, “Yes, but how willI know?” And I say, ‘‘You will know by the way I touch you.”

Finally, when we agree, I come out of the house that I am locked into, because I don’t want him to grab me. There is somebody inside that can grab me too – a terrible situation. And then he gives me a bouquet of flowers. The flowers that he gives me are very tiny, but the colours are very much like the colours of the splints my people used to weave into baskets. Very strong colors – many, many of them. Some real red. Good red. Purple, yellow, navy blue, so many colours that I don’t even see anymore, and new colours that you don’t regularly see in a lifetime. And then we walk down the road, and the sun is shining just like gold following us. There’s a very good feeling between the horse and me.