POV is pleased to be publishing Poh Si Teng’s incisive keynote address to the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, which is still taking place this week. Poh’s speech covers many of the concerns facing the documentary community internationally. As such, her words should be of interest to POV’s readership. Poh Si Teng is the Executive Editorial Producer for ABC News Studios at Disney. She is an award-winning documentary producer and journalist, whose credit includes the Oscar nominated St. Louis Superman. She was formerly the director of IDA Funds and the Enterprise Program, and the documentary commissioner overseeing Canada, US, and Latin America for Witness-Al Jazeera English.

—Poh Si Teng and Marc Glassman

***

Good evening.

It’s such an honor to be here with you to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival.

When Rachel Gregg, the head of Big Sky, asked me to deliver this year’s inaugural keynote, I jumped at the opportunity. I thought to myself, what a fantastic way to start the new year: amid the majesty of the Rocky Mountains in Missoula, the ancestral territory of the Salish, Kootenai and Kalispel people.

To be in the company of friends and storytellers, and a little removed from the geographical and conventional centers of documentary.

Whether we’re filmmakers or industry gatekeepers, we know this to be true. Some years are hard, some prosperous, and some years we have to pause and assess, and think about how to grow differently.

We’re only a month and a half into 2023, so it’s hard to predict what the rest of the year will hold.

But we do know this: There have been massive cuts across our nonfiction industry and documentary field, and it is directly impacting independent filmmakers.

At times like these, it’s worth taking a pause to think about what success means. For most, it’s about being sustainable.

What I’ve noticed is that something is affecting everyone.

It is the pressure to “succeed” and emulate those who seem to be “getting ahead.” This is true for so many–myself included.

Exacerbated by social media and a broken awards system, we are forced to create unrealistic expectations of ourselves, which is disheartening when we can clearly see shrinking investments across our documentary field.

So how should we proceed?

I don’t presume to have the definitive answer.

But I’ve tried a couple of things that have helped me find some degree of artistic sustainability.

Take a long view of nonfiction storytelling.

THIS IS A LONG GAME.

If we are to have a chance at an enduring career in filmmaking, then we have to potentially make different types of films, be open to different types of distribution, and, lastly, be honest with ourselves — and the people in our films — about what is actually possible at the moment.

Some stories, we are told, “do well,” some are “too niche,” some “too general,” some “not commercial enough”… We know how long that list runs.

In the past 20 years, I’ve had the privilege of wearing different hats in nonfiction storytelling: as a print journalist, a cameraperson, an independent director and producer, a documentary commissioner, a grantmaker, and now a studio executive.

Having worked on a variety of documentary films and in different capacities, I’ve learned this: You can only tell a story in your way. Everything else is just mirroring.

Some films are just meant for the filmmaker – as acts of expression and self-actualization for the storyteller.

Nearly two decades ago, I had run out of options to stay in the United States as a foreign student. After undergraduate journalism school, though, I landed my first full-time job as a cameraperson for a wire service and I was based in Miami. In that position, I was busy chasing breaking news – filming celebrities and DEA drug busts in Florida.

But I didn’t want to be a newswire cameraperson; I wanted to make

documentaries. But I also wanted to stay in America and I couldn’t afford film school. We all do what we need to do to pay the bills.

I returned to Malaysia, the country where I’m from, and received a grant to direct my first documentary: Pecah Lobang, or Busted, about Muslim transgender women who were sex workers in the capital, Kuala Lumpur.

As ethnic Chinese, a minoritized group in Malaysia, I had often felt discriminated against by the country’s divisive politics that ostensibly favored the predominant ethnic group. And so making this film was my opportunity to interrogate my biases, and to recognize that politics of division hurt everyone including those minoritized within the majority community.

For that film, I was the director, producer, cameraperson and editor.

I made no money; in fact I put in a lot of my own savings. It was my film, so it didn’t matter.

It was a test for myself, on whether I could actually make a character-driven observational film, that I could be more than a newswire cameraperson.

That little film, I made for myself. I had zero connections in the documentary field, and the distribution was very DIY. The film Pecah Lobang ended up receiving a local award in Malaysia, and had its international premiere at the Frameline Festival in San Francisco.

That was enough success for me, for my first film. Of course, everyone likes awards, money, articles, and being interviewed, but it’s also OK to not want any of those.

Then there are films that are meant to advance crucial conversations within our communities.

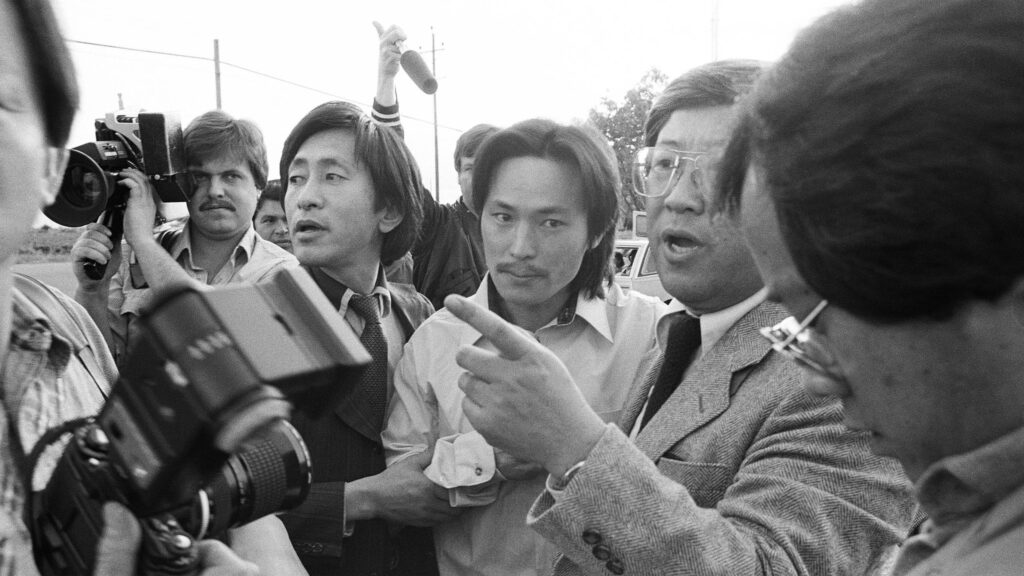

When I think about recent films that are beautiful tributes to community, I think of

Eugene Yi and Julie Ha’s Free Chol Soo Lee, and Nausheen Dadabhoy’s An Act of Worship.

An Act of Worship explores 30 years of American history through the perspective of Muslims across the US who have lived it.

I’ll be honest, when I first heard the pitch as a documentary commissioner, I couldn’t understand how the seemingly disparate, multiple layers would come together. It all sounded like a lot.

I remember at a Hot Docs Forum, wearing the hat of a commissioning editor, I told Nausheen there needs to be a strong throughline to bring all the different parts together, so that it resonates with a broader audience.

Nausheen replied that she was making the film for herself and her community, and not for a broader audience.

That was a teachable moment for me. I ended up supporting the film through a grant. And when I eventually saw the completed film with my Muslim American friends at Tribeca last year, I was floored.

There is a very important place for films by and for community that are not necessarily to educate or to entertain the broader public. If you want to make a film for your people, you should. Yes, even if commissioning editors think it’s too narrow.

My dear friend, Natalie Bullock Brown, filmmaker and a field leader from the Documentary Accountability Working Group, recently pointed me to Black filmmakers and writers such as the legendary Zora Neale Hurston who documented segregation in the early 1900s.

They are reminders that for as long as communities have been around, filmmakers and creatives have always been making art and speaking to the moment. That work continues to offer us strength and inspiration when many of us find ourselves struggling.

We are still discovering films that were made a hundred years ago. A cursory glance at Maya Cade’s incredible Black Film Archive has changed what I know about film history.

So, make a film even if you can’t imagine what your audience looks like. Make it for whoever you think needs to see it.

Zora Neale Hurston’s films didn’t premiere on prime time, but they’ve found their way into our psyche, our learning, our worlds.

They form the spine of Margaret Brown’s Descendant, and there’s a new PBS documentary about her called Zora Neale Hurston: Claiming A Space, by Tracy Heather Strain.

There is endless profundity in legacy and in intergenerational wisdom.

But I get it. Some films need to speak to the immediate moment and a broad audience.

The example I’d like to share is a film that had its world premiere here at Big Sky, a short documentary that I produced called St. Louis Superman.

The film is about activist and battle rapper Bruce Franks Jr., who was voted into an overwhelmingly white and Republican Missouri State House. It’s about Bruce overcoming both personal trauma and political obstacles.

That film we made for ourselves – for Bruce and for the team: directors Smriti Mundhra and Sami Khan. We made it for the public, for a broadcaster that didn’t care about commercial success.

It was a special journey, in which we found each other. And everyone on the team felt that we were collectively fighting for something larger than ourselves.

As a producer I had high hopes for the film.

But I only really saw its potential and how far it could go when the community here in Missoula wrapped its arms around us and our film, and propelled us into the sky. Thank you, Big Sky, Rachel Gregg and Michael Workman.

We managed to craft a somewhat unique distribution path for it – from being a full commission for Witness-Al Jazeera English, to being acquired by Sheila Nevins to launch MTV Documentary Films.

We also showed up everywhere with Bruce at film festivals around the country to move forward the conversation on Black fatherhood, mental health, and gun violence.

It was the right moment, and a lot of luck.

That film ended up being nominated for an Academy Award. The journey to that moment will have to be a separate keynote someday.

The gist here is, You decide what your film looks like, what it speaks to, and when. As artists, we are inherently creatures of solitude. While I am here because of my community, I am also here because of the decisions I took myself, not listening to TV executives. Like me.

Finally, there are the films that are primed for streaming and are clearly going to be commercial hits.

And they can still be authentic to the filmmakers, to the community, and have the ability to excite large audiences.

We are taught to believe these are “lesser” documentaries because, Where are the “issues”?

I recently attended the premiere of my dear friend, the brilliant Smriti Mundhra’s hit Netflix documentary series The Romantics, an homage to Hindi film cinema.

Watching it with my Indian mother-in-law and the community, and hearing the thundering applause, hoots and cheers as their favorite movie stars came on screen, and them singing along to Hindi film classics was so profound for me. It was a brilliant example of how there’s space for all sorts of stories and communities in the commercial world.

We just have to push for it, even when gatekeepers are not yet ready. There is space for joy; our films need to create it.

TV executives, streamer leadership, commissioning bodies: these all change; what holds true and outlives all of them is the work we do, the stories we tell.

But some years are not joyful, more challenging than others for filmmakers in this space.

Last year, I left the grantmaking world to become a studio executive. Again, a whole other keynote here!

I am here now and it’s a great privilege to understand some of the inner workings of what it takes for projects to be commercially successful. As a gatekeeper I have an opportunity to potentially expand the space.

To work with new creatives and perspectives with a different kind of budget.

To learn from research and analysis, what is perceived as zeitgeisty, plus the tastes of those who greenlight projects. It forces me to either learn more or do better.

It pushes me to vouch for stories that entertain and engage a broad audience and still be true to myself and where I come from. To shift culture.

Personally I hope that all this, combined with the different nonfiction storytelling roles that I’ve held in the past two decades, the films I’ve made, the meaningful relationships I’ve formed with filmmakers and participants, will help me find my way.

It’s anyone’s guess what this year will hold. Where am I headed? I don’t know.

But I know I am going nowhere without these people who have pulled me in, held me, and pushed me – sometimes a little too hard – to show up, do better, and be better.

And so in closing, this is my message: Do what you’re doing and do it well. Don’t be confused and distracted by what others are doing, be open to possibilities, be ready to reorient your ambitions and grow differently.

And most importantly, carry each other.

TV executives, streamer leadership, commissioning bodies: these all change; what holds true and outlives all of them is the work we do, the stories we tell.

Let this be a year of unlearning and learning, so that in the arc of our own stories, we continue to rise.

I wish you all an artistically exciting, and fulfilling year ahead.

Thank you.